INFORMATION:

This study was conducted by an international consortium comprised of scientists at NCI and the Children's Oncology Group in the United States, and the Children's Cancer and Leukaemia Group and the National Cancer Research Institute's Young Onset Soft Tissue Sarcoma Subgroup in the United Kingdom. The data are available at clinomics.ccr.cancer.gov/clinomics/public. The research was supported by NCI and St. Baldrick's Foundation in Monrovia, California.

About the National Cancer Institute (NCI): NCI leads the National Cancer Program and NIH's efforts to dramatically reduce the prevalence of cancer and improve the lives of cancer patients and their families, through research into prevention and cancer biology, the development of new interventions, and the training and mentoring of new researchers. For more information about cancer, please visit the NCI website at cancer.gov or call NCI's contact center, the Cancer Information Service, at 1-800-4-CANCER (1-800-422-6237).

About the National Institutes of Health (NIH): NIH, the nation's medical research agency, includes 27 Institutes and Centers and is a component of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. NIH is the primary federal agency conducting and supporting basic, clinical, and translational medical research, and is investigating the causes, treatments, and cures for both common and rare diseases. For more information about NIH and its programs, visit nih.gov.

International study of rare childhood cancer finds genetic clues, potential for tailored therapy

2021-06-24

(Press-News.org) In children with rhabdomyosarcoma, or RMS, a rare cancer that affects the muscles and other soft tissues, the presence of mutations in several genes, including TP53, MYOD1, and CDKN2A, appear to be associated with a more aggressive form of the disease and a poorer chance of survival. This finding is from the largest-ever international study on RMS, led by scientists at the National Cancer Institute's (NCI) Center for Cancer Research, part of the National Institutes of Health.

The study, published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology on June 24, provides an unprecedented look at data for a large cohort of patients with RMS, offering genetic clues that could lead to more widespread use of tumor genetic testing to predict how individual patients with this childhood cancer will respond to therapy, as well as to the development of targeted treatments for the disease.

"These discoveries change what we do with these patients and trigger a lot of really important research into developing new therapies that target these mutations," said Javed Khan, M.D., of NCI's Genetics Branch, who led the study.

"The standard therapy for RMS is almost a year of chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and surgery. These children get a lot of toxic treatments," said the study's first author, Jack Shern, M.D., of NCI's Pediatric Oncology Branch. "If we could predict who's going to do well and who's not, then we can really start to tailor our therapies or eliminate therapies that aren't going to be effective in a particular patient. And for the children that aren't going to do well, this allows us to think about new ways to treat them."

RMS is the most common type of soft tissue sarcoma in children. In patients whose cancer has remained localized, meaning that it has not spread, combination chemotherapies have led to a five-year survival rate of 70%-80%. But in patients whose cancer has spread or come back after treatment, the five-year survival rate remains poor at less than 30%, even with aggressive treatment.

Doctors have typically used clinical features, such as the location of the tumor in the body, as well as its size and to what extent it has spread, to predict how patients will respond to treatment, but this approach is imprecise. More recently, scientists have discovered that the presence of the PAX-FOXO1 fusion gene that is found in some patients with RMS is associated with poorer survival. Patients are now being screened for this genetic risk factor to help determine how aggressive their treatment should be.

Scientists have also begun using genetic analysis to dig more deeply into the molecular workings of RMS in search of other genetic markers of poorer survival. In this new study -- the largest genomic profiling effort of RMS tumors to date -- scientists from NCI and the Institute for Cancer Research in the United Kingdom analyzed DNA from tumor samples from 641 children with RMS enrolled over a two-decade period in several clinical trials. Scientists searched for genetic mutations and other aberrations in genes previously associated with RMS and linked that information with clinical outcomes. Among the patterns that emerged, patients with mutations in the tumor suppressor genes TP53, MYOD1, or CDKN2A had a poorer prognosis than patients without those mutations.

Using next-generation sequencing, researchers found a median of one mutation per tumor. Patients with two or more mutations per tumor had even poorer survival outcomes. In patients without the PAX-FOXO1 fusion gene, more than 50% had mutations in the RAS pathway genes, although RAS mutations did not appear to be associated with survival outcomes in this study.

The researchers believe that although they have identified the major mutations that may drive RMS development or provide information about prognosis, they have only scratched the surface in defining the genetics of this cancer, with many more mutations yet to be discovered. They note that more work is needed to identify targeted drugs for those mutations, and future clinical trials could incorporate genetic markers to more accurately classify patients into treatment groups. Two NCI-sponsored Children's Oncology Group clinical trials are currently being developed using these markers, and all participants will have their tumors molecularly profiled.

The researchers hope that routine tumor genetic testing for rare cancers, such as RMS, will soon be a standard part of the treatment plan, as it is for more common cancers, such as breast cancer.

"Genetic testing is going to become the standard of care," said Dr. Shern. "Instead of just the pathologists looking at these tumors, we're now going to have molecular profiling, and that's a leap forward."

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Genetic discovery could help guide treatment for aggressive childhood cancer

2021-06-24

A new study could lead to improved decision making in assigning treatments for children with the aggressive cancer rhabdomyosarcoma after revealing key genetic changes underlying development of the disease.

In the largest and most comprehensive study of rhabdomyosarcoma to date, scientists found that specific genetic changes in tumours are linked to aggressiveness, early age of onset and location in the body.

All these factors affect the chances that children will survive their disease - and understanding how they are driven by a cancer's genetics could lead to new ways of tailoring treatment for each patient.

Rhabdomyosarcoma is a rare type of cancer that resembles muscle tissue and mostly affects ...

Artificial intelligence breakthrough gives longer advance warning of ozone issues

2021-06-24

Ozone levels in the earth's troposphere (the lowest level of our atmosphere) can now be forecasted with accuracy up to two weeks in advance, a remarkable improvement over current systems that can accurately predict ozone levels only three days ahead. The new artificial intelligence system developed in the University of Houston's Air Quality Forecasting and Modeling Lab could lead to improved ways to control high ozone problems and even contribute to solutions for climate change issues.

"This was very challenging. Nobody had done this previously. I believe we are the first to try to forecast surface ...

Recycling next-generation solar panels fosters green planet

2021-06-24

ITHACA, N.Y. - Tossing worn-out solar panels into landfills may soon become electronics waste history.

Designing a recycling strategy for a new, forthcoming generation of photovoltaic solar cells - made from metal halide perovskites, a family of crystalline materials with structures like the natural mineral calcium titanate - will add a stronger dose of environmental friendliness to a green industry, according to Cornell University-led research published June 24 in Nature Sustainability.

The paper shows substantial benefits to recycling perovskite solar panels, though ...

Mosquito love songs send mixed message about immunity

2021-06-24

ITHACA, N.Y. - As mosquito-borne diseases pose risks for half the world's population, scientists have been releasing sterile or genetically modified male mosquitos in attempts to suppress populations or alter their traits to control human disease.

But these technologies have failed to spread very rapidly because they require successful mating of modified mosquitoes with mosquitoes in nature and not enough research exists to fully explain which male traits females seek when they choose a mate.

Now, a new Cornell study of Aedes aegypti mosquitoes investigates how a mating cue called "harmonic convergence" might affect immunity against parasites, bacteria and dengue virus in offspring, which has important ...

Quantum dots keep atoms spaced to boost catalysis

2021-06-24

HOUSTON - (June 24, 2021) - Hold on there, graphene. Seriously, your grip could help make better catalysts.

Rice University engineers have assembled what they say may transform chemical catalysis by greatly increasing the number of transition-metal single atoms that can be placed into a carbon carrier.

The technique uses graphene quantum dots (GQD), 3-5-nanometer particles of the super-strong 2D carbon material, as anchoring supports. These facilitate high-density transition-metal single atoms with enough space between the atoms to avoid clumping.

An international team led by chemical and biomolecular engineer Haotian Wang of Rice's Brown School of ...

Optical superoscillation without side waves

2021-06-24

Optical superoscillation refers to a wave packet that can oscillate locally in a frequency exceeding its highest Fourier component. This intriguing phenomenon enables production of extremely localized waves that can break the optical diffraction barrier. Indeed, superoscillation has proven to be an effective technique for overcoming the diffraction barrier in optical superresolution imaging. The trouble is that strong side lobes accompany the main lobes of superoscillatory waves, which limits the field of view and hinders application.

There also are tradeoffs between the main lobes and the side lobes of superoscillatory wave packets: reducing the superoscillatory feature size of the ...

Virus that causes COVID-19 can find alternate route to infect cells

2021-06-24

Early in the COVID-19 pandemic, scientists identified how SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, gets inside cells to cause infection. All current COVID-19 vaccines and antibody-based therapeutics were designed to disrupt this route into cells, which requires a receptor called ACE2.

Now, researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have found that a single mutation gives SARS-CoV-2 the ability to enter cells through another route - one that does not require ACE2. The ability to use an alternative entry pathway opens up the possibility of evading COVID-19 antibodies or vaccines, but the researchers did not find evidence of such evasion. However, the discovery does show that the ...

City of Hope researchers ID how most common breast cancer becomes resistant to treatment

2021-06-24

DUARTE, Calif. -- City of Hope, a world-renowned cancer research and treatment center, has identified how cancer cells in patients with early-stage breast cancer change and become resistant to hormone or combination therapies, according to a END ...

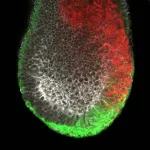

Gastrulation research reveals novel details about embryonic development

2021-06-24

Scientists from Helmholtz Zentrum München revise the current textbook knowledge about gastrulation, the formation of the basic body plan during embryonic development. Their study in mice has implications for cell replacement strategies and cancer research.

Gastrulation is the formation of the three principal germ layers - endoderm, mesoderm and ectoderm. Understanding the formation of the basic body plan is not only important to reveal how the fertilized egg gives rise to an adult organism, but also how congenital diseases arise. In addition, gastrulation serves as the basis to understand processes during embryonic development called epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition which is known to lead to cancer metastasis in adulthood ...

UConn researchers find health benefits of connecticut-grown sugar kelp

2021-06-24

When most Americans think of seaweed, they probably conjure images of a slimy plant they encounter at the beach. But seaweed can be a nutritious food too. A pair of UConn researchers recently discovered Connecticut-grown sugar kelp may help prevent weight gain and the onset of conditions associated with obesity.

In a paper published in the Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry by College of Agriculture, Health, and Natural Resources faculty Young-Ki Park, assistant research professor in the Department of Nutritional Sciences, and Ji-Young Lee, professor and head of the Department of Nutritional Sciences, the researchers reported significant findings supporting the nutritional benefits of Connecticut-grown sugar kelp. They found brown sugar kelp (Saccharina latissima) ...