(Press-News.org) In the United States, nearly every pediatric doctor's visit begins with three measurements: weight, height and head circumference. Compared to average growth charts of children across the country, established in the 1970s, a child's numbers can confirm typical development or provide a diagnostic baseline to assess deviations from the curve. Yet, the brain, of vital importance to the child's development, is merely hinted at in these measurements.

Head circumference may indicate a head growth issue, which could be further investigated to determine if there is an issue with brain size or extra fluid. But now, in the age of noninvasive brain scanning such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), could researchers develop normalized growth curve charts for the brain?

That was the question Steven Schiff, Brush Chair Professor of Engineering at Penn State, and his multi-institution research team set out to answer. They published their results today (July 9) in the Journal of Neurosurgery, Pediatrics.

"Brain size research also has a very unfortunate history, as it was often used to attempt to scientifically prove one gender or race or culture of people as better than another," said Schiff, also a professor of engineering science and mechanics in the College of Engineering and of neurosurgery in the College of Medicine. "In this paper, we discuss the research going back about 150 years and then look at what the data of a contemporary cohort really tells us."

The researchers analyzed 1,067 brain scans of 505 healthy children, ages 13 days to 18 years old, from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Pediatric MRI Repository. To ensure a representative sample population across sex, race, socioeconomic status and geographic location, the MRI scans were taken sequentially over several years at hospitals and medical schools in California, Massachusetts, Missouri, Ohio, Pennsylvania and Texas. To ensure calibrated results, one person was established as a control and scanned at each site.

"The study of brain size and growth has a long and contentious history -- even in the era of MRI, studies defining normal brain volume growth patterns often include small sample sizes, limited algorithm technology, incomplete coverage of the pediatric age range and other issues," said first author Mallory R. Peterson, a Penn State student who is pursuing both a doctorate in engineering science and mechanics in the College of Engineering and a medical degree in the College of Medicine. She earned her bachelor of science degree in biomedical engineering from Penn State in 2016. "These studies have not addressed the relationship between brain growth and cerebrospinal fluid in depth, either. In this paper, we resolve both of these issues."

The first startling finding, according to Schiff and Peterson, was the difference in brain volume between male and female children. Even after adjusting for body size, males exhibited larger overall brain volume -- but specific brain structures did not differ in size between sexes, nor did cognitive ability.

"Clearly, sex-based differences do not account for intelligence -- we have known that for a long time, and this does not suggest differently," Schiff said. "The important thing here is that there is a difference in how the brains of male and female children grow. When you're diagnosing or treating a child, we need to know when a child's brain isn't growing normally."

The second finding was one of striking similarity rather than differences.

"Regardless of the sex or the size of the child, we unexpectedly found that the ratio between the size of the child's brain and the volume of fluid within the head -- cerebrospinal fluid -- was universal," Schiff said. "This fluid floats and protects the brain, serving a variety of functions as it flows through the brain. Although we have not recognized this tight normal ratio before, this relationship of fluid to brain is exactly what we try to regulate when we treat children for excess fluid in conditions of hydrocephalus."

The researchers plan to continue studying the ratio and its potential functions, as well as underlying mechanisms, in children and across the life span.

"The apparent universal nature of the age-dependent brain-cerebrospinal fluid ratio, regardless of sex or body size, suggests that the role of this ratio offers novel ways to characterize conditions affecting the childhood brain," Peterson said.

The researchers also settled a longstanding controversy in terms of the temporal lobe, according to Schiff. After two years of age, the left side of this brain structure -- where language function is typically localized -- was clearly larger than the right side throughout childhood. A portion of the temporal lobe called the hippocampus, which can be a cause of epilepsy, was larger on the right than the left as it grew during childhood.

"These normal growth curves for these critical structures often involved in epilepsy will help us determine when these structures are damaged and smaller than normal for age," said Schiff.

This approach to normal brain growth during childhood could help researchers understand normal from excessive volume loss throughout the later lifespan, according to Schiff.

"Brain volume peaks at puberty," Schiff said. "It then decreases as we age, and it decreases more rapidly in people with certain types of dementia. If we can better understand both brain growth and the ratio of brain to fluid at every age, we can not only improve how we diagnose clinical conditions, but also how we treat them."

INFORMATION:

Schiff also is a professor of physics in the Eberly College of Science, the founder of the Penn State Center for Neural Engineering and a researcher in the Penn State Neuroscience Institute and in the Huck Institutes of the Life Sciences' Center for Infectious Disease Dynamics. Other contributors include Venkateswararao Cherukuri, Penn State Center for Neural Engineering and Penn State School of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science; Joseph N. Paulson, Genentech Inc.; Paddy Ssentongo, Penn State Department of Engineering Science and Mechanics; Abhaya V. Kulkarni, University of Toronto and the Hospital for Sick Children; Benjamin C. Warf, Harvard Medical School and Boston Children's Hospital; and Vishal Monga, Penn State School of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science.

The Penn State and National Science Foundation Center for Healthcare Organization Transformation collaboration, the National Institutes of Health and the NIH Director's Transformative Award supported this research.

Growth impairment, a common complication of Crohn's disease in children, occurs more often in males than females, but the reasons are unclear. Now, a physician-scientist from Weill Cornell Medicine and NewYork-Presbyterian and colleagues at eight other centers have found that factors associated with statural growth differ by sex. Their recent publication, identified as the "Editor's Choice / Leading Off" article and receiving a mention on the cover of the June issue of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases, underscores the need for investigating and developing sex-specific treatment strategies for children with Crohn's disease, an approach that is not currently part ...

Nashville, Tenn., (3:40 EDT--July 9, 2021)--An analysis of MRI images of the tissue grafts used for patients who underwent surgery to repair the anterior cruciate knee ligament suggests grafts used from the quadriceps may be superior to tissue grafts from the hamstring. The research was presented today at the American Orthopaedic Society for Sports Medicine - Arthroscopy Association of North America Combined 2021 Annual Meeting.

Younger patients who required ACL reconstruction surgery have historically been treated with a hamstring graft to replace the injured ACL, but preliminary evidence suggests a graft from the quadriceps may be superior. Researchers from the Hospital for Special Surgery in New ...

Why do some Europeans discriminate against Muslim immigrants, and how can these instances of prejudice be reduced? Political scientist Nicholas Sambanis has spent the last few years looking into this question by conducting innovative studies at train stations across Germany involving willing participants, unknowing bystanders and, most recently, bags of lemons.

His newest study, co-authored with Donghyun Danny Choi at the University of Pittsburgh and Mathias Poertner at Texas A&M University, was published July 8 in the American Journal of Political Science and finds evidence of significant discrimination against Muslim women during everyday interactions with native Germans. That evidence comes from experimental interventions set up on train platforms ...

Plants have microscopically small pores on the surface of their leaves, the stomata. With their help, they regulate the influx of carbon dioxide for photosynthesis. They also use the stomata to prevent the loss of too much water and withering away during drought.

The stomatal pores are surrounded by two guard cells. If the internal pressure of these cells drops, they slacken and close the pore. If the pressure rises, the cells move apart and the pore widens.

The stomatal movements are thus regulated by the guard cells. Signalling pathways in these cells are so complex that it is difficult for humans to intervene with them directly. However, researchers of the Julius-Maximilians-Universität (JMU) Würzburg in ...

A research team co-led by UCL (University College London) has solved a decades-old mystery as to how Jupiter produces a spectacular burst of X-rays every few minutes.

The X-rays are part of Jupiter's aurora - bursts of visible and invisible light that occur when charged particles interact with the planet's atmosphere. A similar phenomenon occurs on Earth, creating the northern lights, but Jupiter's is much more powerful, releasing hundreds of gigawatts of energy, enough to briefly power all of human civilisation*.

In a new study, published in Science Advances, researchers combined close-up observations of Jupiter's environment by NASA's satellite Juno, which is currently orbiting the planet, with simultaneous X-ray ...

Two factors that play a key role in climate change - increased climate warming and elevated ozone levels - appear to have detrimental effects on soybean plant roots, their relationship with symbiotic microorganisms in the soil and the ways the plants sequester carbon.

The results, published in the July 9 edition of Science Advances, show few changes to the plant shoots aboveground but some distressing results underground, including an increased inability to hold carbon that instead gets released into the atmosphere as a greenhouse gas.

North Carolina State University researchers examined the interplay of warming and increased ozone levels with certain important underground organisms - arbuscular ...

A survey offered to transgender and nonbinary people across six continents and in thirteen languages shows that during the first months of the COVID-19 pandemic, many faced reduced access to gender-affirming resources, and this reduction was linked to poorer mental health. Brooke Jarrett of the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, Maryland, and colleagues present the findings in the open-access journal PLOS ONE on July 9.

Gender-affirming resources, which can include health care such as surgery and/or hormone therapy as well as gender affirming services and products --are well-known to significantly ...

Trust in science - but not trust in politicians or the media - significantly raises support across US racial groups for COVID-19 social distancing.

INFORMATION:

Article Title: The role of race and scientific trust on support for COVID-19 social distancing measures in the United States

Funding: The authors received no specific funding for this work.

Competing Interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Article URL: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0254127

...

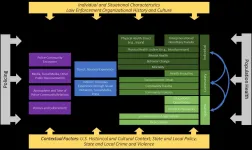

A specific police action, an arrest or a shooting, has an immediate and direct effect on the individuals involved, but how far and wide do the reverberations of that action spread through the community? What are the health consequences for a specific, though not necessarily geographically defined, population?

The authors of a new UW-led study looking into these questions write that because law enforcement directly interacts with a large number of people, "policing may be a conspicuous yet not-well understood driver of population health."

Understanding how law enforcement impacts the mental, physical, social and structural health and wellbeing of a community is a complex challenge, involving many academic and research ...

Meningitis is associated with high mortality and frequently causes severe sequelae. Newborn infants are particularly susceptible to this type of infection; they develop meningitis 30 times more often than the general population. Group B streptococcus (GBS) bacteria are the most common cause of neonatal meningitis, but they are rarely responsible for disease in adults. Scientists from the Institut Pasteur, in collaboration with Inserm, Université de Paris and Necker-Enfants Malades Hospital (AP-HP), set out to explain neonatal susceptibility to GBS meningitis. In a mouse model, they demonstrated that the immaturity of both the gut microbiota and epithelial barriers such as the gut and choroid plexus play a role in the susceptibility of newborn infants to bacterial meningitis caused by ...