New fossil discovery from Israel points to complicated evolutionary process

2021-06-24

(Press-News.org) BINGHAMTON, N.Y. -- Analysis of recently discovered fossils found in Israel suggest that interactions between different human species were more complex than previously believed, according to a team of researchers including Binghamton University anthropology professor Rolf Quam.

The research team, led by Israel Hershkovitz from Tel Aviv University, published their findings in Science, describing recently discovered fossils from the site of Nesher Ramla in Israel. The Nesher Ramla site dates to about 120,000-140,000 years ago, towards the very end of the Middle Pleistocene time period.

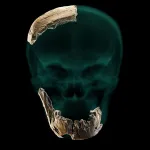

The human fossils were found by Dr. Zaidner of the Hebrew University during salvage excavations at the Nesher Ramla prehistoric site, near the city of Ramla. Digging down about 8 meters, the excavators found large quantities of animal bones, including horses, fallow deer and aurochs, as well as stone tools and human bones. The human fossils consist of a partial cranial vault and a mandible. Researchers made virtual reconstructions of the fossils to analyze them using sophisticated computer software programs and to compare them with other fossils from Europe, Africa and Asia. The results suggest that the Nesher Ramla fossils represent late survivors of a population of humans who lived in the Middle East during the Middle Pleistocene period.

"The oldest fossils that show Neandertal features are found in Wesern Europe, so researchers generally believe the Neandertals originated there," said Quam. "However, migrations of different species from the Middle East into Europe may have provided genetic contributions to the Neandertal gene pool during the course of their evolution."

The finds from Nesher Ramla are noteworthy because they sample a time period in the Middle East with few fossils, so they are important additions to the growing fossil record from the region. Other fossils from this approximate time period are difficult to classify taxonomically since they seem to show a combination of features seen in both Neandertals and modern humans. The Nesher Ramla fossils seem more Neandertal-like in the mandible and less Neandertal-like in the cranial vault, but are clearly distinct from modern humans. This pattern matches what has been suggested for both Neandertals and modern humans, where the diagnostic skeletal features of each species appear first in the facial region and later on the cranial vault.

Describing the significance of the find, Dr. Hershkovitz said: "It enables us to make new sense of previously found human fossils, add another piece to the puzzle of human evolution, and understand the migrations of humans in the old world. Even though they lived so long ago, in the late middle Pleistocene, the Nesher Ramla people can tell us a fascinating tale, revealing a great deal about their descendants' evolution and way of life."

The researchers were careful not to attribute the Nesher Ramla fossils to a new species. Rather, they grouped them together with earlier fossils from several sites in the Middle East that have been difficult to classify and considered all of them to represent a local population of humans that occupied the region between about 420,000-120,000. Given the fact that the Middle East sits at the crossroads of three continents, it is likely that different human groups moved into and out of the region regularly, exchanging genes with the local inhabitants. This scenario might explain the variable anatomical features in these fossils, with the Nesher Ramla fossils representing the latest known survivors of this localized Middle Pleistocene population.

"This is a complicated story, but what we are learning is that the interactions between different human species in the past were much more convoluted than we had previously appreciated," said Quam.

INFORMATION:

The study, "A Middle Pleistocene Homo from Nesher Ramla, Israel," was published in Science, along with a companion paper discussing the culture, way of life, and behavior of the Nesher Ramla Homo.

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-06-24

Researchers at Tufts University, University College London (UCL), Cambridge University and University of California at Santa Barbara have demonstrated that a catalyst can indeed be an agent of change. In a study published today in Science, they used quantum chemical simulations run on supercomputers to predict a new catalyst architecture as well as its interactions with certain chemicals, and demonstrated in practice its ability to produce propylene - currently in short supply - which is critically needed in the manufacture of plastics, fabrics and other chemicals. The improvements have potential for highly efficient, "greener" chemistry with a lower carbon footprint.

The demand for propylene is ...

2021-06-24

The discovery of a new Homo group in this region, which resembles Pre-Neanderthal populations in Europe, challenges the prevailing hypothesis that Neanderthals originated from Europe, suggesting that at least some of the Neanderthals' ancestors actually came from the Levant.

The new finding suggests that two types of Homo groups lived side by side in the Levant for more than 100,000 years (200-100,000 years ago), sharing knowledge and tool technologies: the Nesher Ramla people who lived in the region from around 400,000 years ago, and the Homo sapiens who arrived later, some 200,000 years ago.

The new discovery also gives clues about a mystery in human evolution: How did genes of Homo sapiens penetrate the Neanderthal population that had presumably lived in Europe long before ...

2021-06-24

Mythological nymphs reincarnate as a group of corn smut proteins to launch a battle on maize immunity. One of these proteins appears to stand out among its sister Pleiades, much like its namesake character in Greek mythology. The research carried out at GMI - Gregor Mendel Institute of Molecular Plant Biology of the Austrian Academy of Sciences - is published in the journal PLOS Pathogens.

Pathogenic organisms exist under various forms and use diverse strategies to survive and multiply at the expense of their hosts. Some of these pathogens are termed "biotrophic", as they are parasites that maintain their hosts alive. These biotrophic pathogens deregulate physiological processes in their hosts by suppressing their immune defenses and favoring disease development. ...

2021-06-24

INDIANAPOLIS -- A first-of-its-kind large-scale study of vegetation growth in the Northern Hemisphere over the past 30 years has found that vegetation is becoming increasingly water-limited as global temperatures increase.

The results are significant since vegetation is one of the biggest factors when it comes to controlling water and carbon cycling across Earth, which influences global temperatures. The work by IUPUI and Indiana University Bloomington researchers Wenzhe Jiao, END ...

2021-06-24

(Denver)-Patients with primary lung cancer detected using low-dose computed tomography screening are at reduced risk of developing brain metastases after diagnosis, according to a study published in the Journal of Thoracic Oncology.

JTO is an official journal of the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer. The full study is available here: Impact of Low-Dose Computed Tomography Screening for Primary Lung Cancer on Subsequent Risk of Brain Metastasis - Journal of Thoracic Oncology (jto.org)

The researchers, led by Summer Han, PhD, from Stanford University School of Medicine in Palo ...

2021-06-24

A new research paper published in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition last week showed that a low Omega-3 Index is just as powerful in predicting early death as smoking. This landmark finding is rooted in data pulled and analyzed from the Framingham study, one of the longest running studies in the world.

The Framingham Heart Study provided unique insights into cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk factors and led to the development of the Framingham Risk Score based on eight baseline standard risk factors--age, sex, smoking, hypertension treatment, diabetes status, systolic blood pressure, total cholesterol (TC), and HDL cholesterol.

CVD is still the leading cause of death globally, and risk can be reduced by changing behavioral factors such as unhealthy diet, ...

2021-06-24

A new technique to look at tumors under the microscope has revealed the cellular make-up of Wilm's tumors, a childhood kidney cancer, in unprecedented detail. This new approach could help understand how tumors develop and grow, and fuel research into new treatments for children's cancers.

Scientists at the Princess Máxima Center for pediatric oncology developed a new imaging technique and computational pipeline to study millions of cells in 3D tissue, revealing hundreds of features from each individual cell. Their research was published this month in Nature Biotechnology.

By offering a look at individual cells within an intact organ, the new technique helps scientists analyze the molecular profile of the cells, as well as their ...

2021-06-24

DURHAM, N.C. - The brain's neurons tend to get most of the scientific attention, but a set of cells around them called astrocytes - literally, star-shaped cells - are increasingly being viewed as crucial players in guiding a brain to become properly organized.

Specifically, astrocytes, which form about half the mass of a human brain, seem to guide the formation of synapses, the connections between neurons that are formed and remodeled as we learn and remember.

A new study from Duke and UNC scientists has discovered a crucial protein involved in the communication and coordination between astrocytes as they build synapses. Lacking this molecule, called hepaCAM, astrocytes aren't as sticky as they ...

2021-06-24

GRAND RAPIDS, Mich. (June 24, 2021) -- The same taste-sensing molecule that helps you enjoy a meal from your favorite restaurant may one day lead to improved ways to treat diabetes and other metabolic and immune diseases.

TRPM5 is a specialized protein that is concentrated in the taste buds, where it helps relay messages to and from cells. It has long been of interest to researchers due to its roles in taste perception and blood sugar regulation.

Now, a team led by scientists at Van Andel Institute has published the first-ever high-resolution images of TRPM5, which reveal two areas that may serve as targets for new medications. The structures also may aid in the development of low-calorie alternative sweeteners that mimic sugar. The findings were published today in Nature ...

2021-06-24

BELLINGHAM, Washington, USA - The open access Journal of Astronomical Telescopes, Instruments, and Systems (JATIS) has published END ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] New fossil discovery from Israel points to complicated evolutionary process