(Press-News.org) In science, the explanation with the fewest assumptions is most likely to be true. Called “Occam’s Razor,” this principle has guided theory and experiment for centuries. But how do you compare between abstract concepts?

In a new paper, philosophers from UC Santa Barbara and UC Irvine discuss how to weigh the complexity of scientific theories by comparing their underlying mathematics. They aim to characterize the amount of structure a theory has using symmetry — or the aspects of an object that remain the same when other changes are made.

After much discussion, the authors ultimately doubt that symmetry will provide the framework they need. However, they do uncover why it’s such an excellent guide for understanding structure. Their paper appears in the journal Synthese.

“Scientific theories don’t often wear their interpretation on their sleeves, so it can be hard to say exactly what they’re telling you about the world,” said lead author Thomas Barrett, an associate professor in UC Santa Barbara’s philosophy department. “Especially modern theories. They just get more mathematical by the century.” Understanding the amount of structure in different theories can help us make sense of what they’re saying, and even give us reasons to prefer one over another.

Structure can also help us recognize when two ideas are really the same theory, just in different clothes. For instance, in the early 20th century, Werner Heisenberg and Erwin Schrödinger formulated two separate theories of quantum mechanics. “And they hated each other’s theories,” Barrett said. Schrödinger argued that his colleague’s theory “lacked visualizability.” Meanwhile, Heisenberg found Schrödinger’s theory “repulsive” and claimed that “what Schrödinger writes about visualizability [...] is crap.”

But while the two concepts appeared radically different, they actually made the same predictions. About a decade later, their colleague John von Neumann demonstrated that the formulations were mathematically equivalent.

Apples and oranges

A common way to examine a mathematical object is to look at its symmetries. The idea is that more symmetric objects have simpler structures. For instance, compare a circle — which has infinitely many rotational and reflective symmetries — to an arrow, which has only one. In this sense, the circle is simpler than the arrow, and requires less mathematics to describe.

The authors extend this rubric to more abstract mathematics using automorphisms. These functions compare various parts of an object that are, in some sense, “the same” as each other. Automorphisms give us a heuristic for measuring the structure of different theories: More complex theories have fewer automorphisms.

In 2012, two philosophers proposed a way to compare the structural complexity of different theories. A mathematical object X has at least as much structure as another, Y, if and only if the automorphisms of X are a subset of those of Y. Consider the circle again. Now compare it to a circle that is colored half red. The shaded circle now has only some of the symmetries it used to, on account of the extra structure that was added to the system.

This was a good try, but it relied too much on the objects having the same type of symmetries. This works well for shapes, but falls apart for more complicated mathematics.

Isaac Wilhelm, at the National University of Singapore, attempted to fix this sensitivity. We should be able to compare different types of symmetry groups as long as we can find a correspondence between them that preserves each one’s internal framework. For example, labeling a blueprint establishes a correspondence between a picture and a building that preserves the building’s internal layout.

The change allows us to compare the structures of very different mathematical theories, but it also spits out incorrect answers. “Unfortunately, Wilhelm went a step too far there,” Barrett said. “Not just any correspondence will do.”

A challenging endeavor

In their recent paper, Barrett and his co-authors, JB Manchak and James Weatherall, tried to salvage their colleague’s progress by restricting the type of symmetries, or automorphisms, they would consider. Perhaps only a correspondence that arises from the underlying objects (e.g. the circle and the arrow), not their symmetry groups, is kosher.

Unfortunately, this attempt fell short as well. In fact, it seems that using symmetries to compare mathematical structure may be doomed by principle. Consider an asymmetric shape. An ink blot, perhaps. Well, there’s more than one ink stain in the world, all of which are completely asymmetric and completely different from one another. But, they all have the same symmetry group — namely, none — so all these systems classify the ink blots as having the same complexity even if some are far messier than others.

This ink blot example reveals that we can’t tell everything about an object’s structural complexity just by looking at its symmetries. As Barrett explained, the number of symmetries an object admits bottoms out at zero. But there isn’t a corresponding ceiling to the amount of complexity an object can have. This mismatch creates the illusion of an upper limit for structural complexity.

And therein the authors expose the true issue. The concept of symmetry is powerful for describing structure. However, it doesn’t capture enough information about a mathematical object — and the scientific theory it represents — to allow for a thorough comparison of complexity. The search for a system that can do this will continue to keep scholars busy.

A glimmer of hope

While symmetry might not provide the solution the authors hoped for, they uncover a key insight: Symmetries touch on the concepts that an object naturally and organically comes equipped with. In this way, they can be used to compare the structures of different theories and systems. “This idea gives you an intuitive explanation for why symmetries are a good guide to structure,” Barrett said. The authors write that this idea is worth keeping, even if philosophers have to abandon using automorphisms to compare structure.

Fortunately, automorphisms aren’t the only kind of symmetry in mathematics. For instance, instead of looking only at global symmetries, we can look at symmetries of local regions and compare these as well. Barrett is currently investigating where this will lead and working to describe what it means to define one structure in terms of another.

Although clarity still eludes us, this paper gives philosophers a goal. We don’t know how far along we are in this challenging climb to the summit of understanding. The route ahead is shrouded in mist, and there may not even be a summit to reach. But symmetry provides a hold to anchor our ropes as we continue climbing.

END

Sharpening Occam’s Razor

A new perspective on structure and complexity

2023-06-14

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

C-Path’s PSTC receives positive FDA response for drug-induced pancreatic injury biomarkers

2023-06-14

Safety biomarkers aim to provide an additional tool for detecting acute drug-induced pancreatic injury (DIPI) in phase 1 clinical trials

TUCSON, Ariz., June 13, 2023 — Critical Path Institute (C-Path) today announced that the Biomarker Qualification Program (BQP) at the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) in the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued a Biomarker Letter of Support (LOS) for four pancreatic injury safety biomarkers identified and evaluated by C-Path’s Predictive Safety Testing Consortium's (PSTC) Pancreatic Injury Working Group (PIWG).

This set of biomarkers will help increase the ability ...

Breaking barriers: Advancements in meta-holographic display enable ultraviolet domain holograms

2023-06-14

The term meta means a concept of transcendence or surpassing, and when applied to materials, metamaterials encompass artificially engineered substances that exhibit properties not naturally found in the environment. Metasurfaces, characterized by their thinness and lightness, have garnered considerable interest as a potential component for incorporation into portable augmented reality (AR) and virtual reality (VR) devices to facilitate holographic generation. Nonetheless, it is important to note that metasurfaces have inherent limitations, such ...

Bhopal explosion may have heightened risk of disability and cancer among future generations

2023-06-14

The Bhopal gas explosion in 1984—one of India’s worst industrial disasters—may have heightened the risk of disability and cancer in later life among future generations, curbed their educational attainment, and prompted a fall in the proportion of male births the following year, suggests research in the open access journal BMJ Open.

The disaster is likely to have affected people across a substantially more extensive area than previous evidence suggested, say the researchers.

During the incident, toxic ...

NHS “flying blind” in attempt to tackle ethnic inequalities in care, warns expert

2023-06-14

The NHS will be “flying blind” in its attempts to meet its legal, and moral, obligation to eliminate ethnic inequalities in health and care until longstanding problems with the quality of ethnicity data are resolved, warns an expert in The BMJ today.

Inequalities in health and care between ethnic groups have been documented for decades, explains Sarah Scobie at the Nuffield Trust. But she argues that analysis by broad ethnic groups (white, Asian, black, and mixed) can mask substantial variation within them.

An accompanying infographic presents some of these disparities across a range ...

Timing of childhood adversity is associated with unique epigenetic patterns in adolescents

2023-06-14

BOSTON—Childhood adversity—circumstances that threaten to a child’s physical or psychological well-being--has long been associated with poorer physical and mental health throughout life, such as greater risks of developing cardiac disease, cancer, or depression. It remains unclear, however, when and how the effects of childhood adversity become biologically embedded to influence health outcomes in children, adolescents, and adults.

A team of researchers at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH), a founding member of Mass General Brigham (MGB), previously showed that exposure to adversity between ages 3 to 5 has a ...

Lockdown children played on, study finds, despite being stuck at home

2023-06-14

Children displayed a resilient capacity to continue playing during peak COVID-19, a study has found, even though their options to do so became more limited while under stay-at-home orders.

The research, by academics at the University of Cambridge, interviewed children themselves about their playing habits during the pandemic. Without disputing the consensus that COVID-19 impeded children’s healthy development, it does suggest that they were able to adapt their play habits to their changed circumstances.

Children largely expressed ...

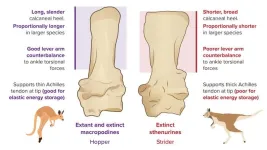

Skipping evolution: some kangaroos didn’t hop, scientists explain

2023-06-14

Extinct kangaroos used alternative methods to their famous hop according to comprehensive analysis from University of Bristol and the University of Uppsala scientists.

Although hopping is regarded as a pinnacle of kangaroo evolution, the researchers highlight that other kinds of large kangaroos, in the not too distant past, likely moved in different ways such as striding on two legs or traversing on all fours.

In the review, published in Alcheringa: An Australasian Journal of Palaeontology, the team shows that there are other ways to be an evolutionary ...

Light pollution confuses coastal woodlouse

2023-06-14

Artificial night-time light confuses a colour-changing coastal woodlouse, new research shows.

The sea slater is an inch-long woodlouse that lives around the high-tide line and is common in the UK and Europe.

Sea slaters forage at night and can change colour to blend in and conceal themselves from predators.

The new study, by the University of Exeter, tested the effects of a single-point light source (which casts clear shadows) and “diffuse” light (similar to “skyglow” found near towns and cities).

While the single light did not interfere with the sea slaters’ camouflage, diffuse light caused them to turn ...

Giving birth outside of working hours in England is safe, suggests study

2023-06-14

A new study suggests that between 2005 and 2014, for almost all births in England, being born outside of working hours did not carry a significantly higher risk of death to the baby from anoxia (lack of oxygen) or trauma, when compared to births during working hours.

The finding runs contrary to an assumed, wider ‘weekend effect,’ with previously reported research suggesting a significantly higher risk of death for births outside of working hours or at weekends.

The current study from City, University of London ...

Brighter nights risk extinguishing glow-worm twinkle

2023-06-14

The bright lights of big cities are wonders of the modern world; intended to help us work, stay safe and enjoy the world around us long after the sun has set. While artificial light has been great for increasing human productivity, some nocturnal animals, and even people, pay a price for this illumination. From increasing the amount of time that predators are active to disrupting migrations, light pollution affects many animals; but how do animals that use their own luminescence to lure food or attract mates fair against this new, brighter background? Female common glow-worms (Lampyris noctiluca) emit a green glow from their abdomen to ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Celebrity dolphin of Venice doesn’t need special protection – except from humans

Tulane study reveals key differences in long-term brain effects of COVID-19 and flu

The long standing commercialization challenge of lithium batteries, often called the dream battery, has been solved.

New method to remove toxic PFAS chemicals from water

The nanozymes hypothesis of the origin of life (on Earth) proposed

Microalgae-derived biochar enables fast, low-cost detection of hydrogen peroxide

Researchers highlight promise of biochar composites for sustainable 3D printing

Machine learning helps design low-cost biochar to fight phosphorus pollution in lakes

Urine tests confirm alcohol consumption in wild African chimpanzees

Barshop Institute to receive up to $38 million from ARPA-H, anchoring UT San Antonio as a national leader in aging and healthy longevity science

Anion-cation synergistic additives solve the "performance triangle" problem in zinc-iodine batteries

Ancient diets reveal surprising survival strategies in prehistoric Poland

Pre-pregnancy parental overweight/obesity linked to next generation’s heightened fatty liver disease risk

Obstructive sleep apnoea may cost UK + US economies billions in lost productivity

Guidelines set new playbook for pediatric clinical trial reporting

Adolescent cannabis use may follow the same pattern as alcohol use

Lifespan-extending treatments increase variation in age at time of death

From ancient myths to ‘Indo-manga’: Artists in the Global South are reframing the comic

Putting some ‘muscle’ into material design

House fires release harmful compounds into the air

Novel structural insights into Phytophthora effectors challenge long-held assumptions in plant pathology

Q&A: Researchers discuss potential solutions for the feedback loop affecting scientific publishing

A new ecological model highlights how fluctuating environments push microbes to work together

Chapman University researcher warns of structural risks at Grand Renaissance Dam putting property and lives in danger

Courtship is complicated, even in fruit flies

Columbia announces ARPA-H contract to advance science of healthy aging

New NYUAD study reveals hidden stress facing coral reef fish in the Arabian Gulf

36 months later: Distance learning in the wake of COVID-19

Blaming beavers for flood damage is bad policy and bad science, Concordia research shows

The new ‘forever’ contaminant? SFU study raises alarm on marine fiberglass pollution

[Press-News.org] Sharpening Occam’s RazorA new perspective on structure and complexity