(Press-News.org) “The end of modern medicine as we know it.” That’s how the then-director general of the World Health Organization characterized the creeping problem of antimicrobial resistance in 2012. Antimicrobial resistance is the tendency of bacteria, fungus and other disease-causing microbes to evolve strategies to evade the medications humans have discovered and developed to fight them. The evolution of these so-called “super bugs” is an inevitable natural phenomenon, accelerated by misuse of existing drugs and intensified by the lack of new ones in the development pipeline.

Without antibiotics to manage common bacterial infections, small injuries and minor infections become potentially fatal encounters. In 2019, more than 2.8 million antimicrobial-resistant infections occurred in the United States, and more than 35,000 people died as a result, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). In the same year, about 1.25 million people died globally. A report from the United Nations issued earlier this year warned that number could rise to ten million global deaths annually if nothing is done to combat antimicrobial resistance.

For nearly 25 years, James Kirby, MD, director of the Clinical Microbiology Laboratory at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC), has worked to advance the fight against infectious diseases by finding and developing new, potent antimicrobials, and by better understanding how disease-causing bacteria make us sick. In a recent paper published in PLOS Biology, Kirby and colleagues investigated a naturally occurring antimicrobial agent discovered more than 80 years ago.

Using leading-edge technology, Kirby’s team demonstrated that chemical variants of the antibiotic, called streptothricins, showed potency against several contemporary drug-resistant strains of bacteria. The researchers also revealed the unique mechanism by which streptothricin fights off bacterial infections. What’s more, they showed the antibiotic had a therapeutic effect in an animal model at non-toxic concentrations. Taken together, the findings suggest streptothricin deserves further pre-clinical exploration as a potential therapy for the treatment of multi-drug resistant bacteria.

We asked Dr. Kirby to tell us more about this long-ignored antibiotic and how it could help humans stave off the problems of antimicrobial resistance a little longer.

Q: Why is it important to look for new antimicrobials? Can’t we preserve the drugs we have through more judicious use of antibiotics?

Stewardship is extremely important, but once you’re infected with one of these drug-resistant organisms, you need the tools to address it.

Much of modern medicine is predicated on making patients temporarily -- and sometimes for long periods of time -- immunosuppressed. When these patients get colonized with these multidrug-resistant organisms, it's very problematic. We need better antibiotics and more choices to address multidrug resistance.

We have to realize that this is a worldwide problem, and organisms know no borders. So, a management approach for using these therapies may work well in Boston but may not in other areas of the world where the resources aren't available to do appropriate stewardship.

Q: Your team investigated an antimicrobial discovered more than 80 years ago. Why was so little still known about it?

The first antibiotic, penicillin, was discovered in 1928 and mass produced for the market by the early 1940s. While a game-changing drug, it worked on only one of the two major classes of bacteria that infect people, what we call gram-positive bacteria. The gram-positive bacteria include staphylococcal infections and streptococcal infections which cause strep throat, skin infections and toxic shock. There still was not an antibiotic for the other half of bacteria that can cause human infections, known as gram-negative organisms.

In 1942, scientists discovered this antibiotic that they isolated from a soil bacterium called streptothricin, possibly addressing gram-negative organisms. A pharmaceutical company immediately licensed the rights to it, but the development program was dropped soon after when some patients developed renal or kidney toxicity. Part of the reason for not pursuing further research was that several additional antibiotics were identified soon thereafter which were also active against gram-negatives. So, streptothricin got shelved.

Q: What prompted you to look at streptothricin specifically now?

It was partly serendipity. My research laboratory is interested in finding new, or old and forgotten, solutions to treat highly drug-resistant gram-negative pathogens like E. coli or Klebsiella or Acinetobacter that we commonly see in hospitalized, immunocompromised patients. The problem is that they're increasingly resistant to many if not all of the antibiotics that we have available.

Part of our research is to understand how these superbugs cause disease. To do that, we need a way to manipulate the genomes of these organisms. Commonly, the way that's done is to create a change in the organism linked with the ability to resist a particular antibiotic that’s known as a selection agent. But for these super resistant gram-negative pathogens, there was really nothing we could use. These bugs were already resistant to everything.

We started searching around for drugs that we could use, and it turns out these super resistant bugs were highly susceptible to streptothricin, so we were able to use it as a selection agent to do these experiments.

As I read the literature on streptothricin and its history, I had the realization that it was not sufficiently explored. Here was this antibiotic with outstanding activity against gram-negative bacteria – and we confirmed that by testing it against a lot of different pathogens that we see in hospitals. That raised the question of whether we could get really good antibiotic activity at concentrations that are not going to cause damage to the animal or person in treatment.

Q: But it did cause kidney toxicity in people in 1942. What would be different now?

What scientists were isolating in 1942 was not as pure as what we are working with today. In fact, what was then called streptothricin is actually a mixture of several streptothricin variants. The natural mixture of different types of streptothricins is now referred to as nourseothricin.

In animal models, we tested whether we could kill the harmful microorganism without harming the host using a highly purified single streptothricin variant. We used a very famous strain of Klebsiella pneumoniae called the Nevada strain which was the first pan-drug-resistant, gram-negative organism isolated in the United States, an organism for which there was no treatment. A single dose cleared this organism from an infected animal model while avoiding any toxicity. It was really remarkable. We’re still in the very early stages of development, but I think we've validated that this is a compound that's worth investing in further studies to find even better variants that eventually will meet the properties of a human therapeutic.

Q. How does nourseothricin work to kill gram-negative bacteria?

That’s another really important part of our study. The mechanism hadn’t been figured out before and we showed that nourseothricin acts in a completely new way compared to any other type of antibiotic.

It works by inhibiting the ability of the organism to produce proteins in a very sneaky way. When a cell makes proteins, they make them off a blueprint or message that tells the cell what amino acids to link together to build the protein. Our studies help explain how this antibiotic confuses the machinery so that the message is read incorrectly, and it starts to put together gibberish. Essentially the cell gets poisoned because it's producing all this junk.

In the absence of new classes of antibiotics, we've been good at taking existing drugs like penicillin for example and modifying them; we've been making variations on the same theme. The problem with that is that the resistance mechanisms against penicillin and other drugs already exist. There's a huge environmental reservoir of resistance out there. Those existing mechanisms of resistance might not work perfectly well against your new variant of penicillin, but they will evolve very quickly to be able to conquer it.

So, there's recognition that what we really want is new classes of antibiotics that act in a novel way. That's why streptothricin’s action uncovered by our studies is so exciting. It works in a very unique way not seen with any other antibiotic, and that is very powerful because it means there's not this huge environmental reservoir of potential resistance.

Q. You emphasize these are early steps in development. What are the next steps?

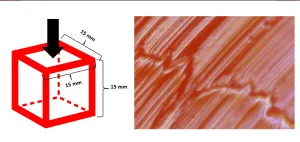

My lab is working very closely with colleagues at Northeastern University who figured out a way to synthesize streptothricin from scratch in a way that will allow us to cast many different variants. Then we can look for ones that have the ideal properties of high potency and reduced toxicity.

We are also continuing our collaboration with scientists at Case Western Reserve University Medical Center, diving more deeply to understand exactly how this antibiotic works. Then we can use that fundamental knowledge in our designs of future variants and be smarter about how we try to make the best antibiotic.

We have great collaborators that have allowed us to pursue a project that crosses multiple fields. This work is an example of collaborative science really at its best.

Co-authors included first author Christopher E. Morgan and Edward W. Yu of Case Western Reserve; Yoon-Suk Kang, Alex B. Green, Kenneth P. Smith, Lucius Chiaraviglio, Katherine A. Truelson, Katelyn E. Zulauf, Shade Rodriguez, and Anthony D. Kang of BIDMC; Matthew G. Dowgiallo, Brandon C. Miller, and Roman Manetsch of Northeastern University.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R21 AI140212, R01AI157208, F32 AI124590 and T32 AI007061). The HP D300 digital dispenser and TECAN M1000 were provided by TECAN, which had no role in study design, data collection/interpretation, manuscript preparation, or decision to publish. The authors declare no other competing interests.

About Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center

Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center is a leading academic medical center, where extraordinary care is supported by high-quality education and research. BIDMC is a teaching affiliate of Harvard Medical School, and consistently ranks as a national leader among independent hospitals in National Institutes of Health funding. BIDMC is the official hospital of the Boston Red Sox.

Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center is a part of Beth Israel Lahey Health, a health care system that brings together academic medical centers and teaching hospitals, community and specialty hospitals, more than 4,800 physicians and 36,000 employees in a shared mission to expand access to great care and advance the science and practice of medicine through groundbreaking research and education.

END

A potential new weapon in the war against superbugs

Researchers show an antibiotic discovered 80 years ago is effective against multi-drug resistant bacteria

2023-05-16

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Students at the University of Warwick show benefits of social prescribing for dementia

2023-05-16

Students at the University of Warwick are leading social prescribing research for dementia, highlighting the benefits of this innovative approach during Dementia Action Week.

The ground-breaking dementia café project, led by students from Warwick Medical School, is a shining example of the power of social prescribing in dementia care. By regularly connecting people with dementia to community activities, groups, and services, the project aims to meet practical, social, and emotional needs of people living with dementia while improving their overall health and well-being.

Social prescribing ...

Opportunities for improved dengue control in the US territories

2023-05-16

About The Article: This Viewpoint from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention discusses the prevalence of dengue infection in U.S. territories and opportunities to combat it, such as vaccines and novel vector control methods.

Authors: Alfonso C. Hernandez-Romieu, M.D., M.P.H., of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in San Juan, Puerto Rico, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jama.2023.8567)

Editor’s Note: Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, author contributions and affiliations, conflict ...

Suicide prevention: University of Ottawa researcher proposes assisted dying model to transform prevention

2023-05-16

Question: In your book you argue the suicidal are oppressed by structural suicidism, a hidden oppression.

Alexandre Baril: “I coined the term suicidism to refer to an oppressive system in which suicidal people experience multiple forms of injustice and violence. Our society is replete with horrific stories of suicidal individuals facing inhumane treatment after expressing their suicidal ideations. The intention is to save their lives at all costs and interventions range from being hospitalized and drugged ...

The physics of gummy candy

2023-05-16

WASHINGTON, May 16, 2023 – For gummy candies, texture might be even more important than taste. Biting into a hard, stale treat is disappointing, even if it still carries a burst of sweetness. Keeping gummies in good condition depends on their formulation and storage, both of which alter how the molecules in the candies link together.

In Physics of Fluids, by AIP Publishing, researchers from Ozyegin University and Middle East Technical University conducted a series of experiments that explore how changing key parts of the gummy-making process affects the final product, as well as how the candies ...

The economic burden of racial, ethnic, and educational health inequities in the US

2023-05-16

About The Study: According to two data sources, in 2018, the economic burden of health inequities for racial and ethnic minority populations (American Indian and Alaska Native, Asian, Black, Latino, and Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander populations) was $421 billion or $451 billion and the economic burden of health inequities for adults without a 4-year college degree was $940 billion or $978 billion. The economic burden of health inequities is unacceptably high and warrants investments in policies and interventions to promote health equity for racial and ethnic minorities and adults with less than a 4-year college degree.

Authors: Darrell ...

Excess mortality and years of potential life lost among the black population in the US

2023-05-16

About The Study: Based on data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, from 1999 through 2020, the Black population in the U.S. experienced more than 1.63 million excess deaths and more than 80 million excess years of life lost when compared with the white population. After a period of progress in reducing disparities, improvements stalled, and differences between the Black population and the white population worsened in 2020.

Authors: Harlan M. Krumholz, M.D., S.M., of the Yale School of Medicine ...

Engineers design sutures that can deliver drugs or sense inflammation

2023-05-16

CAMBRIDGE, MA -- Inspired by sutures developed thousands of years ago, MIT engineers have designed “smart” sutures that can not only hold tissue in place, but also detect inflammation and release drugs.

The new sutures are derived from animal tissue, similar to the “catgut” sutures first used by the ancient Romans. In a modern twist, the MIT team coated the sutures with hydrogels that can be embedded with sensors, drugs, or even cells that release therapeutic molecules.

“What we have is a suture that ...

Integration of AI decision aids to reduce workload and enhance efficiency in thyroid nodule management

2023-05-16

About The Study: The results of this diagnostic study involving 16 radiologists and 2,054 ultrasonographic images suggest that an optimized artificial intelligence (AI) strategy in thyroid nodule management may reduce diagnostic time-based costs without sacrificing diagnostic accuracy for senior radiologists, while the traditional all-AI strategy may still be more beneficial for junior radiologists.

Authors: Wei Wang, M.D., Ph.D., of Sun Yat-sen University in Guangzhou, China, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link ...

Use of immunization information systems in ascertainment of COVID-19 vaccinations for claims-based vaccine safety and effectiveness studies

2023-05-16

About The Study: The findings of this study of 5.1 million individuals suggested that supplementing COVID-19 claims records with Immunization Information Systems vaccination records substantially increased the number of individuals who were identified as vaccinated, yet potential under-recording remained. Improvements in reporting vaccination data to Immunization Information Systems infrastructures could allow frequent updates of vaccination status for all individuals and all vaccines.

Authors: Karen Schneider, Ph.D., of OptumServe Consulting in Falls ...

Estimated rates of incident and persistent chronic pain among US adults

2023-05-16

About The Study: In this analysis of nationally representative survey data, the incidence of chronic pain was high compared with other chronic diseases and conditions for which the incidence in the U.S. adult population is known, including diabetes, depression, and hypertension. This comparison emphasizes the high disease burden of chronic pain in the U.S. adult population and the need for both prevention and early management of pain before it can become chronic, especially for groups at higher risk.

Authors: Richard L. Nahin, M.P.H., Ph.D., of the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Maryland, is the corresponding author.

To access ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Indiana signs landmark education law to advance data science in schools

A new RNA therapy could help the heart repair itself

The dehumanization effect: New PSU research examines how abusive supervision impacts employee agency and burnout

New gel-based system allows bacteria to act as bioelectrical sensors

The power of photonics

From pioneer to leader: Alex Zhavoronkov chairs precision aging discussion and presents Luminary Award to OpenAI president at PMWC 2026

Bursting cancer-seeking microbubbles to deliver deadly drugs

In a South Carolina swamp, researchers uncover secrets of firefly synchrony

American Meteorological Society and partners issue statement on public availability of scientific evidence on climate change

How far will seniors go for a doctor visit? Often much farther than expected

Selfish sperm hijack genetic gatekeeper to kill healthy rivals

Excessive smartphone use associated with symptoms of eating disorder and body dissatisfaction in young people

‘Just-shoring’ puts justice at the center of critical minerals policy

A new method produces CAR-T cells to keep fighting disease longer

Scientists confirm existence of molecule long believed to occur in oxidation

The ghosts we see

ACC/AHA issue updated guideline for managing lipids, cholesterol

Targeting two flu proteins sharply reduces airborne spread

Heavy water expands energy potential of carbon nanotube yarns

AMS Science Preview: Mississippi River, ocean carbon storage, gender and floods

High-altitude survival gene may help reverse nerve damage

Spatially decoupling active-sites strategy proposed for efficient methanol synthesis from carbon dioxide

Recovery experiences of older adults and their caregivers after major elective noncardiac surgery

Geographic accessibility of deceased organ donor care units

How materials informatics aids photocatalyst design for hydrogen production

BSO recapitulates anti-obesity effects of sulfur amino acid restriction without bone loss

Chinese Neurosurgical Journal reports faster robot-assisted brain angiography

New study clarifies how temperature shapes sex development in leopard gecko

Major discovery sparks chain reactions in medicine, recyclable plastics - and more

Microbial clues uncover how wild songbirds respond to stress

[Press-News.org] A potential new weapon in the war against superbugsResearchers show an antibiotic discovered 80 years ago is effective against multi-drug resistant bacteria