Unlocking the power of the microbiome

2021-07-01

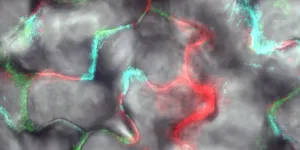

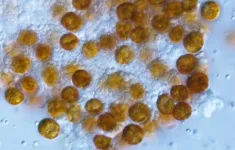

(Press-News.org) Hundreds of different bacterial species live in and on leaves and roots of plants. A research team led by Julia Vorholt from the Institute of Microbiology at ETH Zurich, together with colleagues in Germany, first inventoried and categorised these bacteria six years ago. Back then, they isolated 224 strains from the various bacterial groups that live on the leaves of thale cress (Arabidopsis thaliana). These can be assembled into simplified, or "synthetic" plant microbiomes. The researchers thus laid the foundations for their two new studies, which were just published in the journals Nature Plants and Nature Microbiology.

Volume control of the plant response

In the first study, the researchers investigated how plants respond to their colonisation by microorganisms. Vorholt's team dripped bacterial cultures onto the leaves of plants that had, up to that point, been cultivated under sterile conditions. As expected, different types of bacteria triggered a variety of responses in the plants. For example, exposure to certain genera of Gammaproteobacteria caused the thale cress plants to activate a total of more than 3,000 different genes, while those of Alphaproteobacteria triggered a response in only 88 genes on average.

"Despite this broad range of responses to the different bacteria of the microbiome, we were astonished to pinpoint a central response: the plants practically always activate a core set of 24 genes," Vorholt says. But that's not all the team found: acting as a kind of volume control for the plant response, the activation intensity of these 24 genes provides information as to how extensively the bacteria have colonised the plant. This volume control also predicts how many additional genes the plant will activate as it adapts to the new arrivals.

Plants with defects in some of these 24 genes are more susceptible to harmful bacteria, Vorholt's team has shown. And since other studies had noticed that some genes in the core set are also involved in plant responses to osmotic shock or fungal infestation, the ETH researchers infer that the 24 genes constitute a general defensive response. "It looks like an immune training, even though the bacteria we used aren't pathogens, but rather partners in a natural community," Vorholt says.

Bacterial community out of control

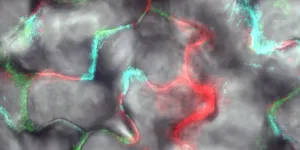

In the second study, Vorholt and her team explored how bacterial communities change when mutations cause a plant to be deficient in one or several genes. The team expected to see that genetic defects in receptors, which plants use to detect the presence of microbes, play a major role in the story.

What they didn't expect was that another genetic defect would have the biggest effect: if the plants were deficient in a certain enzyme, an NADPH oxidase, the bacterial community was thrown off-?kilter. Plants use this enzyme to produce highly reactive oxygen radicals, which have an antimicrobial effect. In the absence of this NADPH oxidase, microbes that under normal circumstances lived peacefully on the leaves developed into what are known as opportunistic pathogens.

Is the NADPH oxidase found among the core set of 24 genes responsible for general defensive response? "No, that would have been too good to be true," says Sebastian Pfeilmeier, a member of Vorholt's research group and lead author of the study. This is because the gene responsible for the NADPH oxidase is turned on prior to contact with microbes and because the enzyme is activated by chemical reactions governed by phosphorylation.

For Vorholt, the two studies show that synthetic microbiomes are a promising approach to investigating the complex interactions within different communities. "Since we can control and precisely engineer the communities, we can do much more than just observe what happens. In addition to simply determining cause and effect, we can understand them on a molecular level," Vorholt says. An ideal microbiome protects plants from diseases while also making them more resilient to drought and salty conditions. This is why the agricultural industry is among those interested in the team's results. They should help farmers harness the power of the microbiome in the future.

INFORMATION:

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-07-01

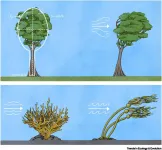

A team of scientists has devised a more accurate way to predict the effects of climate change on plants and animals -- and whether some will survive at all.

Frequently, ecologists assess an organism's fitness relative to the climate by quantifying its functional traits.

"These are physical properties you can measure -- height, diameter, the thickness of a tree," said UC Riverside biologist Tim Higham. "We believe more information is needed to understand how living things will respond to a changing world."

The team, led by Higham, outlines an alternative model for researchers in an article ...

2021-07-01

NEW YORK, NY (July 1, 2021)--Lowering levels of a hormone called PTHrP can prevent metastases and improve survival in mice with pancreatic cancer and could lead to a new way to treat patients, according to a study from cancer researchers at Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons and Herbert Irving Comprehensive Cancer Center and with collaborators at the University of Pennsylvania.

When patients are first diagnosed with pancreatic cancer, the cancer usually has spread to other organs. Because of these metastases, nearly all patients will succumb to their cancer within one year of diagnosis, but no drugs exist to prevent metastasis.

In an effort to find treatments, cancer researchers at Columbia--led by ...

2021-07-01

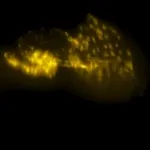

What if a microscope allowed us to explore the 3D microcosm of blood vessels, nerves, and cancer cells instantaneously in virtual reality? What if it could provide views from multiple directions in real time without physically moving the specimen and worked up to 100 times faster than current technology?

UT Southwestern scientists collaborated with colleagues in England and Australia to build and test a novel optical device that converts commonly used microscopes into multiangle projection imaging systems. The invention, described in an article in today's Nature Methods, could open new avenues ...

2021-07-01

SAN FRANCISCO, CA--June 28, 2021--While vaccines are doing a remarkable job of slowing the COVID-19 pandemic, infected people can still die from severe illness and new medications to treat them have been slow to arise. What kills these patients in the end doesn't seem to be the virus itself, but an over-reaction of their immune system that leads to massive inflammation and tissue damage.

By studying a type of immune cells called T cells, a team of Gladstone scientists has uncovered fundamental differences between patients who overcome severe COVID-19 and those who succumb to it. The team, working together with researchers from UC San Francisco and Emory University, also found that dying patients harbor relatively large numbers of T cells able to infiltrate the lung, which may contribute ...

2021-07-01

BUFFALO, N.Y. -- Patients with Type 2 diabetes who were prescribed SGLT2 inhibitors lost more weight than patients who received GLP-1 receptor agonists, according to a University at Buffalo-led study.

The research, which sought to evaluate the difference in weight loss caused by the antidiabetic medications -- both of which work to control blood sugar levels -- found that among 72 patients, people using SGLT2 inhibitors experienced a median weight loss of more than 6 pounds, while those on GLP-1 receptor agonists lost a median of 2.5 pounds.

The findings, published last month ...

2021-07-01

The adult brain is more malleable than previously thought, according to researchers from the Interdisciplinary Center Herzliya. They trained a 50-year-old man, blind from birth, to "see" by ear, and found that neural circuits in his brain formed so-called topographic maps - a type of brain organization previously thought to emerge only in infancy. This finding reported recently in END ...

2021-07-01

Rochester, Minn. -- Mayo Clinic researchers have discovered that genetic variants in a neuro-associated gene called SPTBN1 are responsible for causing a neurodevelopmental disorder. The study, published in Nature Genetics, is a first step in finding a potential therapeutic strategy for this disorder, and it increases the number of genes known to be associated with conditions that affect how the brain functions.

"The gene can now be included in genetic testing for people suspected of having a neurodevelopmental disorder, which may end the diagnostic odyssey these people and their families have endured," says Margot Cousin, Ph.D., a translational ...

2021-07-01

UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. -- In the late 1800s, scientists were stumped by the "yellow cells" they were observing within the tissues of certain temperate marine animals, including sea anemones, corals and jellyfish. Were these cells part of the animal or separate organisms? If separate, were they parasites or did they confer a benefit to the host?

In a paper published in the journal Nature in 1882, biologist Sir Patrick Geddes of Edinburgh University proffered that not only were these cells distinct entities, but they were also beneficial to the animals in which they lived. He assigned them to a new genus, Philozoon -- from the Greek phileo, meaning 'to love ...

2021-07-01

Giving women in India's Madhya Pradesh state greater digital control over their wages encouraged them to enter the labor force and liberalized their beliefs about working women, concluded a new study co-authored by Yale economists Rohini Pande and Charity Troyer Moore.

The study, published in the American Economic Review, found that a relatively simple intervention directed to poor women -- providing them access to their own bank accounts and direct deposit for their earnings from a federal workfare program, along with basic training on how to use local bank kiosks -- increased the amount ...

2021-07-01

Based on fossil finds, we know that the vast majority of species that once inhabited the earth have become extinct. For example, there are about 5,500 mammal species living on the planet today, but we know of at least 160,000 fossil species, so for every mammal species living today, there are at least 30 extinct ones. We therefore know with great certainty that the lineages of living things come and go along immense time scales. But what factors cause these lineages to come into being and disappear is still an unsolved question.

To investigate ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Unlocking the power of the microbiome