(Press-News.org) CAMBRIDGE, Mass. -- When your laptop or smartphone heats up, it’s due to energy that’s lost in translation. The same goes for power lines that transmit electricity between cities. In fact, around 10 percent of the generated energy is lost in the transmission of electricity. That’s because the electrons that carry electric charge do so as free agents, bumping and grazing against other electrons as they move collectively through power cords and transmission lines. All this jostling generates friction, and, ultimately, heat.

But when electrons pair up, they can rise above the fray and glide through a material without friction. This “superconducting” behavior occurs in a range of materials, though at ultracold temperatures. If these materials can be made to superconduct closer to room temperature, they could pave the way for zero-loss devices, such as heat-free laptops and phones, and ultraefficient power lines. But first, scientists will have to understand how electrons pair up in the first place.

Now, new snapshots of particles pairing up in a cloud of atoms can provide clues to how electrons pair up in a superconducting material. The snapshots were taken by MIT physicists and are the first images that directly capture the pairing of fermions — a major class of particles that includes electrons, as well as protons, neutrons, and certain types of atoms.

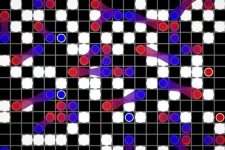

In this case, the MIT team worked with fermions in the form of potassium-40 atoms, and under conditions that simulate the behavior of electrons in certain superconducting materials. They developed a technique to image a supercooled cloud of potassium-40 atoms, which allowed them to observe the particles pairing up, even when separated by a small distance. They could also pick out interesting patterns and behaviors, such as a the way pairs formed checkerboards, which were disturbed by lonely singles passing by.

The observations, reported today in Science, can serve as a visual blueprint for how electrons may pair up in superconducting materials. The results may also help to describe how neutrons pair up to form an intensely dense and churning superfluid within neutron stars.

“Fermion pairing is at the basis of superconductivity and many phenomena in nuclear physics,” says study author Martin Zwierlein, the Thomas A. Frank Professor of Physics at MIT. “But no one had seen this pairing in situ. So it was just breathtaking to then finally see these images onscreen, faithfully.”

The study’s co-authors include Thomas Hartke, Botond Oreg, Carter Turnbaugh, and Ningyuan Jia, all members of MIT’s Department of Physics, the MIT-Harvard Center for Ultracold Atoms, and the Research Laboratory of Electronics.

A decent view

To directly observe electrons pair up is an impossible task. They are simply too small and too fast to capture with existing imaging techniques. To understand their behavior, physicists like Zwierlein have looked to analogous systems of atoms. Both electrons and certain atoms, despite their difference in size, are similar in that they are fermions — particles that exhibit a property known as “half-integer spin.” When fermions of opposite spin interact, they can pair up, as electrons do in superconductors, and as certain atoms do in a cloud of gas.

Zwierlein’s group has been studying the behavior of potassium-40 atoms, which are known fermions, that can be prepared in one of two spin states. When a potassium atom of one spin interacts with an atom of another spin, they can form a pair, similar to superconducting electrons. But under normal, room-temperature conditions, the atoms interact in a blur that is difficult to capture.

To get a decent view of their behavior, Zwierlein and his colleagues study the particles as a very dilute gas of about 1,000 atoms, that they place under ultracold, nanokelvin conditions that slow the atoms to a crawl. The researchers also contain the gas within an optical lattice, or a grid of laser light that the atoms can hop within, and that the researchers can use as a map to pinpoint the atoms’ precise locations.

In their new study, the team made enhancements to their existing technique for imaging fermions that enabled them to momentarily freeze the atoms in place, then take snapshots separately of potassium-40 atoms with one particular spin or the other. The researchers could then overlay an image of one atom type over the other, and look to see where the two types paired up, and how.

“It was bloody difficult to get to a point where we could actually take these images,” Zwierlein says. “You can imagine at first getting big fat holes in your imaging, your atoms running away, nothing is working. We’ve had terribly complicated problems to solve in the lab through the years, and the students had great stamina, and finally, to be able to see these images was absolutely elating.”

Pair dance

What the team saw was pairing behavior among the atoms that was predicted by the Hubbard model — a widely held theory believed to hold they key to the behavior of electrons in high-temperature superconductors, materials that exhibit superconductivity at relatively high (though still very cold) temperatures. Predictions of how electrons pair up in these materials have been tested through this model, but never directly observed until now.

The team created and imaged different clouds of atoms thousands of times and translated each image into a digitized version resembling a grid. Each grid showed the location of atoms of both types (depicted as red versus blue in their paper). From these maps, they were able to see squares in the grid with either a lone red or blue atom, and squares where both a red and blue atom paired up locally (depicted as white), as well as empty squares that contained neither a red or blue atom (black).

Already individual images show many local pairs, and red and blue atoms in close proximity. By analyzing sets of hundred of images, the team could show that atoms indeed show up in pairs, at times linking up in a tight pair within one square, and at other times forming looser pairs, separated by one or several grid spacings. This physical separation, or “nonlocal pairing,” was predicted by the Hubbard model but never directly observed.

The researchers also observed that collections of pairs seemed to form a broader, checkerboard pattern, and that this pattern wobbled in and out of formation as one partner of a pair ventured outside its square and momentarily distorted the checkerboard of other pairings. This phenomenon, known as a “polaron,” was also predicted but never seen directly.

“In this dynamic soup, the particles are constantly hopping on top of each other, moving away, but never dancing too far from each other,” Zwierlein notes.

The pairing behavior between these atoms must also occur in superconducting electrons, and Zwierlein says the team’s new snapshots will help to inform scientists’ understanding of high-temperature superconductors, and perhaps provide insight into how these materials might be tuned to higher, more practical temperatures.

“If you normalize our gas of atoms to the density of electrons in a metal, we think this pairing behavior should occur far above room temperature,” Zwierlein offers. “That gives a lot of hope and confidence that such pairing phenomena can in principle occur at elevated temperatures, and there’s no a priori limit to why there shouldn’t be a room-temperature superconductor one day.”

This research was supported, in part, by the U.S. National Science Foundation, the U.S. Air Force Office of Scientific Research, and the Vannevar Bush Faculty Fellowship.

###

Written by Jennifer Chu, MIT News Office

END

MIT physicists generate the first snapshots of fermion pairs

The images shed light on how electrons form superconducting pairs that glide through materials without friction.

2023-07-06

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Prize winner reveals how commensal-derived “silent” flagellins evade innate immunity

2023-07-06

Sara Clasen is the 2023 winner of the NOSTER & Science Microbiome Prize for her work in illuminating how “silent flagellins” from commensal microbiota evade a host’s innate immunity.

The NOSTER & Science Microbiome Prize aims to reward innovative research from young investigators working on the functional attributes of the microbiota of any organism that has potential to contribute to our understanding of health and disease, or to guide novel therapeutic interventions.

Strong adaptive immune responses require activation of innate immunity. To do this, innate ...

Researchers demonstrate first visible wavelength femtosecond fiber laser

2023-07-06

WASHINGTON — Researchers have developed the first fiber laser that can produce femtosecond pulses in the visible range of the electromagnetic spectrum. Fiber lasers producing ultrashort, bright visible-wavelength pulses could be useful for a variety of biomedical applications as well as other areas such as material processing.

Visible femtosecond pulses are usually obtained using complex and inherently inefficient setups. Although fiber lasers represent a very promising alternative due to their ruggedness/reliability, small footprint, efficiency, lower cost and high brightness, it hasn’t been possible, until now, to produce visible pulses with durations in the femtosecond ...

Top corn producing state to see future drop in yield, cover crop efficiency

2023-07-06

URBANA, Ill. — Winter cover crops could cut nitrogen pollution in Illinois’ agricultural drainage water up to 30%, according to recent research from the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. But how will future climate change affect nitrogen loss, and will cover crops still be up to the job? A new study investigating near- and far-term climate change in Illinois suggests cover crops will still be beneficial, but not to the same degree. The report also forecasts corn ...

New study: Black women with hypertensive disorders of pregnancy have increased stroke risk

2023-07-06

(Boston) – U.S. Black women have a disproportionately higher burden of both preeclamptic pregnancy and stroke compared with white women, but virtually all existing evidence on the association between the two medical conditions has come from studies of white women.

A newly published study focuses on data gathered over 25 years from 59,000 Black women in the Black Women’s Health Study (BWHS) and is led by researchers from Boston University Chobanian & Avedisian School of Medicine and Slone Epidemiology Center. The study, published in the New England Journal of Medicine Evidence, ...

Bezos Earth Fund grants $12 million to Smithsonian to support major forest carbon project

2023-07-06

By conserving and replanting forests, the world buys time until it brings other climate and sustainability solutions online. As a critical step toward this goal, the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute (STRI) received a $12 million grant from the Bezos Earth Fund to support GEO-TREES. This international consortium is the first worldwide system to independently ensure the accuracy of satellite monitoring of forest biomass—a way to measure carbon stored in trees—in all forest types and conditions. The GEO-TREES alliance offers a freely accessible database that integrates ...

Legends of Norse Settlers drove Denmark towards Greenland

2023-07-06

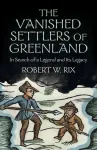

In 985, Viking explorer Erik the Red led a group of Icelandic farmers to Greenland, where they established a settlement on the west coast. Archaeological evidence suggests that the settlement existed for over 400 years, but the impact of the settlement lasted much longer. It is little recognised today that the hope of finding the descendants of the settlers dominated European and American perspectives on Greenland for centuries

In his new book The Vanished Settlers of Greenland: In Search of a Legend and Its Legacy, Associate Professor Robert Rix argues that the lost Norse settlement played a decisive ...

Archaeology: The power of the Copper Age 'Ivory Lady' revealed

2023-07-06

The highest status individual in ancient Copper Age society in Iberia, was a woman and not a man as previously thought, according to peptide analysis reported in Scientific Reports. The individual, now re-dubbed the 'Ivory Lady', was buried in a tomb filled with the largest collection of rare and valuable items in the region, including ivory tusks, high-quality flint, ostrich eggshell, amber, and a rock crystal dagger. These findings reveal the high status women could hold in this ancient society.

In 2008, an individual was discovered in a tomb in Valencia, Spain dating to the Copper Age between 3,200 and 2,200 years ago. As well as being a rare example of a single occupancy ...

Schizophrenia is associated with somatic mutations occurring in utero

2023-07-06

As a psychiatric disorder with onset in adulthood, schizophrenia is thought to be triggered by some combination of environmental factors and genetics, although the exact cause is still not fully understood. In a study published in the journal Cell Genomics on July 6, researchers find a correlation between schizophrenia and somatic copy-number variants, a type of mutation that occurs early in development but after genetic material is inherited. This study is one of the first to rigorously describe the relationship between somatic—not inherited—genetic mutations and schizophrenia risk.

“We originally thought of genetics as the study of inheritance. But now we ...

Team develops all-species coronavirus test

2023-07-06

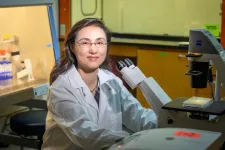

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. — In an advance that will help scientists track coronavirus variants in wild and domesticated animals, researchers report they can now detect exposure to the SARS-CoV-2 virus in any animal species. Most coronavirus antibody tests require specialized chemical reagents to detect host antibody responses against the virus in each species tested, impeding research across species.

The virus that causes COVID-19 in humans also infects a variety of animals, said University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign pathobiology professor and virologist Ying Fang, who led the new research. So far, ...

Shrinking Arctic glaciers are unearthing a new source of methane

2023-07-06

As the Arctic warms, shrinking glaciers are exposing bubbling groundwater springs which could provide an underestimated source of the potent greenhouse gas methane, finds new research published today in Nature Geoscience.

The study, led by researchers from the University of Cambridge and the University Centre in Svalbard, Norway, identified large stocks of methane gas leaking from groundwater springs unveiled by melting glaciers.

The research suggests that these methane emissions will likely increase as Arctic glaciers retreat and more ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

First degree female relatives’ suicidal intentions may influence women’s suicide risk

Specific gut bacteria species (R inulinivorans) linked to muscle strength

Wegovy may have highest ‘eye stroke’ and sight loss risk of semaglutide GLP-1 agonists

New African species confirms evolutionary origin of magic mushrooms

Mining the dark transcriptome: University of Toronto Engineering researchers create the first potential drug molecules from long noncoding RNA

IU researchers identify clotting protein as potential target in pancreatic cancer

Human moral agency irreplaceable in the era of artificial intelligence

Racial, political cues on social media shape TV audiences’ choices

New model offers ‘clear path’ to keeping clean water flowing in rural Africa

Ochsner MD Anderson to be first in the southern U.S. to offer precision cancer radiation treatment

Newly transferred jumping genes drive lethal mutations

Where wells run deep, biodiversity runs thin

Q&A: Gassing up bioengineered materials for wound healing

From genetics to AI: Integrated approaches to decoding human language in the brain

Leora Westbrook appointed executive director of NR2F1 Foundation

Massive-scale spatial multiplexing with 3D-printed photonic lanterns achieved by researchers

Younger stroke survivors face greater concentration, mental health challenges — especially those not employed

From chatbots to assembly lines: the impact of AI on workplace safety

Low testosterone levels may be associated with increased risk of prostate cancer progression during surveillance

Analysis of ancient parrot DNA reveals sophisticated, long-distance animal trade network that pre-dates the Inca Empire

How does snow gather on a roof?

Modeling how pollen flows through urban areas

Blood test predicts dementia in women as many as 25 years before symptoms begin

Female reproductive cancers and the sex gap in survival

GLP-1RA switching and treatment persistence in adults without diabetes

Gnaw-y by nature: Researchers discover neural circuit that rewards gnawing behavior in rodents

Research alert: How one receptor can help — or hurt — your blood vessels

Lamprey-inspired amphibious suction disc with hybrid adhesion mechanism

A domain generalization method for EEG based on domain-invariant feature and data augmentation

Bionic wearable ECG with multimodal large language models: coherent temporal modeling for early ischemia warning and reperfusion risk stratification

[Press-News.org] MIT physicists generate the first snapshots of fermion pairsThe images shed light on how electrons form superconducting pairs that glide through materials without friction.