(Press-News.org) Add this to the list of real-life spidey senses: Harvard researchers have shown that jumping spiders are able to tell the difference between animate objects and inanimate objects -- an ability previously known only in vertebrates, including humans.

Using a specialized treadmill system and a point-light display animation, the team of scientists found that these spiders are able to recognize biological motion. This type of motion refers to the visual movements that come from living organisms when they are moving. The visual cue is how people, even babies, can tell someone is another person just by the way their bodies move. Many animals can do this, too.

The ability, which is critical for survival, is evolutionarily ancient since it is so widespread across vertebrates. The study from the Harvard team is believed to be the first demonstration of biological motion recognition in an invertebrate. The findings pose crucial questions about the evolutionary history of the ability and complex visual processing in non-vertebrates.

"[It] opens the possibility that such mechanisms might be widespread across the animal kingdom and not necessarily related to sociality," the researchers wrote in the paper, which published in PLOS Biology on Thursday.

The study was authored by a team of researchers who were John Harvard Distinguished Science Fellows during the time of the study or are current fellows. Massimo De Agrò, now a researcher at an animal comparative economics lab in Regensburg, Germany, led the work. Paul Shamble, a current fellow, and Daniela C. Rößler, and Kris Kim, former fellows, co-authored the study.

The researchers chose jumping spiders to test biological motion cues because the animals are among the most visually adept of all arthropods. With eight eyes, for example, vision plays a central role in a wide range of behaviors.

They placed the jumping spiders, a species called Menemerus semilimbatus, into a forced choice experiment. They suspended the spiders above a spherical treadmill so their legs could make contact with it. The spiders were kept in a fixed position so only its legs could move, transferring its intended direction to the sphere which spun freely because of a constant stream of compressed air shooting up below it.

(Friendly disclaimer: No spiders were harmed during the experiment and all were freed in the same place they were captured afterwards.)

Once in position, the spiders were presented two animations as stimuli. The animations were called point-light displays, each consisting of a dozen or so small lights (or points) that were attached to key joints of another spider so they could record its movements. The body itself is not visible, but the digital points give a body-plan outline and impression of a living organism. In humans, for example, it only takes about eleven dots on the main joints of the body for observers to correctly identify it as another person.

For the spiders, the displays followed the motion of another spider walking. Most of the displays gave the impression of seeing a living animal. Some of the displays were less real than others and one, called a random display, did not give the impression it was living.

The researchers then observed how the spiders reacted and which light display they turned toward on the treadmill. They found the spiders reacted to the different point-light displays by pivoting and facing them directly, which indicated that the spiders were able to recognize biological motion.

Curiously, the team found the spiders preferred rotating towards the more artificial displays and always toward the random one when it was part of the choice. They initially thought they would turn more toward the displays simulating another spider and possible danger, but the behavior made sense in the context of jumping spiders and how their secondary set of eyes work to decode information.

"The secondary eyes are looking at this point-light display of biological motion and it can already understand it, whereas the other random motion is weird and they don't understand what's there," De Agrò said.

The researchers hope to look into biological motion recognition in other invertebrates such as other insects or mollusks. The findings could lead to greater understanding of how these creatures perceive the world, De Agrò said.

INFORMATION:

Reducing greenhouse gas emissions (GHGs) and nitrogen water pollution from agriculture are top environmental priorities in the United States. Key to achieving climate goals is helping producers navigate carbon markets, while also helping the environment and improving farm income.

A new tool developed by a University of Minnesota research team allows farmers to create a budget balance sheet of any nitrogen reduction plans and see the economic and environmental cost, return and margins, all customized to fields under their management.

"With these numbers in mind, farmers can make more informed decisions on ...

(LOS ANGELES) - Many bodily functions in humans are manifested by mechanical deformations to the skin - from the stretching, bending and movement of muscles and joints to the flutter of a pulse at the wrist. These mechanical changes can be detected and monitored by measuring different levels of strain at various points throughout the body.

In recent years, much attention has been focused on wearable sensors to measure these strains for use in personal health monitoring. Some of these sensors can detect high-level (40-100%) strains, such as those associated with the movements of fingers ...

A new protein-based vaccine candidate combined with a potent adjuvant provided effective protection against SARS-CoV-2 when tested in animals, suggesting that the combination could add one more promising COVID-19 vaccine to the list of candidates for human use. The protein antigen, based on the receptor binding domain (RBD) of SARS-CoV-2, was expressed in yeast instead of mammalian cells - which the authors say could enable a scalable, temperature-stable, low-cost production process well suited for deployment in the developing world. In a study by Maria Pino and colleagues, the adjuvant ...

Concern has grown about prison systems' use of extended solitary confinement as a way to manage violent and disruptive incarcerated people. A new study identified groups that are more likely to be placed in extended solitary management (ESM). The study found that individuals sent to ESM differed considerably from the rest of the prison population in terms of mental health, education, language, race/ethnicity, and age.

The study, by researchers at Florida State University and the University of Cincinnati, appears in Justice Quarterly, a publication of the Academy of Criminal Justice Sciences.

"Many ...

URBANA, Ill. - Corn growers can choose from a wide array of products to make the most of their crop, but the latest could bring seaweed extract to a field near you. The marine product is just one class in a growing market of crop biostimulants marketed for corn.

Biostimulants benefit crops and soil, but the dizzying array of products has farmers confused, according to Fred Below, corn and soybean researcher at the University of Illinois.

"Farmers hear the term 'plant biostimulant' and think they all do the same thing, and can be used in the same way at the same time. But that's not the case. There's huge confusion ...

Earth's climate was relatively stable for a long period of time. For three billion years, temperatures were mostly warm and carbon dioxide levels high - until a shift occurred about 400 million years ago. A new study suggests that the change at this time was accompanied by a fundamental alteration to the carbon-silicon cycle. "This transformation of what was a consistent status quo in the Precambrian era into the more unstable climate we see today was likely due to the emergence and spread of new life forms," said Professor Philip Pogge von Strandmann, a geoscientist at Johannes ...

Burnout. It is a syndrome that is said to afflict humans who feel chronic stress. But after conducting a novel study using trail cameras showing the interactions between white-tailed deer fawns and predators, a Penn State researcher suggests that prey animals feel it, too.

"And you can understand why they do," said Asia Murphy, who recently graduated with a doctorate from Penn State's Intercollege Graduate Degree Program in Ecology. "Less than half of whitetail fawns live to see their first birthday, and many are killed by predators, such as coyotes, black ...

Researchers from Skoltech have found a way to help computer vision algorithms process satellite images of the Earth more accurately even with very limited data for training. This will make various remote sensing tasks easier for machines and ultimately the people who use their data. The paper outlining the new results was published in the journal Remote Sensing.

Researchers have been using computer vision and machine learning techniques to help with environmental monitoring for a while now. Tasks that may seem tedious and prone to human error are normally a piece of cake for algorithms. But before a neural network can successfully, say, discriminate between the kinds of trees in a forested area, it needs to be trained, ...

WHAT:

Among 6- and 7-year-olds who were born extremely preterm--before the 28th week of pregnancy--those who had more than two hours of screen time a day were more likely to have deficits in overall IQ, executive functioning (problem solving skills), impulse control and attention, according to a study funded by the National Institutes of Health. Similarly, those who had a television or computer in their bedrooms were more likely to have problems with impulse control and paying attention. The findings suggest that high amounts of screen time may ...

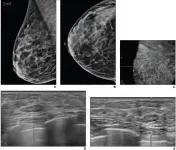

Leesburg, VA, July 15, 2021--According to ARRS' American Journal of Roentgenology (AJR), return to routine screening for BI-RADS 3 lesions on supplemental automated whole-breast US (ABUS) substantially reduces the recall rate, while being unlikely to result in adverse outcome.

"This prospective study supports a recommendation for routine annual follow-up for BI-RADS 3 lesions at supplemental ABUS," wrote lead author Richard G. Barr of Northeastern Ohio Medical University in Rootstown.

From August 2013 to December 2016, Barr and colleagues' prospective study (NCT02650778) ...