(Press-News.org) Under a concrete drainage culvert at the edge of a town in Botswana, a troop of banded mongoose is getting ready to leave its den. Moving from shade into light, the cat-sized animals scan the area for signs of danger and for opportunities to find something to eat in an increasingly crowded neighborhood.

Unbeknownst to them, the genetics of this troop's members -- and others like them -- are providing researchers in the College of Natural Resources and Environment with new understandings of how and why animal behavior changes in proximity to human development and how that change can impact infectious disease spread.

The researchers used genetic tools to identify changes in movement behavior among mongooses living in urban centers and natural areas, gaining important insights into how to better model disease transmission among wild animals living across complex landscapes. Results of their study, which was funded by a grant from the National Science Foundation's Ecology and Evolution of Infectious Diseases program, have been published in the journal Ecology and Evolution.

"The question has always been how do we predict what's going to happen once an infectious disease emerges," said Kathleen Alexander, the William E. Lavery Professor in the Department of Fish and Wildlife Conservation. "By using systems that are tractable, we can begin to learn a lot more about how disease dynamics are shaped by host behavior and environmental drivers, including urbanizing landscapes."

One tractable system can be found with social groups of banded mongooses, also known as troops, that live across urban and natural areas in Botswana. Over the past 20 years, researchers from the Chobe Research Institute and CARACAL, a nonprofit organization co-founded by Alexander, have been observing the behaviors of mongoose troops in the natural environment of Chobe National Park and in increasingly urban centers, such as Kasane.

Botswana's banded mongooses are ideal study subjects because they live in territorial social groups across the landscape, and, in northern Botswana, are infected with a novel tuberculosis pathogen closely related to human tuberculosis.

"We're looking for dispersal behaviors and movement of mongooses that may allow disease transmission to occur between these mongoose troops," said Professor Eric Hallerman, who specializes in population genetics and is a co-author of the paper. "This species tends to live in troop structures that are resistant to immigration from other troops, so it's important to know how they are moving across the landscape and interacting."

"They're a difficult species to follow on the ground because they look so similar, unlike, for example, cheetahs, which can be individually identified by their spots," continued Hallerman, who, along with Alexander, is an affiliate of Virginia Tech's Fralin Life Sciences Institute. "You can put ear tags and other markers on them, but they often lose the marks, making it difficult to track individuals across troops. Genetic approaches provide the key to addressing these difficulties."

To do so, the researchers needed samples. "We decided that the best option for trying to capture the most genetic diversity from the troops was to collect fresh stool samples," said Kelton Verble, the paper's lead author, who completed his master's degree in fisheries and wildlife sciences at Virginia Tech in 2018. He refined sample collection processes, tracking mongooses across landscape types and collecting fecal samples from a wide variety of troops.

"We also looked at the health status of the mongooses that moved between study troops," he said. "Our previous data indicated that tuberculosis-infected animals tended not to disperse, and data from this study supports this original finding."

Genetic data obtained from microsatellite DNA markers within the genome sequence of each animal allowed Verble to not only identify individuals that had moved between troops in their lifetime, but also characterize the general genetic makeup of the various troops across the landscape -- how were individuals connected and how would this influence disease transmission potential?

"With this study, we really wanted to explicitly investigate dispersal and clarify what was happening between and among troops across land type," said Alexander, who is also an affiliate of the Fralin Life Sciences Institute's new Center for Emerging, Zoonotic, and Arthropod-Borne Pathogens. "What we saw was that these urban landscapes were not only changing foraging behaviors, aggression, and den use, but also dispersal behaviors and, consequently, disease transmission potential."

The researchers discovered that mongooses living in urban landscapes were more likely to disperse to other troops in this land type, thereby increasing the chance of tuberculosis transmission. With more abundant, human-associated food sources, troops nearer to the city were also more likely to share dens and have overlapping home ranges.

"The banded mongoose is typically regarded as a philopatric species, meaning that if they're born to a troop, they stay there for life," said Verble, who is now working on a doctorate in genomics at the University of Alabama. "What we learned is that there was a lot more swapping of individuals between troops than had been recognized, which is crucial for predicting disease spread."

Such findings have implications not only for disease transmission among animals but also for understanding how zoonotic diseases, such as COVID-19, transfer from animals to humans and how urbanization might impact that spread.

"We've never been very good at predicting disease-emergence events," Alexander said. "We don't know when a pathogen will emerge, and we have trouble predicting what will happen when it does because there are so many possible influences. For zoonotic pathogens, it will be increasingly important to understand how animals interact with and are influenced by transforming landscapes and growing urban centers, information critical to advancing our toolkit for tackling public and animal health challenges."

INFORMATION:

Written by David Fleming

An immunotherapy based on supercharging the immune system's natural killer cells has been effective in treating patients with recurrent leukemia and other difficult to treat blood cancers. Now, researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have shown in preclinical studies conducted in mice and human cells that this type of cell-based immunotherapy also could be effective against solid tumors, starting with melanoma, a type of skin cancer that can be deadly if not caught early.

The study is published June 29 in Clinical Cancer Research, ...

[BRIDGEWATER, NJ; June 29, 2021] The American Association of Feline Practitioners (AAFP) has released the updated 2021 AAFP Feline Senior Care Guidelines to be published in the July issue of the Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery. This update provides emerging advances in feline medicine with respect to the aging cat. The Task Force of experts provides a thorough current review in feline medicine that emphasizes the individual senior patient.

As defined in the 2021 AAHA/AAFP Feline Life Stage Guidelines, cats over 10 years of age are considered to be 'senior.' Understanding the changing needs of each individual senior cat is critical for both veterinary professionals and cat owners. "Veterinary professionals are encouraged to use the 2021 ...

Osaka, Japan - A team of scientists led by the Department of Applied Physics at Osaka University, the Department of Physics and Electronics at Osaka Prefecture University, and the Department of Materials Chemistry at Nagoya University used photoinduced force microscopy to map out the forces acting on quantum dots in three dimensions. By eliminating sources of noise, the team was able to achieve subnanometer precision for the first time ever, which may lead to new advances in photocatalysts and optical tweezers.

Force fields are not the invisible barriers of science fiction but are a set of vectors indicating the magnitude and direction of forces acting in a region ...

Overview

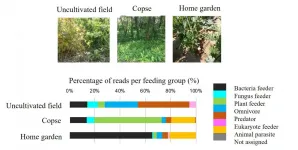

The research team of Professor Toshihiko Eki of the Department of Applied Chemistry and Life Science (and Research Center for Agrotechnology and Biotechnology), Toyohashi University of Technology used a next-generation sequencer to develop a highly efficient method to analyze soil nematodes by using the 18S ribosomal RNA gene regions as DNA barcodes. They successfully used this method to reveal characteristics of nematode communities that inhabit fields, copses, and home gardens. In the future, the target will be expanded to cover all soil-dwelling organisms in agricultural soils, etc., to allow investigations into a soil's environment and bio-diversity. This is expected to contribute to advanced agriculture.

Details

Similar to when the ...

Receiving a simple thank you, spending time with peers and further developing their expertise, are all factors that make veterinarians feel good at work, according to a new study by researchers at the University of Adelaide.

In the study published by Vet Record, researchers investigated the positive side of veterinary work and specifically what brings vets pleasure in their job.

Lead author Madeleine Clise, a psychologist and Adjunct Lecturer at the University of Adelaide's School of Psychology says: "At a time in Australia when there are national shortages of vets, particularly in regional areas, and increased publicity about the ...

Prolonged exposure to antibiotics leads to the gain of bacteria's ability to defeat the drugs designed to fight them. Thus, if such antibiotic-resistant bacteria cause the infection, the only chance to use a specialized virus called phage infecting specific bacteria species. It is a powerful weapon against deadly diseases. At the same time, the effective treatment depends on factors that would not be suspected for years to impact the successful therapy. Recently, researchers from the Institute of Physical Chemistry, Polish Academy of Sciences led by dr. Jan Paczesny and Professor ...

Tsukuba, Japan - Depression is a worldwide problem, with serious consequences for individual health and the economy, and rapid and effective screening tools are thus urgently needed to counteract its increasing prevalence. Now, researchers from Japan have found that artificial intelligence (AI) can be used to detect signs of depression.

In a study published this month in BMJ Open, researchers from University of Tsukuba have revealed that an AI system using machine learning could predict psychological distress among workers, which is a risk factor for depression. ...

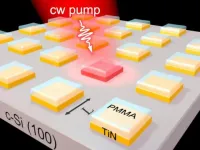

Atomic nuclei contain enormous energy that can be extracted through their fission mechanism, for example, as a result of the radioactive decay of uranium or plutonium nuclei. Likewise, a quantum of light of several electron-volts (2.4 eV in a laser pointer with a green beam) has colossal energy. If all photons were absorbed by matter, then its temperature could reach several thousand degrees. However, in practice this does not happen. The reason is the weak light-matter interaction due to the fact that the wavelength of light (500 nm) is a thousand times larger than the size of an emitting / absorbing atom (0.5 nm). It is this physical mechanism that prevents the destruction of matter when illuminated. The efficiency of light absorption increases ...

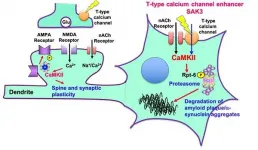

Researchers have identified a new treatment candidate that appears to not only halt neurodegenerative symptoms in mouse models of dementia and Alzheimer's disease, but also reverse the effects of the disorders.

The team, based at Tohoku University, published their results on June 8 in the International Journal of Molecular Sciences. The treatment candidate has been declared safe by Japan's governing board, and the researchers plan to begin clinical trials in humans in the next year.

"There are currently no disease-modifying therapeutics for neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer's disease, Lewy body dementia, Huntington ...

As our society and transportation systems become increasingly electrified, scientists worldwide are seeking more efficient and higher capacity storage systems. Researchers at KAUST have made an important contribution by modifying lithium-sulfur (Li-S) batteries to suppress a problem known as polysulfide shuttling.

"The bottleneck in the utilization of renewable energy, especially in transportation, is the need for high-density batteries," says Eman Alhajji, Ph.D. student and first author of the research paper.

Li-S batteries have several potential advantages over ...