Promising new research on aggressive breast cancer

2021-07-12

(Press-News.org) Better treatments of HER2-positive breast cancer are closer at hand, thanks to new research by a team led by Université de Montréal professor Jean-François Côté at the cytoskeleton organization and cell-migration research unit of the UdeM-affiliated Montreal Clinical Research Institute.

Published in PNAS, the journal of the U.S. National Academy of Sciences, the new research by Marie-Anne Goyette, a doctoral student in Côté's laboratory, reveals a highly promising therapeutic target to counter the HER2-positive breast cancer.

In HER2-positive breast cancer, a gene called HER2 is expressed that promotes an aggressive form of the disease. Affecting 20 per cent of women suffering from breast cancer in Canada, the HER2-positive subtype is associated with a poor prognosis.

What threatens the life of the majority of cancer patients is the power of tumour cells to spread and thus metastasize to other organs, which can interfere with vital body functions. Increasingly, personalized medicine has generated a lot of hope for patients expressing the HER2 gene, but relapses are frequent in many.

Immunotherapy is an important avenue for treating these drug-resistant patients, but so far with little apparent benefit. As a result, researchers are trying to deepen their understanding of the tumours' immune environment and thereby better target the treatments and those most likely to respond to them.

It is with this in mind that Côté's team studied an important phenomenon in solid tumours called hypoxia. Hypoxia is manifested by a lack of oxygen caused by the rapid growth of the tumour, and leads to the production of metastases, a weakened immune system and resistance to treatment. In short, by making tumours more aggressive while reducing the body's ability to defend itself, hypoxia promotes cancer progression, which can be fatal to those affected.

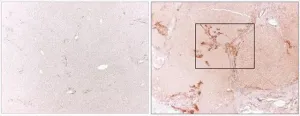

In a preclinical model, the IRCM team identified a protein called AXL whose action is crucial for hypoxia to take place. By blocking the action of this protein in the tumour, using various novel techniques, the team observed a recovery of blood vessels and a revitalization of the tumour's immune environment. Blocking the action of the tumour also reduced its ability to metastasize in other organs.

"It's as if we had succeeded, on the one hand, in breaking down the protective walls of the tumour against the immune system, thus making it more vulnerable to immunological treatments, and, on the other hand, in preventing the tumour from moving elsewhere," said Goyette, the new study's first author.

The potential of this study is all the more important as it opens the way for further research on the subject from the perspective of various fields of biomedical research, the researchers believe. The sharing of expertise has once again proved its worth, they say.

"Cutting-edge personalized medicine in immunology has faced significant resistance from this type of cancer and we had the expertise in molecular research to help overcome these obstacles," said Côté. "We have not only shed light on a central mechanism of the functioning of some of the most aggressive tumours, but in doing so we have also unveiled a way to create an environment conducive to more effective treatments."

INFORMATION:

About this study

"Targeting Axl favors an anti-tumorigenic microenvironment that enhances immunotherapy responses by decreasing Hif-1a levels" by Marie-Anne Goyette et al. was published July 12, 2021 in PNAS.

Funding was provided by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and their foundation, the Canadian Cancer Society, the Quebec Health Research Fund, the Quebec Cancer Foundation, the National Institutes of Health and the Transat Chair in Breast Cancer Research. This study was also made possible thanks to the collaboration of experts from Yale University, Universté de Montréal, McGill University and Université Laval.

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-07-12

ITHACA, N.Y. - Traces of the gas phosphine point to volcanic activity on Venus, according to new research from Cornell University.

Last autumn, scientists revealed that phosphine was found in trace amounts in the planet's upper atmosphere. That discovery promised the slim possibility that phosphine serves as a biological signature for the hot, toxic planet.

Now Cornell scientists say the chemical fingerprint support a different and important scientific find: a geological signature, showing evidence of explosive volcanoes on the mysterious planet.

"The phosphine is not telling us about the biology ...

2021-07-12

AUSTIN, Texas -- Lead exposure in childhood may lead to less mature and less healthy personalities in adulthood, according to a new study lead by psychology researchers at The University of Texas at Austin.

The study, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, sampled more than 1.5 million people in 269 U.S. counties and 37 European nations. Researchers found that those who grew up in areas with higher levels of atmospheric lead had less adaptive personalities in adulthood -- lower levels of conscientiousness and agreeableness and higher levels of neuroticism.

"Links between lead exposure and personality traits are quite impactful, because we take our personalities with us everywhere," ...

2021-07-12

Sugarcane is one of the most productive plants on Earth, providing 80 percent of the sugar and 30 percent of the bioethanol produced worldwide. Its size and efficient use of water and light give it tremendous potential for the production of renewable value-added bioproducts and biofuels.

But the highly complex sugarcane genome poses challenges for conventional breeding, requiring more than a decade of trials for the development of an improved cultivar.

Two recently published innovations by University of Florida researchers at the Department of Energy's Center for Advanced Bioenergy and Bioproducts Innovation (CABBI) demonstrated the ...

2021-07-12

Butterflies and moths have beautiful wings: the bright flare of an orange monarch, the vivid stripes of a swallowtail, the luminous green of a Luna moth. But some butterflies flutter on even more dramatic wings: parts of their wing, or sometimes the entire wing itself, are actually transparent.

Many aquatic organisms, including jellies and fish, are transparent. But transparent butterfly and moth wings are so arresting that merely catching a glimpse of one typically causes a human to lunge for a camera or at least point it out to their friends. These enigmatic, transparent butterfly wings have not been studied comprehensively.

Doris Gomez and Marianne Elias (French National Center for Scientific Research) set out to change that. Last week, along with a multidisciplinary ...

2021-07-12

Chronic alcohol abuse and hepatitis can injure the liver and lead to fibrosis, the buildup of collagen and scar tissue. As a potential approach to treating liver fibrosis, University of California San Diego School of Medicine researchers and their collaborators are looking for ways to stop liver cells from producing collagen.

"So we thought...what if we take immunotoxins and try to get them to kill collagen-producing cells in the liver," said team lead Tatiana Kisseleva, MD, PhD, associate professor of surgery at UC San Diego School of Medicine. "If these antibodies carrying toxic molecules can find and bind the cells, the cells will eat up the 'gift' and die."

In a study published July 12, 2021 in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Kisseleva ...

2021-07-12

Having a home near a busy airport certainly has its perks. It is close to many establishments and alleviates the problem of wading through endless traffic to catch flights. But it does come at a cost -- tolerating the jarring sounds of commercial airplanes during landing and takeoff.

Researchers at Texas A&M University have conducted a computational study that validates using a shape-memory alloy to reduce the unpleasant plane noise produced during landing. They noted that these materials could be inserted as passive, seamless fillers within airplane wings ...

2021-07-12

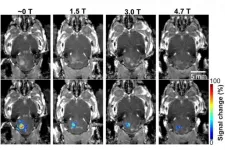

MRI-guided focused ultrasound combined with microbubbles can open the blood-brain barrier (BBB) and allow therapeutic drugs to reach the diseased brain location under the guidance of MRI. It is a promising technique that has been shown safe in patients with various brain diseases, such as Alzheimer's diseases, Parkinson's disease, ALS, and glioblastoma. While MRI has been commonly used for treatment guidance and assessment in preclinical research and clinical studies, until now, researchers did not know the impact of the static magnetic field generated by the MRI scanner on the BBB opening size and ...

2021-07-12

Children with a devastating genetic disorder characterized by severe motor disability and developmental delay have experienced sometimes dramatic improvements in a gene therapy trial launched at UCSF Benioff Children's Hospitals.

The trial includes seven children aged 4 to 9 born with deficiency of AADC, an enzyme involved in the synthesis of neurotransmitters, particularly dopamine, that leaves them unable to speak, feed themselves or hold up their head. Six of the children were treated at UCSF and one at Ohio State Wexner Medical Center.

Children in the study experienced improved motor function, better mood, and longer sleep, and were able to interact more fully with their ...

2021-07-12

Historically, shared resources such as forests, fishery stocks, and pasture lands have often been managed with an aim toward averting "tragedies of the commons," which are thought to result from selfish overuse. Writing in BioScience, Drs. Senay Yitbarek (University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill), Karen Bailey (University of Colorado Boulder), Nyeema Harris (Yale University), and colleagues critique this model, arguing that, all too often, such conservation has failed to acknowledge the complex socioecological interactions that undergird the health of resource ...

2021-07-12

Learning changes the brain, but when learning Braille different brain regions strengthen their connections at varied rates and time frames. A new study published in JNeurosci highlights the dynamic nature of learning-induced brain plasticity.

Learning new skills alters the brain's white matter, the nerve fibers connecting brain regions. When people learn to read tactile Braille, their somatosensory and visual cortices reorganize to accommodate the new demands. Prior studies only examined white matter before and after training, so the exact time course of the changes was not known.

Molendowska and Matuszewski et al. used diffusion MRI to measure changes in the white matter strength of sighted adults as they learned Braille over the course of eight months. They took measurements ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Promising new research on aggressive breast cancer