(Press-News.org) UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. -- Using an unusually well-preserved subfossil jawbone, a team of researchers -- led by Penn State and with a multi-national team of collaborators including scientists from the Université d'Antananarivo in Madagascar -- has sequenced for the first time the nuclear genome of the koala lemur (Megaladapis edwardsi), one of the largest of the 17 or so giant lemur species that went extinct on the island of Madagascar between about 500 and 2,000 years ago. The findings reveal new information about this animal's position on the primate family tree and how it interacted with its environment, which could help in understanding the impacts of past lemur extinctions on Madagascar's ecosystems.

"More than 100 species of lemurs live on Madagascar today, but in recent history, the diversity of these animals was even greater," said George Perry, associate professor of anthropology and biology, Penn State. "From skeletal remains and radiocarbon dating, we know that at least 17 species of lemurs have gone extinct, and that these extinctions happened relatively recently. What's fascinating is that all the extinct lemurs were bigger than the ones that survived, and some substantially so; for example, the one we studied weighed about 180 pounds."

Perry explained that much is unknown about the biology of these extinct lemurs and what their ecosystems were like. There is even uncertainty about how they were related to each other and to the extant lemurs that are alive today. This is due, in part, he said, to the difficulty inherent in working with ancient DNA, especially from animals that lived in tropical and sub-tropical locations.

"While many nuclear genomes of extinct animals have now been sequenced since the first extinct animal -- the woolly mammoth -- had its nuclear genome sequenced at Penn State in 2008, relatively few of these species have been from warmer climates due to faster DNA degradation in these conditions," said Perry. "For example, to date, Penn State's Ancient DNA Laboratory has screened hundreds of extinct lemur subfossils [or ancient bones that have not yet gone through the process of turning into rock]. Yet only two of our samples had sufficient DNA preservation for us to attempt to sequence the nuclear genome. The M. edwardsi jawbone was the best preserved."

Part of the collection of the Laboratory of Primatology and Paleontology at the University of Antananarivo, the jawbone that the team used in its study -- which was published today (June 22) in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences -- had originally been discovered at Beloha Anavoha in southern Madagascar. Carbon-14 dating, a commonly used method for determining the age of archeological artifacts of a biological origin, revealed that the M. edwardsi jawbone was about 1,475 years old.

The team used a fragment of the jawbone to sequence the nuclear genome of M. edwardsi. Nuclear DNA contains information about both parents, whereas mitochondrial DNA, which is also used to study extinct species, only contains information about the mother.

In addition to M. edwardsi, the team newly sequenced the genomes of two extant -- or currently living -- lemur species: the weasel sportive lemur (Lepilemur mustelinus) and the red-fronted lemur (Eulemur rufifrons). The DNA from these species came from ear punches that members of the team, led by Edward E. Louis Jr., director of conservation genetics at Omaha's Henry Doorly Zoo and Aquarium and general director of the Madagascar Biodiversity Partnership, obtained from wild-caught individuals.

"Previous studies based on skull and teeth comparisons suggested that M. edwardsi was closely related to L. mustelinus," said Stephanie Marciniak, postdoctoral scholar in anthropology, Penn State. "However, our genetic analyses revealed that M. edwardsi is more closely related to E. rufifrons."

According to Perry, the first genetic study of M. edwardsi -- conducted in 2005 by Anne Yoder, Braxton Craven Professor of Evolutionary Biology at Duke University and her team, and now a co-author of the current paper -- was an analysis of a small fragment of the species' mitochondrial DNA.

"When Anne and her team observed the phylogenetic placement of Megaladapis to be more closely related to Eulemur than to Lepilemur, it was somewhat of a shock, in a cool way," he said. "But uncertainty about the relationship between Megaladapis and other lemurs has continued to linger among scientists. That 2005 study was a really important one, and now with the more sophisticated technology available to us today, we robustly confirmed that major finding."

In addition to extant lemur species, the team also compared M. edwardsi's genome to the genomes of dozens of more distantly related species, including golden snub-nosed colobine monkeys, which are folivores, and horses, which are herbivores.

"We found similarities between M. edwardsi and these two species in some of the genes that encode protein products that function in the biodegradation of plant toxins and in nutrient absorption, consistent with dental evidence suggesting that M. edwardsi was folivorous," said Marciniak.

Specifically, the researchers identified similarities between M. edwardsi and the golden snub-nosed monkey across genes with hydrolase activity functions, and between M. edwardsi and horse across genes with brush border functions.

"Hydrolases help to break down plant secondary compounds, while brush border microvilli play crucial roles in nutrient absorption and chemical breakdown in the gut," said Marciniak.

In the future, the team plans to analyze DNA from additional extinct lemurs and non-lemur primates with the goal of continuing to fill in the gaps in the primate family tree.

"For now," said Perry, "we are excited to have been able to analyze M. edwardsi's nuclear genome sequence for insights into the evolutionary biology and behavioral ecology of this extinct animal and to have resolved its phylogenetic relationship with some other extant lemurs."

INFORMATION:

Other Penn State authors include Mehreen Mughal, graduate student in bioinformatics and genomics, and Richard Bankoff, graduate student in anthropology. Authors from Université d'Antananarivo include Heritiana Randrianatoandro, graduate student; Jeannot Randrianasy, head of the Laboratoire de Primatologie et Paléontologie des Vertébrés; and Brigitte Raharivololona, head of the Anthropobiologie et Développement Durable Mention. Other authors include Laurie Godfrey, professor emerita, University of Massachusetts, Amherst; Christina Bergey, assistant professor of molecular biosciences, Rutgers University; Brooke Crowley, associate professor of geology; Kathleen Muldoon, associate professor of anatomy, Midwestern University; Stephan Schuster, professor of biological sciences, Nanyang Technological University; Ripan Malhi, professor of anthropology, University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign; Edward Louis Jr., director of the Department of Conservation Genetics, Omaha Henry Doorly Zoo; and Logan Kistler, curator of archaeobotany and archaeogenetics, Smithsonian Institution.

The College of Liberal Arts and Huck Institutes of the Life Sciences at Penn State, the National Science Foundation and the Ahmanson Foundation supported this research.

To better understand the role of bacteria in health and disease, National Institutes of Health researchers fed fruit flies antibiotics and monitored the lifetime activity of hundreds of genes that scientists have traditionally thought control aging. To their surprise, the antibiotics not only extended the lives of the flies but also dramatically changed the activity of many of these genes. Their results suggested that only about 30% of the genes traditionally associated with aging set an animal's internal clock while the rest reflect the body's response to bacteria.

"For ...

COLUMBUS, Ohio - When the summer sun blazes on a hot city street, our first reaction is to flee to a shady spot protected by a building or tree.

A new study is the first to calculate exactly how much these shaded areas help lower the temperature and reduce the "urban heat island" effect.

Researchers created an intricate 3D digital model of a section of Columbus and determined what effect the shade of the buildings and trees in the area had on land surface temperatures over the course of one hour on one summer day.

"We can use the information from our model to formulate guidelines for community greening and tree planting efforts, and even where to locate buildings to maximize shading on other buildings and roadways," said Jean-Michel Guldmann, co-author of the study and ...

A new tool to help conserve one of the UK's most threatened mammals has been released today, with the publication of the first high-quality reference genome for the European water vole. The genome was generated by scientists at the Wellcome Sanger Institute, in collaboration with animal conservation charity the Wildwood Trust, as part of the Darwin Tree of Life Project.

The genome, published today (24 June 2021) through Wellcome Open Research, is openly available as a reference for researchers seeking to assess water vole population genetics, better understand how the species has evolved and to manage reintroduction efforts.

The European water vole (Arvicola ...

A team from Japan and the United States has identified the design principles for creating large "ideal" proteins from scratch, paving the way for the design of proteins with new biochemical functions.

Their results appear June 24, 2021, in Nature Communications.

The team had previously developed principles to design small versions of what they call "ideal proteins," which are structures without internal energetic frustration.

Such proteins are typically designed with a molecular feature called beta strands, which serve a key structural role for the molecules. In ...

Our planet's strongest ocean current, which circulates around Antarctica, plays a major role in determining the transport of heat, salt and nutrients in the ocean. An international research team led by the Alfred Wegener Institute has now evaluated sediment samples from the Drake Passage. Their findings: during the last interglacial period, the water flowed more rapidly than it does today. This could be a blueprint for the future and have global consequences. For example, the Southern Ocean's capacity to absorb CO2 could decrease, which would in turn intensify climate change. The study has now been published in the journal Nature Communications.

The Antarctic Circumpolar Current (ACC) is the world's strongest ocean ...

Indonesia's volcanoes are among the world's most dangerous. Why? Through chemical analyses of tiny minerals in lava from Bali and Java, researchers from Uppsala University and elsewhere have found new clues. They now understand better how the Earth's mantle is composed in that particular region and how the magma changes before an eruption. The study is published in Nature Communications.

Frances Deegan, the study's first author and a researcher at Uppsala University's Department of Earth Sciences, summarises the findings.

"Magma is formed in the mantle, and the composition of the mantle under Indonesia used to be only partly known. ...

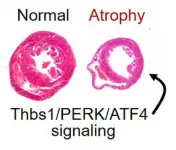

In many situations, heart muscle cells do not respond to external stresses in the same ways that skeletal muscle cells do. But under some conditions, heart and skeletal muscles can both waste away at fatally rapid rates, according to a new study led by experts at Cincinnati Children's.

The new findings, based on studies of mouse models, represent an important milestone in a long effort to prevent or even reverse cardiac atrophy, which can lead to fatal heart failure when the body loses large amounts of weight or experiences extended periods of weightlessness in space. Detailed findings were published online June 24, 2021, in Nature Communications.

"NASA is very interested in cardiac atrophy," says Jeffery Molkentin, PhD, Co-Director ...

UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO

TORONTO, ON - A new study from researchers at the University of Toronto found that 63% of Canadians with migraine headaches are able to flourish, despite the painful condition.

"This research provides a very hopeful message for individuals struggling with migraines, their families and health professionals," says lead author Esme Fuller-Thomson, who spent the last decade publishing on negative mental health outcomes associated with migraines, including suicide attempts, anxiety disorders and depression. "The findings of our study have contributed to a major paradigm shift for me. There are important lessons to be learned from those who are flourishing."

A migraine headache, which afflicts ...

A recent study finds states that exhibit higher levels of systemic racism also have pronounced racial disparities regarding access to health care. In short, the more racist a state was, the better access white people had - and the worse access Black people had.

"This study highlights the extent to which health care inequities are intertwined with other social inequities, such as employment and education," says Vanessa Volpe, corresponding author of the study and an assistant professor of psychology at North Carolina State University. "This helps explain why health inequities are so intractable. Tackling health care inequities will require us to address broader social systems that significantly benefit white people ...

"Red flag" gun laws--which allow law enforcement to temporarily remove firearms from a person at risk of harming themselves or others--are gaining attention at the state and federal levels, but are under scrutiny by legislators who deem them unconstitutional. A new analysis by legal scholars at NYU School of Global Public Health describes the state-by-state landscape for red flag legislation and how it may be an effective tool to reduce gun violence, while simultaneously protecting individuals' constitutional rights.

Gun violence is a significant public health problem in the U.S., with more than 38,000 people killed by firearms each year. Following several mass shootings this spring, President Biden urged ...