Climate regulation changed with the proliferation of marine animals and terrestrial plants

Geoscientific study traces carbon-silicon cycle over three billion years on the basis of lithium isotope levels

2021-07-15

(Press-News.org) Earth's climate was relatively stable for a long period of time. For three billion years, temperatures were mostly warm and carbon dioxide levels high - until a shift occurred about 400 million years ago. A new study suggests that the change at this time was accompanied by a fundamental alteration to the carbon-silicon cycle. "This transformation of what was a consistent status quo in the Precambrian era into the more unstable climate we see today was likely due to the emergence and spread of new life forms," said Professor Philip Pogge von Strandmann, a geoscientist at Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz (JGU). Together with researchers from Yale University, notably Boriana Kalderon-Asael and Professor Noah Planavsky, he has traced the long-term evolution of the carbon-silicon cycle with the help of lithium isotopes in marine sediments. This cycle is regarded as a key mechanism controlling the Earth's climate, as it regulates carbon dioxide levels and, with it, temperature. The researchers' findings have been published recently in Nature.

The carbon-silicon cycle is the key regulator of climate

The carbon-silicon cycle has kept Earth's climate stable over long periods of time, despite extensive variations in solar luminosity, in atmospheric oxygen concentrations, and the makeup of the Earth's crust. Such a stable climate created the conditions for long-term colonization of the Earth by life and allowed initially simple and later complex life forms to develop over billions of years. The carbon-silicon cycle contributes to this by regulating the level of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. Silicate rock is transformed into carbonate rock as a result of weathering and sedimentation, and carbonate rock is transformed back into silicate rock by, among other things, volcanism. When silicate rock is converted to carbonate rock, carbon dioxide is removed from the atmosphere, while the reverse process releases carbon dioxide once again. "We consider this to be the main mechanism by which Earth's climate is stabilized over the long term," explained Pogge von Strandmann.

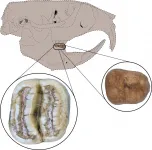

To trace long-term carbon-silicon cycles back in time and gain a better understanding of the precise relationships governing Earth's climate, the research team studied the ratio of lithium isotopes in marine carbonates. Lithium is present only in silicate rocks and their silicate and carbonate weathering products. The research team analyzed more than 600 samples deposited as sediments in shallow primeval marine waters and obtained from more than 100 different rock strata from around the world, including from Canada, Africa and China. "We used these samples to create a new database covering the past three billion years," Pogge von Strandmann pointed out.

These data show that the ratio of lithium-7 to lithium-6 isotopes in the oceans was low from three billion years ago to 400 million years ago, and then suddenly increased. It was precisely at this time that land plants evolved, while simultaneously marine animals with skeletons composed of silicon, such as sponges and radiolarians, spread throughout the oceans. "Both played a role, but as yet we do not know exactly how the processes are coupled," Professor Philip Pogge von Strandmann added.

The displacement of 'clay factories' to the land influences the carbon-silicon cycle

Research findings suggest that there was a massive change to the extent of the formation of clay, a secondary silicate rock composed of very fine particles, in the Earth's past - possibly due to an increase in clay formation on land and a decrease in the oceans. Clay formation is a crucial component of the carbon-silicon cycle and it influences the ratio of lithium isotopes. On land it is caused by the extensive weathering of silicate rocks, but in the oceans a range of different processes is involved. Increased continental clay formation is thought to have lowered carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere. In contrast, oceanic clay formation, known as "reverse weathering", releases CO2, so its decline will similarly have lowered atmospheric carbon dioxide levels.

According to the authors of the Nature paper, this suggests that the mode of climate regulation on Earth as well as the primary location where that process occurs has changed dramatically through time: "The shift from a Precambrian Earth state to the modern state can probably be attributed to major biological innovations - the radiation of sponges, radiolarians, diatoms and land plants." The result of this modification of climate regulation has been apparent ever since in the form of the frequent alternation between cold glacial periods on the one hand and warmer periods on the other. However, this climate instability, in turn, helps to accelerate evolution.

INFORMATION:

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-07-15

Burnout. It is a syndrome that is said to afflict humans who feel chronic stress. But after conducting a novel study using trail cameras showing the interactions between white-tailed deer fawns and predators, a Penn State researcher suggests that prey animals feel it, too.

"And you can understand why they do," said Asia Murphy, who recently graduated with a doctorate from Penn State's Intercollege Graduate Degree Program in Ecology. "Less than half of whitetail fawns live to see their first birthday, and many are killed by predators, such as coyotes, black ...

2021-07-15

Researchers from Skoltech have found a way to help computer vision algorithms process satellite images of the Earth more accurately even with very limited data for training. This will make various remote sensing tasks easier for machines and ultimately the people who use their data. The paper outlining the new results was published in the journal Remote Sensing.

Researchers have been using computer vision and machine learning techniques to help with environmental monitoring for a while now. Tasks that may seem tedious and prone to human error are normally a piece of cake for algorithms. But before a neural network can successfully, say, discriminate between the kinds of trees in a forested area, it needs to be trained, ...

2021-07-15

WHAT:

Among 6- and 7-year-olds who were born extremely preterm--before the 28th week of pregnancy--those who had more than two hours of screen time a day were more likely to have deficits in overall IQ, executive functioning (problem solving skills), impulse control and attention, according to a study funded by the National Institutes of Health. Similarly, those who had a television or computer in their bedrooms were more likely to have problems with impulse control and paying attention. The findings suggest that high amounts of screen time may ...

2021-07-15

Leesburg, VA, July 15, 2021--According to ARRS' American Journal of Roentgenology (AJR), return to routine screening for BI-RADS 3 lesions on supplemental automated whole-breast US (ABUS) substantially reduces the recall rate, while being unlikely to result in adverse outcome.

"This prospective study supports a recommendation for routine annual follow-up for BI-RADS 3 lesions at supplemental ABUS," wrote lead author Richard G. Barr of Northeastern Ohio Medical University in Rootstown.

From August 2013 to December 2016, Barr and colleagues' prospective study (NCT02650778) ...

2021-07-15

Undeniably the shark movie to end all shark movies, the 1975 blockbuster, Jaws, not only smashed box office expectations, but forever changed the way we felt about going into the water - and how we think about sharks.

Now, more than 40 years (and 100+ shark movies) on, people's fear of sharks persists, with researchers at the University of South Australia concerned about the negative impact that shark movies are having on conservation efforts of this often-endangered animal.

In a world-first study, conservation psychology researchers, UniSA's Dr Briana Le Busque and Associate Professor Carla Litchfield ...

2021-07-15

About 70-80% of crop losses due to microbial diseases are caused by fungi. Fungicides are key weapons in agriculture's arsenal, but they pose environmental risks. Over time, fungi also develop a resistance to fungicides, leading growers on an endless quest for new and improved ways to combat fungal diseases.

The latest development takes advantage of a natural plant defense against fungus. In a paper published in Biotechnology and Bioengineering, engineers and plant pathologists at UC Riverside describe a way to engineer a protein that blocks fungi from breaking down cell walls, as well as a way to produce this protein in quantity for external application as a natural fungicide. The work could lead to a new way of controlling plant disease that reduces reliance on conventional ...

2021-07-15

What are the fundamental skills that young children need to develop at the start of school for future academic success? While a large body of research shows strong links between cognitive skills (attention, memory, etc.) and academic skills on the one hand, and emotional skills on the other, in students from primary school to university, few studies have explored these links in children aged 3 to 6 in a school context. Researchers from the University of Geneva (UNIGE) and Valais University of Teacher Education, Switzerland (HEP-VS), in collaboration with teachers from Savoie in France and their pedagogical advisor, examined the links between emotion knowledge, cooperation, locomotor activity and numerical skills in 706 pupils aged 3 to 6. The results, to be read in the journal ...

2021-07-15

Contamination of urban lakes, rivers and surface water by human waste is creating pools of 'superbugs' in Low- and Middle-Income Countries (LMIC) - but improving access to clean water, sanitation and sewerage infrastructure could help to protect people's health, a new study reveals.

Researchers studied bodies of water in urban and rural sites in three areas of Bangladesh - Mymensingh, Shariatpur and Dhaka. They found more antibiotic resistant faecal coliforms in urban surface water compared to rural settings, consistent with reports of such bacteria in rivers across Asia.

Publishing their findings in mSystems today, researchers from the University of Birmingham and the International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh call for further research to quantify the drivers ...

2021-07-15

COVID-19 NEWS: CAN DIETARY SUPPLEMENTS HELP THE IMMUNE SYSTEM FIGHT CORONAVIRUS INFECTION?

Media Contact: Patrick Smith, pjsmith88@jhmi.edu

Johns Hopkins Medicine gastroenterologist Gerard Mullin, M.D., and a team of co-authors published an article May 11, 2021, in Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology that details the scientific rationale and possible benefits -- as well as possible drawbacks -- of several dietary supplements currently in clinical trials related to COVID-19 treatment.

According to business analysts, the U.S. nutritional supplement industry grew as much as 14.5% in 2020, due in large part to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Mullin, associate professor of medicine at the Johns Hopkins University ...

2021-07-15

GAINESVILLE, Fla. --- Two fossil teeth from a distant relative of North American gophers have scientists rethinking how some mammals reached the Caribbean Islands.

The teeth, excavated in northwest Puerto Rico, belong to a previously unknown rodent genus and species, now named Caribeomys merzeraudi. About the size of a mouse, C. merzeraudi is the Caribbean's smallest known rodent and one of the region's oldest, dating back about 29 million years.

It also represents the first discovery of a Caribbean rodent from a North American lineage, a finding that complicates an idea ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Climate regulation changed with the proliferation of marine animals and terrestrial plants

Geoscientific study traces carbon-silicon cycle over three billion years on the basis of lithium isotope levels