(Press-News.org) To better understand the role of bacteria in health and disease, National Institutes of Health researchers fed fruit flies antibiotics and monitored the lifetime activity of hundreds of genes that scientists have traditionally thought control aging. To their surprise, the antibiotics not only extended the lives of the flies but also dramatically changed the activity of many of these genes. Their results suggested that only about 30% of the genes traditionally associated with aging set an animal's internal clock while the rest reflect the body's response to bacteria.

"For decades scientists have been developing a hit list of common aging genes. These genes are thought to control the aging process throughout the animal kingdom, from worms to mice to humans," said Edward Giniger, Ph.D., senior investigator, at the NIH's National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) and the senior author of the study published in iScience. "We were shocked to find that only about 30% of these genes may be directly involved in the aging process. We hope that these results will help medical researchers better understand the forces that underlie several age-related disorders."

The results happened by accident. Dr. Giniger's team studies the genetics of aging in a type of fruit fly called Drosophila. Previously, the team showed how a hyperactive immune system may play a critical role in the neural damage that underlies several aging brain disorders. However, that study did not examine the role that bacteria may have in this process.

To test this idea, they raised newborn male flies on antibiotics to prevent bacteria growth. At first, they thought that the antibiotics would have little or no effect. But, when they looked at the results, they saw something interesting. The antibiotics lengthened the fly's lives by about six days, from 57 days for control flies to 63 for the treated ones.

"This is a big jump in age for flies. In humans, it would be the equivalent of gaining about 20 years of life," said Arvind Kumar Shukla, Ph.D., a post-doctoral fellow on Dr. Giniger's team and the lead author of the study. "We were totally caught off guard and it made us wonder why these flies took so long to die."

Dr. Shukla and his colleagues looked for clues in the genes of the flies. Specially, they used advanced genetic techniques to monitor gene activity in the heads of 10, 30, and 45-day old flies. In a previous study, the team discovered links between the age of a fly and the activity of several genes. In this study, they found that raising the flies on antibiotics broke many of these links.

Overall, the gene activity of the flies fed antibiotics changed very little with age. Regardless of their actual age, the treated flies genetically looked like 30-day old control flies. This appeared to be due to a flat line in the activity of about 70% of the genes the researchers surveyed, many of which are thought to control aging.

"At first, we had a hard time believing the results. Many of these genes are classical hallmarks of aging and yet our results suggested that their activity is more a function of the presence of bacteria rather than the aging process," said Dr. Shukla.

Notably, this included genes that control stress and immunity. The researchers tested the impact that the antibiotics had on these genes by starving some flies or infecting others with harmful bacteria and found no clear trend. At some ages, the antibiotics helped flies survive starvation or infection longer than normal whereas at other ages the drugs either had no effect or reduced the chances of survival.

Further experiments supported the results. For instance, the researchers saw similar results on gene activity when they prevented the growth of bacteria by raising the flies in a completely sterile environment without the antibiotics. They also saw a similar trend when they reanalyzed the data from another study that had raised flies on antibiotics. Again, the antibiotics severed many of the links between aging and hallmark gene activity.

Finally, the team found an explanation for why antibiotics extended the lives of flies in the remaining 30% of the genes they analyzed. In short, the rate at which the activity of these genes changed with age was slower than normal in flies that were fed antibiotics.

Interestingly, many of these genes are known to control sleep-wake cycles, the detection of odorants, and the maintenance of exoskeletons, or the crunchy shells that encase flies. Experiments on sleep-wake cycles supported the link between these genes and aging. The activity of awake flies decreased with age and this trend was enhanced by treating the flies with antibiotics.

"We found that there are some genes that are in fact setting the body's internal clock," said Dr. Giniger. "In the future, we plan to locate which genes are truly linked to the aging process. If we want to combat aging, then we need to know precisely which genes are setting the clock."

INFORMATION:

Article:

Shukla, A.K. et al., Common features of aging fail to occur in Drosophila raised without a

bacterial microbiome, iScience, June 24, 2021, DOI: 10.1016/j.isci.2021.102703

This study was supported by the NIH Intramural Research Program at the NINDS.

This press release describes a basic research finding. Basic research increases our understanding of human behavior and biology, which is foundational to advancing new and better ways to prevent, diagnose, and treat disease. Science is an unpredictable and incremental process-- each research advance builds on past discoveries, often in unexpected ways. Most clinical advances would not be possible without the knowledge of fundamental basic research. To learn more about basic research, visit https://www.nih.gov/news-events/basic-research-digital-media-kit.

NINDS is the nation's leading funder of research on the brain and nervous system. The mission of NINDS is to seek fundamental knowledge about the brain and nervous system and to use that knowledge to reduce the burden of neurological disease.

About the National Institutes of Health (NIH): NIH, the nation's medical research agency, includes 27 Institutes and Centers and is a component of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. NIH is the primary federal agency conducting and supporting basic, clinical, and translational medical research, and is investigating the causes, treatments, and cures for both common and rare diseases. For more information about NIH and its programs, visit http://www.nih.gov.

COLUMBUS, Ohio - When the summer sun blazes on a hot city street, our first reaction is to flee to a shady spot protected by a building or tree.

A new study is the first to calculate exactly how much these shaded areas help lower the temperature and reduce the "urban heat island" effect.

Researchers created an intricate 3D digital model of a section of Columbus and determined what effect the shade of the buildings and trees in the area had on land surface temperatures over the course of one hour on one summer day.

"We can use the information from our model to formulate guidelines for community greening and tree planting efforts, and even where to locate buildings to maximize shading on other buildings and roadways," said Jean-Michel Guldmann, co-author of the study and ...

A new tool to help conserve one of the UK's most threatened mammals has been released today, with the publication of the first high-quality reference genome for the European water vole. The genome was generated by scientists at the Wellcome Sanger Institute, in collaboration with animal conservation charity the Wildwood Trust, as part of the Darwin Tree of Life Project.

The genome, published today (24 June 2021) through Wellcome Open Research, is openly available as a reference for researchers seeking to assess water vole population genetics, better understand how the species has evolved and to manage reintroduction efforts.

The European water vole (Arvicola ...

A team from Japan and the United States has identified the design principles for creating large "ideal" proteins from scratch, paving the way for the design of proteins with new biochemical functions.

Their results appear June 24, 2021, in Nature Communications.

The team had previously developed principles to design small versions of what they call "ideal proteins," which are structures without internal energetic frustration.

Such proteins are typically designed with a molecular feature called beta strands, which serve a key structural role for the molecules. In ...

Our planet's strongest ocean current, which circulates around Antarctica, plays a major role in determining the transport of heat, salt and nutrients in the ocean. An international research team led by the Alfred Wegener Institute has now evaluated sediment samples from the Drake Passage. Their findings: during the last interglacial period, the water flowed more rapidly than it does today. This could be a blueprint for the future and have global consequences. For example, the Southern Ocean's capacity to absorb CO2 could decrease, which would in turn intensify climate change. The study has now been published in the journal Nature Communications.

The Antarctic Circumpolar Current (ACC) is the world's strongest ocean ...

Indonesia's volcanoes are among the world's most dangerous. Why? Through chemical analyses of tiny minerals in lava from Bali and Java, researchers from Uppsala University and elsewhere have found new clues. They now understand better how the Earth's mantle is composed in that particular region and how the magma changes before an eruption. The study is published in Nature Communications.

Frances Deegan, the study's first author and a researcher at Uppsala University's Department of Earth Sciences, summarises the findings.

"Magma is formed in the mantle, and the composition of the mantle under Indonesia used to be only partly known. ...

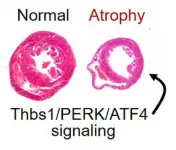

In many situations, heart muscle cells do not respond to external stresses in the same ways that skeletal muscle cells do. But under some conditions, heart and skeletal muscles can both waste away at fatally rapid rates, according to a new study led by experts at Cincinnati Children's.

The new findings, based on studies of mouse models, represent an important milestone in a long effort to prevent or even reverse cardiac atrophy, which can lead to fatal heart failure when the body loses large amounts of weight or experiences extended periods of weightlessness in space. Detailed findings were published online June 24, 2021, in Nature Communications.

"NASA is very interested in cardiac atrophy," says Jeffery Molkentin, PhD, Co-Director ...

UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO

TORONTO, ON - A new study from researchers at the University of Toronto found that 63% of Canadians with migraine headaches are able to flourish, despite the painful condition.

"This research provides a very hopeful message for individuals struggling with migraines, their families and health professionals," says lead author Esme Fuller-Thomson, who spent the last decade publishing on negative mental health outcomes associated with migraines, including suicide attempts, anxiety disorders and depression. "The findings of our study have contributed to a major paradigm shift for me. There are important lessons to be learned from those who are flourishing."

A migraine headache, which afflicts ...

A recent study finds states that exhibit higher levels of systemic racism also have pronounced racial disparities regarding access to health care. In short, the more racist a state was, the better access white people had - and the worse access Black people had.

"This study highlights the extent to which health care inequities are intertwined with other social inequities, such as employment and education," says Vanessa Volpe, corresponding author of the study and an assistant professor of psychology at North Carolina State University. "This helps explain why health inequities are so intractable. Tackling health care inequities will require us to address broader social systems that significantly benefit white people ...

"Red flag" gun laws--which allow law enforcement to temporarily remove firearms from a person at risk of harming themselves or others--are gaining attention at the state and federal levels, but are under scrutiny by legislators who deem them unconstitutional. A new analysis by legal scholars at NYU School of Global Public Health describes the state-by-state landscape for red flag legislation and how it may be an effective tool to reduce gun violence, while simultaneously protecting individuals' constitutional rights.

Gun violence is a significant public health problem in the U.S., with more than 38,000 people killed by firearms each year. Following several mass shootings this spring, President Biden urged ...

WHO Frank A. J. L. Scheer, PhD, MSc, Neuroscientist and Marta Garaulet, PhD, Visiting Scientist, both of the Division of Sleep and Circadian Disorders, Departments of Medicine and Neurology, Brigham and Women's Hospital. Drs. Scheer and Garaulet are co-corresponding authors of a new paper published in The FASEB Journal.

WHAT Eating milk chocolate every day may sound like a recipe for weight gain, but a new study of postmenopausal women has found that eating a concentrated amount of chocolate during a narrow window of time in the morning may help the body burn fat and decrease blood sugar levels.

To find out about the effects of eating milk chocolate at different times of day, researchers from the Brigham collaborated ...