(Press-News.org) A commonly used scientific method to analyze a tiny amount of DNA in early human embryos fails to accurately reflect gene edits, according to new research led by scientists at Oregon Health & Science University.

The study, published today in the journal Nature Communications, involved sequencing the genomes of early human embryos that had undergone genome editing using the gene-editing tool CRISPR. The work calls into question the accuracy of a DNA-reading procedure that relies on amplifying a small amount of DNA for purposes of genetic testing.

In addition, the study reveals that gene editing to correct disease-causing mutations in early human embryos can also lead to unintended and potentially harmful changes in the genome.

Together, the findings raise a new scientific basis for caution for any scientist who may be poised to use genetically edited embryos to establish pregnancies. Although gene editing technologies hold promise in preventing and treating debilitating inherited diseases, the new study reveals limitations that must be overcome before gene-editing to establish a pregnancy can be deemed safe or effective.

“It tells you how little we know about editing the genome, and particularly how cells respond to the DNA damage that CRISPR induces,” said senior author Shoukhrat Mitalipov, Ph.D., director of the OHSU Center for Embryonic Cell and Gene Therapy; and, professor of obstetrics and gynecology, molecular and cellular biosciences, OHSU School of Medicine, OHSU Oregon National Primate Research Center. “Gene repair has great potential, but these new results show that we have a lot of work to do.”

The findings come during the Third International Summit on Human Genome Editing in London. On the eve of the last international summit, held in Hong Kong in November 2018, a Chinese scientist revealed the birth of the world’s first babies resulting from gene-edited embryos through an experiment that generated global condemnation.

Misdiagnosing embryos

Before an edited embryo can be transferred to establish a pregnancy, it is important to make sure the procedure worked as intended.

Because early human embryos consist of just a few cells, it’s not possible to collect enough genetic material to effectively analyze them. Instead, scientists interpret data from a small sample of DNA taken from a few or even a single cell, which then must be multiplied millions of times during a process known as whole genome amplification.

The same process — known as preimplantation genetic testing, or PGT — is often used to screen human embryos for various genetic conditions in patients undergoing in vitro fertilization.

Whole genome amplification has limitations that reduce the accuracy of genetic testing, said senior co-author Paula Amato, M.D., professor of obstetrics and gynecology in the OHSU School of Medicine.

“The concern is that we might be misdiagnosing embryos,” Amato said.

Amato, who uses in vitro fertilization to treat patients struggling with infertility as well as to prevent the transmission of inherited diseases, said PGT using more advanced technology is still clinically useful for detecting chromosomal abnormalities and genetic disorders caused by a single gene mutation transmitted from parent to child.

The study highlights the challenges of establishing the safety of gene-editing techniques.

“We may not be able to reliably predict that this embryo will result in a healthy baby,” Mitalipov said. “That’s a major problem.”

To overcome these issues, OHSU researchers, along with collaborators with research institutions in South Korea and China, established embryonic stem cell lines from gene-edited embryos. Embryonic stem cells grow indefinitely and provide ample DNA material that does not require whole genome amplification to analyze.

Researchers say the discovery highlights the error-prone nature of whole genome amplification and the need to verify edits in embryos by establishing embryonic stem cell lines.

Study verifies gene repair

Using embryonic stem cells, the new study verifies the process of gene repair that Mitalipov’s lab developed; the findings were published in the journal Nature in 2017 and verified in 2018.

In that study, scientists cut a specific target sequence on a mutant gene known to be carried by a sperm donor.

Researchers found that human embryos repair these breaks, using the normal copy of the gene from the other parent as a template. Mitalipov and co-authors confirmed that this process, known as gene conversion, occurs regularly in early human embryos following a double-strand break in their DNA. Such a repair, if used to establish a pregnancy through in vitro fertilization and embryo transfer, could theoretically prevent a known familial disease from being passed on to the child, as well as all future generations of the family.

In the study published in 2017, the OHSU researchers targeted a gene known to cause a deadly heart disease.

In this new publication, researchers targeted other discrete mutations using donated sperm and eggs, including one mutation known to cause hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, a condition in which the heart muscle becomes abnormally thick, and a different one associated with high cholesterol. In each case an enzyme known as Cas9, used in tandem with CRISPR, induced a double-strand break in DNA at the precise site of the mutation.

Creating problems

In addition to replicating and confirming the gene-repair mechanism reported in 2017, the new study examines what happens in the genome beyond the specific site where the mutant gene is repaired. And that’s where a problem can occur.

“In this paper we asked, ‘how extensive is that gene conversion repair mechanism?’” Amato said. “It turns out that it can be very lengthy.”

Extensive copying of the genome, from one parent to the other, creates a scenario known as loss of heterozygosity.

Every human being shares two versions, or alleles, of every gene on the human genome — one contributed from each parent. Most of the time, the alleles are identical, given 99.9% of any individual’s DNA sequence is shared with the rest of humanity. In some cases, however, one parent will carry a recessive disease-causing mutation that’s normally canceled out by the other parent’s dominant healthy version of the same gene.

These polymorphisms in the genetic code can be critically important. For example, a gene may encode a protein that protects against specific types of cancer.

“If you have one abnormal copy of a recessive mutation, that may pose no risk,” Amato said. “But if you have loss of heterozygosity leading to two mutant copies of the same tumor suppressor gene, now you’re at significantly increased risk for cancer.”

The more genetic code that’s copied, the greater the risk of dangerous genetic changes. In the new study, scientists measured gene conversion tracts ranging from a relatively small segment to as large as 18,600 base pairs of DNA.

In effect, the repair of one known mutation may create more problems than it solves.

“If you’re cutting in the middle of a chromosome, there could be 2,000 genes there,” Mitalipov said. “You’re fixing one tiny spot, but all these thousands of genes upstream and downstream may be affected.”

The finding suggests that much more research is needed to understand the mechanism at work in gene-editing before using it clinically to establish a pregnancy.

Studies conducted at the OHSU Center for Embryonic Cell and Gene Therapy were supported by OHSU institutional funds and a grant from the Burroughs Wellcome Fund.

END

Study reveals limitations in evaluating gene editing technology in human embryos

OHSU-led research identifies new scientific hurdles in using gene repair to prevent inherited disease

2023-03-07

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Keck Medicine of USC names Ikenna (Ike) Mmeje president and CEO of USC Arcadia Hospital

2023-03-07

LOS ANGELES — Keck Medicine of USC has named Ikenna (Ike) Mmeje president and CEO of USC Arcadia Hospital (USC-AH), effective March 13.

In this position, Mmeje will further the health system’s mission to expand access to specialized health care and research to the San Gabriel Valley and beyond. He will oversee all management and operations of the hospital, including corporate compliance, strategic plan implementation and fundraising.

“Mmeje will utilize his wealth of knowledge and experience running complex, high-performing hospitals in his new role leading USC Arcadia Hospital,” said Rod Hanners, CEO of Keck Medicine.

Mmeje replaces current ...

What makes a neural network remember?

2023-03-07

Computer models are an important tool for studying how the brain makes and stores memories and other types of complex information. But creating such models is a tricky business. Somehow, a symphony of signals – both biochemical and electrical – and a tangle of connections between neurons and other cell types creates the hardware for memories to take hold. Yet because neuroscientists don’t fully understand the underlying biology of the brain, encoding the process into a computer model in order to study it further has been a challenge.

Now, ...

How do microbes live off light?

2023-03-07

Plants convert light into a form of energy that they can use – a molecule called adenosine triphosphate (ATP) – through photosynthesis. This is a complex process that also produces sugar, which the plant can use for energy later, and oxygen. Some bacteria that live in the light-exposed layers of water sources can also convert light to ATP, but the process they use is simpler and less efficient than photosynthesis. Nonetheless, Technion - Israel Institute of Technology researchers now find this process isn’t as straightforward and limited as was previously thought.

Rhodopsins are the light-driven proton pumps ...

Commercial water purification system may have caused pathogen infection in 4 hospitalized patients

2023-03-07

1. Commercial water purification system may have caused pathogen infection in 4 hospitalized patients

Abstract: https://www.acpjournals.org/doi/10.7326/M22-3306

URL goes live when the embargo lifts

A study of 4 cardiac surgery patients in one hospital found that they developed Mycobacterium abscessus infections, a multidrug-resistant nontuberculous mycobacteria, potentially due to a commercial water purifier. The water purifier had been installed in the hospital to improve water palatability but was inadvertently removing chlorine from the supply lines feeding ice and water machines in the affected area of ...

Dr. B. Hadley Wilson is new American College of Cardiology President

2023-03-07

B. Hadley Wilson, MD, FACC, is the new president of the American College of Cardiology. Today marks the first day of his one-year term leading the global cardiovascular organization in its mission to transform cardiovascular care and improve heart health.

“Some of the best qualities of the ACC and its members are the commitment to patient care and the shared vision of a world where science, innovation and knowledge optimize and transform cardiovascular care and outcomes for all,” Wilson said. “I believe we all really practice what we preach. I am honored to lead an organization dedicated to innovating ...

Dr. Nicole Lohr is new chair of ACC Board of Governors

2023-03-07

Beginning today, Nicole L. Lohr, MD, PhD, FACC, will serve as chair of the American College of Cardiology Board of Governors (BOG) and secretary of the Board of Trustees. Her term will run one year from 2023-2024.

Lohr will lead governors from chapters representing all 50 states, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, Canada, Mexico and representatives from the U.S. health services. The BOG is the grassroots governing body of the ACC, a nonprofit cardiovascular medical society representing over 56,000 cardiologists and cardiovascular care team members around the world.

“I have spent the last 11 years finding ways to get involved in my ACC state chapter and in various ACC councils, ...

Sexual minority families fare as well as, and in some ways better than, ‘traditional’ ones

2023-03-07

Sexual minority families—where parental sexual orientation or gender identity is considered outside cultural, societal, or physiological norms—fare as well as, or better than, ‘traditional’ families with parents of the opposite sex, finds a pooled data analysis of the available evidence, published in the open access journal BMJ Global Health.

Parental sexual orientation isn’t an important determinant of children’s development, the analysis shows.

The number of children in families with lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender ...

Frequent socialising linked to longer lifespan of older people

2023-03-07

Frequent socialising may extend the lifespan of older people, suggests a study of more than 28,000 Chinese people, published online in the Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health.

Socialising nearly every day seems to be the most beneficial for a long life, the findings suggest.

In 2017, 962 million people around the globe were over 60, and their number is projected to double by 2050. Consequently, considerable attention has focused on the concept of ‘active’ or ‘successful’ ageing, an important component of which seems to be an active social life, note the researchers.

But most of the evidence for the health benefits of socialising ...

World first study into global daily air pollution shows almost nowhere on Earth is safe

2023-03-07

In a world first study of daily ambient fine particulate matter (PM2.5) across the globe, a Monash University study has found that only 0.18% of the global land area and 0.001% of the global population are exposed to levels of PM2.5 - the world’s leading environmental health risk factor – below levels of safety recommended by Word Health Organization (WHO). Importantly while daily levels have reduced in Europe and North America in the two decades to 2019, levels have increased Southern Asia, Australia, New Zealand, Latin America and the Caribbean, ...

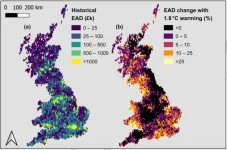

Pioneering study shows flood risks can still be considerably reduced if all global promises to cut carbon emissions are kept

2023-03-07

Annual damage caused by flooding in the UK could increase by more than a fifth over the next century due to climate change unless all international pledges to reduce carbon emissions are met, according to new research.

The study, led by the University of Bristol and global water risk modelling leader Fathom, reveals the first-ever dataset to assess flood hazard using the most recent Met Office climate projections which factor in the likely impact of climate change.

Its findings show the forecasted annual increase in national direct flood losses, defined as physical damage to property and businesses, due to climate change in the UK can be kept below 5% above recent historical levels. ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Scientists sharpen genetic maps to help pinpoint DNA changes that influence human health traits and disease risk

AI, monkey brains, and the virtue of small thinking

Firearm mortality and equitable access to trauma care in Chicago

Worldwide radiation dose in coronary artery disease diagnostic imaging

Heat and pregnancy

Superagers’ brains have a ‘resilience signature,’ and it’s all about neuron growth

New research sheds light on why eczema so often begins in childhood

Small models, big insights into vision

Finding new ways to kill bacteria

An endangered natural pharmacy hidden in coral reefs

The Frontiers of Knowledge Award goes to Charles Manski for incorporating uncertainty into economic research and its application to public policy analysis

Walter Koroshetz joins Dana Foundation as senior advisor

Next-generation CAR-T designs that could transform cancer treatment

As health care goes digital, patients are being left behind

A clinicopathologic analysis of 740 endometrial polyps: risk of premalignant changes and malignancy

Gibson Oncology, NIH to begin Phase 2 trials of LMP744 for treatment of first-time recurrent glioblastoma

Researchers develop a high-efficiency photocatalyst using iron instead of rare metals

Study finds no evidence of persistent tick-borne infection in people who link chronic illness to ticks

New system tracks blockchain money laundering faster and more accurately

In vitro antibacterial activity of crude extracts from Tithonia diversifolia (asteraceae) and Solanum torvum (solanaceae) against selected shigella species

Qiliang (Andy) Ding, PhD, named recipient of the 2026 ACMG Foundation Rising Scholar Trainee Award

Heat-free gas sensing: LED-driven electronic nose technology enhances multi-gas detection

Women more likely to choose wine from female winemakers

E-waste chemicals are appearing in dolphins and porpoises

Researchers warn: opioids aren’t effective for many acute pain conditions

Largest image of its kind shows hidden chemistry at the heart of the Milky Way

JBNU researchers review advances in pyrochlore oxide-based dielectric energy storage technology

Novel cellular phenomenon reveals how immune cells extract nuclear DNA from dying cells

Printable enzyme ink powers next-generation wearable biosensors

6 in 10 US women projected to have at least one type of cardiovascular disease by 2050

[Press-News.org] Study reveals limitations in evaluating gene editing technology in human embryosOHSU-led research identifies new scientific hurdles in using gene repair to prevent inherited disease