(Press-News.org) The Lucinidae family, lucinids for short, comprises approximately 500 living species of bivalves. They are at least 400 million years old, according to fossil records, and have managed to colonize a wide variety of habitats, from beautiful beaches to the abyssal depths untouched by the sun over a kilometer below the sea surface. Their ability to thrive in a wide variety of habitats is made possible by their 'partner in crime', a sulfur-oxidizing bacterial symbiont that utilizes hydrogen sulfide, better known as 'rotten egg gas', as an energy source to power primary production. This process is not unlike photosynthesis used by plants, yet not dependent on sunlight, and generates enough sugars to feed both the symbiont and the lucinids themselves.

Striking up partnerships from near or far

Finding a suitable partner out in the wild is a matter of life and death for lucinids. They have to pick up their bacterial partners at a very early life stage when they settle in the sediment after their larval stage. From this time on, they rely on their bacterial symbionts for nutrition. However, bacterial cells are miniscule and the oceans are awash with a multitude of possible candidates. Typically, animals that rely so heavily on bacteria are expected to strike up partnerships with local residents. These microbes are likely to work best under the unique conditions of their local habitats. A new study based on metagenomic analyses of symbiotic bacteria in lucinids now reveals that this is not always the case: Some bacterial symbionts travel the globe and are true cosmopolitans.

Globally distributed symbionts

"Using state-of-art DNA-sequencing and genome assembling, we discovered that a single bacterial symbiont species was the most abundant symbiont in eight lucinid species spanning three oceans - the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans - across the tropics of both hemispheres," said Laetitia Wilkins from the Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology in Bremen, Germany, shared first author of the publication together with Jay Osvatic from the University of Vienna, Austria. "These symbionts are virtually all over the place." No other known symbiont is so successful at dispersal and establishing symbioses with lucinids, the researchers report. They named it Candidatus Thiodiazotropha taylori - "to acknowledge the wisdom of John Taylor from the Natural History Museum in London, who has devoted 25 years of his life to studying lucinid biology and taxonomy", as Osvatic pointed out.

"This unexpected finding challenges previous concepts that symbionts are acquired locally. It suggests that lucinid symbionts are much more mobile", Osvatic added. The remarkable flexibility in this partnership is advantageous to both host and symbiont, as it increases the likelihood of locating a compatible partner across diverse habitats all over the globe. Prior to this study, lucinid research has mainly been carried out in easily accessible locations. Now for the first time the team around Wilkins and Osvatic presents an expanded, global dataset that has led to and will continue to facilitate new discoveries and show how distant habitats might be connected.

Scientists collaborating to find collaborating organisms

Just like the relationships between symbionts and lucinid clams, this discovery would not have been possible without the scientists reaching out and forming collaborations across the world. "Our contacts (and now friends) across the world have given us access to an unprecedented diversity of lucinds, both direct from the beaches and from museums across the world", said Benedict Yuen from the University of Vienna, senior author of the paper. "We were given access to a wide variety of lucinid samples at the Natural History Museum in London through John Taylor. Samples were also collected personally by our team and collaborators Matthieu Leray in Panama, Yolanda Camacho in Costa Rica, Olivier Gros in Guadeloupe and Jan A. van Gils in Mauritania."

Also discovered: Two new species in cosy togetherness

Moreover, the extensive data collection of Wilkins, Osvatic and their team resulted in the discovery of two new lucinid symbionts, which have now been described and named after Miriam Weber and Christian Lott, both former researchers from the Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology in Bremen. These symbionts - now known as Thiodioazotropha weberae and lotti - are found in the clam Loripes orbiculatus on the Italian island of Elba, where the symbionts peacefully co-exist in the gills of the same host. "Before genomic analyses were used, it was assumed that each clam hosts only one species of symbionts", Wilkins explained. "However, many clams on Elba harbor two symbiont species. Miriam and Christian discovered this clam population in the bay of Fetovaia and it is thanks to them that we could amass a very powerful dataset on this symbiosis."

Next, the researchers want to find out how the symbionts travel. "They leave their bivalve home to traverse the globe", added co-senior author Jillian Petersen. 'Both beneficial symbionts such as Candidatus T. taylori but also pathogens can disperse in the environment, but we usually don't know how.'

INFORMATION:

Contact information:

Dr. Laetitia Wilkins

Department of Symbiosis

Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology

Celsiusstr. 1, 28359 Bremen, Germany

Tel.: +49 421 2028-8220

E-Mail: lwilkins@mpi-bremen.de

Dr. Fanni Aspetsberger

Press Officer

Celsiusstr. 1, 28359 Bremen, Germany

Tel.: +49 421 2028-9470

E-Mail: presse@mpi-bremen.de

Assoc. Prof. Dr. Jillian Petersen

WWTF Vienna Research Group Leader

University of Vienna

Althanstr. 14, 1090 Vienna, Austria

Tel.: +43 1 4277 91206

E-Mail: jillian.petersen@univie.ac.at

Dr. Benedict Yuen

Division of Microbial Ecology

University of Vienna

Althanstr. 14, 1090 Vienna, Austria

E-Mail: benedict.yuen@univie.ac.at

Jay Osvatic

Division of Microbial Ecology

University of Vienna

Althanstr. 14, 1090 Vienna, Austria

E-Mail: jay.osvatic@univie.ac.at

Original publication

Jay T. Osvatic†, Laetitia G. E. Wilkins†, Lukas Leibrecht, Matthieu Leray, Sarah Zauner, Julia Polzin, Yolanda Camacho, Olivier Gros, Jan A. van Gils, Jonathan A. Eisen, Jillian M. Petersen*, and Benedict Yuen* (2021): Global biogeography of chemosynthetic symbionts reveals both localized and globally-distributed symbiont groups. PNAS (July 12, 2021)

† shared first authorship

* shared last authorship

DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2104378118

Participating institutions:

Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology, Germany

University of Vienna, Austria

University of California, Davis, USA

Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, Republic of Panama?

Universidad de Costa Rica, Costa Rica

Universite? des Antilles, Guadeloupe

Royal Netherlands Institute for Sea Research, The Netherlands

BOSTON - By implementing a long-term, prospective approach to the development of celiac disease, a collaborative group of researchers has identified substantial microbial changes in the intestines of at-risk infants before disease onset. Using advanced genomic sequencing techniques, MassGeneral Hospital for Children (MGHfC) researchers, along with colleagues from institutions in Italy and the University of Maryland, College Park, uncovered distinct preclinical alterations in several species, pathways and metabolites in children who developed celiac disease compared to at-risk children who did not develop celiac disease.

As part of the MGHfC Celiac Disease, Genomic, Microbiome and Metabolomic (CDGEMM) Study, researchers ...

Communities trying to fight sea-level rise could inadvertently make flooding worse for their neighbors, according to a new study from the END ...

Better treatments of HER2-positive breast cancer are closer at hand, thanks to new research by a team led by Université de Montréal professor Jean-François Côté at the cytoskeleton organization and cell-migration research unit of the UdeM-affiliated Montreal Clinical Research Institute.

Published in PNAS, the journal of the U.S. National Academy of Sciences, the new research by Marie-Anne Goyette, a doctoral student in Côté's laboratory, reveals a highly promising therapeutic target to counter the HER2-positive breast cancer.

In HER2-positive breast cancer, a gene called HER2 is expressed that promotes an aggressive form of the disease. Affecting 20 per cent of ...

ITHACA, N.Y. - Traces of the gas phosphine point to volcanic activity on Venus, according to new research from Cornell University.

Last autumn, scientists revealed that phosphine was found in trace amounts in the planet's upper atmosphere. That discovery promised the slim possibility that phosphine serves as a biological signature for the hot, toxic planet.

Now Cornell scientists say the chemical fingerprint support a different and important scientific find: a geological signature, showing evidence of explosive volcanoes on the mysterious planet.

"The phosphine is not telling us about the biology ...

AUSTIN, Texas -- Lead exposure in childhood may lead to less mature and less healthy personalities in adulthood, according to a new study lead by psychology researchers at The University of Texas at Austin.

The study, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, sampled more than 1.5 million people in 269 U.S. counties and 37 European nations. Researchers found that those who grew up in areas with higher levels of atmospheric lead had less adaptive personalities in adulthood -- lower levels of conscientiousness and agreeableness and higher levels of neuroticism.

"Links between lead exposure and personality traits are quite impactful, because we take our personalities with us everywhere," ...

Sugarcane is one of the most productive plants on Earth, providing 80 percent of the sugar and 30 percent of the bioethanol produced worldwide. Its size and efficient use of water and light give it tremendous potential for the production of renewable value-added bioproducts and biofuels.

But the highly complex sugarcane genome poses challenges for conventional breeding, requiring more than a decade of trials for the development of an improved cultivar.

Two recently published innovations by University of Florida researchers at the Department of Energy's Center for Advanced Bioenergy and Bioproducts Innovation (CABBI) demonstrated the ...

Butterflies and moths have beautiful wings: the bright flare of an orange monarch, the vivid stripes of a swallowtail, the luminous green of a Luna moth. But some butterflies flutter on even more dramatic wings: parts of their wing, or sometimes the entire wing itself, are actually transparent.

Many aquatic organisms, including jellies and fish, are transparent. But transparent butterfly and moth wings are so arresting that merely catching a glimpse of one typically causes a human to lunge for a camera or at least point it out to their friends. These enigmatic, transparent butterfly wings have not been studied comprehensively.

Doris Gomez and Marianne Elias (French National Center for Scientific Research) set out to change that. Last week, along with a multidisciplinary ...

Chronic alcohol abuse and hepatitis can injure the liver and lead to fibrosis, the buildup of collagen and scar tissue. As a potential approach to treating liver fibrosis, University of California San Diego School of Medicine researchers and their collaborators are looking for ways to stop liver cells from producing collagen.

"So we thought...what if we take immunotoxins and try to get them to kill collagen-producing cells in the liver," said team lead Tatiana Kisseleva, MD, PhD, associate professor of surgery at UC San Diego School of Medicine. "If these antibodies carrying toxic molecules can find and bind the cells, the cells will eat up the 'gift' and die."

In a study published July 12, 2021 in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Kisseleva ...

Having a home near a busy airport certainly has its perks. It is close to many establishments and alleviates the problem of wading through endless traffic to catch flights. But it does come at a cost -- tolerating the jarring sounds of commercial airplanes during landing and takeoff.

Researchers at Texas A&M University have conducted a computational study that validates using a shape-memory alloy to reduce the unpleasant plane noise produced during landing. They noted that these materials could be inserted as passive, seamless fillers within airplane wings ...

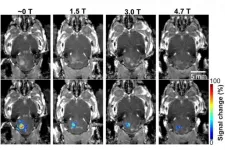

MRI-guided focused ultrasound combined with microbubbles can open the blood-brain barrier (BBB) and allow therapeutic drugs to reach the diseased brain location under the guidance of MRI. It is a promising technique that has been shown safe in patients with various brain diseases, such as Alzheimer's diseases, Parkinson's disease, ALS, and glioblastoma. While MRI has been commonly used for treatment guidance and assessment in preclinical research and clinical studies, until now, researchers did not know the impact of the static magnetic field generated by the MRI scanner on the BBB opening size and ...