(Press-News.org) Developing and testing new treatments or vaccines for humans almost always requires animal trials, but these experiments can sometimes take years to complete and can raise ethical concerns about the animals’ treatment. Now, researchers reporting in ACS Central Science have developed a new testing platform that encapsulates B cells — some of the most important components of the immune system — into miniature “organoids” to make vaccine screening quicker and greatly reduce the number of animals needed.

Vaccines introduce the immune system to an antigen, which can be either part or all of a virus or bacterium, allowing the body to prepare itself for a future exposure by programming its B cells to make antibodies against the antigen. Certain bacteria coat themselves in a polysaccharide “disguise,” however, requiring specialized conjugate vaccines, such as those that protect against pneumonia and meningitis. In this type of approach, a piece of the antigenic polysaccharide is attached, or conjugated, to a carrier protein the body can recognize. But exactly how conjugate vaccines interact with B cells to induce an immune response isn’t fully understood.

The traditional way of testing vaccines involves injecting them into animals and waiting weeks or months for the result. And when developing a whole new class of vaccine or focusing on a new target, scientists often need to evaluate many vaccine candidates, requiring numerous animal studies. To speed up the process and address ethical concerns, researchers have begun exploring the use of organoids, which are small groups of cells that act like miniaturized organs, creating a simulated environment that reflects in vivo conditions. Hundreds of immune cell organoids can be constructed from the spleen of a single animal, greatly increasing testing throughput — which could help researchers keep up with the large numbers of compounds they can create and need to screen. So, Matthew DeLisa, Ankur Singh and colleagues wanted to see whether this method would provide results similar to those from animal experiments and whether the platform could be used to screen large numbers of glycoconjugate vaccine candidates.

To construct organoids, the researchers isolated B cells from mouse spleens, added cellular signaling molecules and structural components, then encapsulated everything in a synthetic hydrogel matrix. Next, they prepared conjugate vaccine candidates targeting the bacterium responsible for tularemia, or “rabbit fever,” for which an approved vaccine does not currently exist. Candidates were tested using both traditional in vivo mouse trials and the new organoid platform. The B cells reacted similarly in both formats and also provided insights into the several biochemical changes that occur as the cells mature into antibody-producing cells. As a result, the team found that the platform could be used to identify B cell clones that generate highly antigen-specific antibodies, which have a wide variety of potential applications. Though this work is preliminary, the researchers say that the organoid platform could help reduce the time it takes for new conjugate vaccines to be developed and evaluated.

The authors acknowledge funding from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the Defense Threat Reduction Agency, the National Institutes of Health, the Wellcome Leap HOPE Program and the National Science Foundation.

The paper’s abstract will be available on April 12 at 8 a.m. Eastern time here: http://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/acscentsci.2c01473

The American Chemical Society (ACS) is a nonprofit organization chartered by the U.S. Congress. ACS’ mission is to advance the broader chemistry enterprise and its practitioners for the benefit of Earth and all its people. The Society is a global leader in promoting excellence in science education and providing access to chemistry-related information and research through its multiple research solutions, peer-reviewed journals, scientific conferences, eBooks and weekly news periodical Chemical & Engineering News. ACS journals are among the most cited, most trusted and most read within the scientific literature; however, ACS itself does not conduct chemical research. As a leader in scientific information solutions, its CAS division partners with global innovators to accelerate breakthroughs by curating, connecting and analyzing the world’s scientific knowledge. ACS’ main offices are in Washington, D.C., and Columbus, Ohio.

To automatically receive news releases from the American Chemical Society, contact newsroom@acs.org.

Follow us: Twitter | Facebook | LinkedIn | Instagram

END

Testing vaccine candidates quickly with lab-grown mini-organs

2023-04-12

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Your fork could someday be made of sugar, wood powders and degrade on-demand (video)

2023-04-12

Single-use hard plastics are all around us: utensils, party decorations and food containers, to name a few examples. These items pile up in landfills, and many biodegradable versions stick around for months, requiring industrial composting systems to fully degrade. Now, researchers reporting in ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering have created a sturdy, lightweight material that disintegrates on-demand — and they made it from sugar and wood-derived powders. Watch a video about the material here.

Sturdy, degradable materials made from plants and other non-petroleum sources have come ...

Sugar molecule in blood can predict Alzheimer’s disease

2023-04-12

Early diagnosis and treatment of Alzheimer’s disease requires reliable and cost-effective screening methods. Researchers at Karolinska Institutet in Sweden have now discovered that a type of sugar molecule in blood is associated with the level of tau, a protein that plays a critical role in the development of severe dementia. The study, which is published in Alzheimer's & Dementia, can pave the way for a simple screening procedure able to predict onset ten years in advance.

“The role of glycans, ...

Starting small and simple - key to success for evolution of mammals

2023-04-12

The ancestors of modern mammals managed to evolve into one of the most successful animal lineages – the key was to start out small and simple, a new study reveals.

In many vertebrate groups, such as fishes and reptiles, the skull and lower jaw of animals with a backbone are composed of numerous bones. This was also the case in the earliest ancestors of modern mammals over 300 million years ago.

However, during evolution the number of skull bones was successively reduced in early mammals around 150 to 100 million years ago.

Publishing their findings today ...

New “AI scientist” combines theory and data to discover scientific equations

2023-04-12

In 1918, the American chemist Irving Langmuir published a paper examining the behavior of gas molecules sticking to a solid surface. Guided by the results of careful experiments, as well as his theory that solids offer discrete sites for the gas molecules to fill, he worked out a series of equations that describe how much gas will stick, given the pressure.

Now, about a hundred years later, an “AI scientist” developed by researchers at IBM Research, Samsung AI, and the University of Maryland, Baltimore County (UMBC) has reproduced a key part of Langmuir’s Nobel Prize-winning work. The system—artificial intelligence ...

When cells sense the cue for growth

2023-04-12

Researchers of the Genome Dynamics Project team at Tokyo Metropolitan Institute of Medical Science ·revealed new mechanism controlling cellular proliferation in response to serum, which triggers growth of resting cells.

One of the key pathways for cellular growth is the phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) –mTOR (mechanistic/mammalian target of rapamycin) pathway. mTOR regulates the cellular response to nutrient availability. Dysregulation of the mTOR signaling pathway is intimately involved in many human diseases, especially the multitude of different human cancers. This ...

Most plastic eaten by city vultures comes straight from food outlets

2023-04-12

Since the 1950s, humanity has produced an estimated 8.3bn tons of plastic, adding a further 380m tons to this amount each year. Only 9% of this gets recycled. The inevitable result is that plastic is everywhere, from the depths of the oceans to the summit of Everest – and notoriously, inside the tissues of humans and other organisms.

The long-term effects of ingested plastic on people aren’t yet known. But in rodents, ingested microplastics can impair the function of the liver, intestines, and exocrine and reproductive organs.

Especially ...

To more effectively sequester biomass and carbon, just add salt

2023-04-12

Reducing global greenhouse gas emissions is critical to avoiding a climate disaster, but current carbon removal methods are proving to be inadequate and costly. Now researchers from the University of California, Berkeley, have proposed a scalable solution that uses simple, inexpensive technologies to remove carbon from our atmosphere and safely store it for thousands of years.

As reported today in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, researchers propose growing biomass crops to capture carbon from the air, then burying the harvested vegetation in engineered dry biolandfills. This ...

How to cool your brain? These warm-blooded animals use their nose

2023-04-12

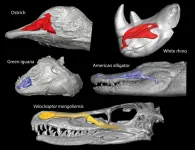

A research team led by Seishiro Tada and Takanobu Tsuihiji of the University of Tokyo shows that the living warm-blooded descendants of theropod dinosaurs evolved a better nasal cooling system aided by larger nasal cavities than cold-blooded animals. The study provides clues to the evolution of nasal cooling in warm-blooded animals from their theropod dinosaur ancestors.

Endotherms, or warm-blooded animals, maintain their high body temperature through internal heat sources. Birds, humans, and other mammals are endotherms. But ectotherms, or cold-blooded animals such as reptiles, use external heat sources to keep ...

It’s all in the wrist: energy-efficient robot hand learns how not to drop the ball

2023-04-12

Researchers have designed a low-cost, energy-efficient robotic hand that can grasp a range of objects – and not drop them – using just the movement of its wrist and the feeling in its ‘skin’.

Grasping objects of different sizes, shapes and textures is a problem that is easy for a human, but challenging for a robot. Researchers from the University of Cambridge designed a soft, 3D printed robotic hand that cannot independently move its fingers but can still carry out a range of complex movements.

The robot hand was trained to ...

How an African bird might inspire a better water bottle

2023-04-12

An extreme closeup of feathers from a bird with an uncanny ability to hold water while it flies could inspire the next generation of absorbent materials.

With high resolution microscopes and 3D technology, researchers at Johns Hopkins University and Massachusetts Institute of Technology captured an unprecedented view of feathers from the desert-dwelling sandgrouse, showcasing the singular architecture of their feathers and revealing for the first time how they can hold so much water.

“It’s super fascinating to see how nature managed to create structures so perfectly efficient to take ...