(Press-News.org) MISSOULA – While humans sheltered in place during the COVID-19 pandemic, wild animals took the opportunity to roam spaces typically avoided by wildlife, according to a study published last month in Science. Photos quickly emerged of wild goats spotted on the city streets of Wales and coyotes touring downtown San Francisco, yet evidence explaining this phenomenon was sparse.

Dr. Mark Hebblewhite, professor of ungulate habitat ecology at the University of Montana, joined an international research team of 175, led by Dr. Marlee Tucker – an ecologist at Radboud University in the Netherlands – in analyzing global data from 2,300 land mammals from around the world tracked by GPS devices.

In locations with strict lockdown policies, animals (from elephants to giraffes to bears and deer) traveled longer distances during the lockdown period. In highly populated areas, mammals moved less frequently and were closer to roads than they were before the pandemic. These results demonstrate how human activities constrain animal movement and what happens when those activities cease.

“The fact that human activity is affecting wildlife on a day-to-day basis across the planet is not new,” said Hebblewhite, who works in the W.A. Franke College of Forestry and Conservation. “But this study exemplifies the global impact human activity has on wildlife everywhere.”

Researchers tracked data from 43 different species of mammals, Hebblewhite said. Surprisingly, the biggest variation in the study was really driven by variation in human lockdowns.

What about Montana? A place where land mammals have the luxury of miles and miles of wild spaces and where humans flocked to escape the lockdown measures in bigger cities?

While some states and countries, such as Europe, had more stringent lockdown requirements – researchers called this the COVID lockdown stringency index – the effects were different in Montana, where there was an increase in human activity in open spaces around cities like Missoula.

“But even in places like Montana and the Western U.S., we saw changes in human behavior,” Hebblewhite said. “People drove less, and there was less human activity at the typical times of day we see animals and humans being active.”

While researchers were able to understand animal behavior during the pandemic by studying the GPS data of 3,200 collared species, they didn’t have comparably detailed data about human responses.

“What is it about humans? What do we mean by human activity?” Hebblewhite said. “Humans build infrastructure: highways, railways, golf courses, trails. It’s the physical footprint of human development – the human footprint index.”

During COVID, that footprint didn’t change, but the amount of people on it did.

Researchers discovered three different wildlife responses to the worldwide lockdown:

On average, animals moved every hour less than prior to lockdown measures because they no longer had to avoid humans as much on a daily basis. Humans are predictably busier on roads, trails and highways in the mornings before 9 a.m. and the evenings after 5 p.m. In California, for example, mountain lions didn’t have to avoid urban areas as much because there was less human activity.

Animal migration increased. Researchers found that animals made long-distance movements more frequently. While on sabbatical in Italy, Hebblewhite studied European brown bears and predicted where the bears might cross highways in connectivity corridors. “Bears during COVID increased long-distance movements in those corridors as we predicted,” he said. “Moving between valleys, dispersing, migrating – those things did increase when human activity decreased. They didn’t have to avoid humans and could make riskier movements.” During the pandemic, bears in Italy used corridors they had never used before because humans were locked in their homes.

Animals were found closer to roads and in areas heavily used by humans. “Our interpretation is consistent with the first piece on hourly movements. People were no longer driving on roads and highway traffic was down. The roadway was still there, but animals were no longer afraid of it. They moved closer to highways and railways and began crossing them more during the day rather than at night,” he said. Researchers found this to be the case across the planet and among all 43 species.

“This is a global analysis of 2.5 thousand GPS animals across 43 species. The result is strong,” Hebblewhite said. “As strong as you can get in science with animals.”

The study supports the assumption that human activity has profound impacts on animals across the planet, and its impact was recently demonstrated after last summer’s flooding in Yellowstone. The event caused humans to once again shelter in place and cease activity in the busy national park. The results from the study allowed researchers and park managers to make exact predictions of wildlife behavior during that time.

“In Banff, based on studies like this, the national park closed down Highway 1A in the spring when wildlife is restricted to lower elevations,” Hebblewhite said. “They closed the highway because previous studies like this showed negative effects of human activity on wildlife during that time of year.”

In Montana, the study could support road closures during elk hunting season in order to increase elk survival and have more bull elk for harvesting, he adds.

“Now, we can look at this and think of human-restricted activity in order to help people managing elephant activity in Africa,” Hebblewhite said. “It’s a strong paper that demonstrates the global effect of humans on wildlife. It illustrates the impacts of human activities even in our most protected national parks. Anyone who goes to Yellowstone in summer spends most of the time thinking about how to avoid traffic. If you’re thinking about it, then wildlife is thinking about it too.”

END

Global study finds while humans sheltered in place, wildlife roamed

2023-07-10

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Curious compound: Tin selenide may hold the key for thermoelectric solutions

2023-07-10

Researchers at the FAMU-FSU College of Engineering and the National High Magnetic Field Laboratory discovered that atomic-level structural changes occur when the compound tin selenide heats up — changes that help it to conduct electricity but not heat.

The study, funded by the National Science Foundation and Department of Energy, provides information that could lead to new technologies for applications such as refrigeration or waste heat recovery from cars or nuclear power plants. The research was published by Nature Communications.

“Tin selenide is a curious compound,” ...

Massachusetts drinking water may contain unsafe levels of manganese

2023-07-10

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

Contact:

Jillian McKoy, jpmckoy@bu.edu

Michael Saunders, msaunder@bu.edu

##

Massachusetts Drinking Water May Contain Unsafe Levels of Manganese

A new study measured manganese levels in the residential tap water of a Holliston, Mass. community and found that the manganese concentrations occasionally exceeded the maximum safety level recommended in state and federal guidelines.

Manganese is ...

Scientists discover 36-million-year geological cycle that drives biodiversity

2023-07-10

Movement in the Earth’s tectonic plates indirectly triggers bursts of biodiversity in 36‑million-year cycles by forcing sea levels to rise and fall, new research has shown.

Researchers including geoscientists at the University of Sydney believe these geologically driven cycles of sea level changes have a significant impact on the diversity of marine species, going back at least 250 million years.

As water levels rise and fall, different habitats on the continental shelves and in shallow seas expand and contract, ...

The sound of silence? Researchers prove people hear it

2023-07-10

Silence might not be deafening but it’s something that literally can be heard, concludes a team of philosophers and psychologists who used auditory illusions to reveal how moments of silence distort people’s perception of time.

The findings address the debate of whether people can hear more than sounds, which has puzzled philosophers for centuries.

“We typically think of our sense of hearing as being concerned with sounds. But silence, whatever it is, is not a sound — it’s the absence of sound,” said lead author Rui Zhe Goh, a Johns Hopkins University graduate student in philosophy and psychology. “Surprisingly, ...

Caterpillar venom study reveals toxins borrowed from bacteria

2023-07-10

Researchers at The University of Queensland have discovered the venom of a notorious caterpillar has a surprising ancestry and could be key to the delivery of lifesaving drugs.

A team led by Dr Andrew Walker and Professor Glenn King from UQ’s Institute for Molecular Bioscience found toxins in the venom of asp caterpillars punch holes in cells the same way as toxins produced by disease-causing bacteria such as E. coli and Salmonella.

“We were surprised to find asp caterpillar venom was completely ...

Global cooling caused diversity of species in orchids, confirms study

2023-07-10

Research led by the Milner Centre for Evolution at the University of Bath looking at the evolution of terrestrial orchid species has found that global cooling of the climate appears to be the major driving factor in their diversity. The results help scientists understand the role of global climate on diversity of species, and how our current changing global climate might affect biodiversity in the future.

One of the largest families of plants, there are around 28,000 species of orchids growing across the world. These plants are known for their huge variety of different sized and shaped flowers, so why are there so many species

Climate change driving speciation

Charles ...

Real-world context increases capacity for remembering colors

2023-07-10

Human memory is fundamental to everything we do. From remembering the faces of someone you just met to finding your cell phone that you just left on a table, one's "visual working memory"— the core cognitive system that retains visual information in an active state for a short period of time, plays a vital role. Prior work has found that visual working memory capacity is well correlated with other important cognitive abilities such as academic performance, and fluid intelligence, which includes general reasoning and problem solving, so understanding its limits is integral to understanding how human cognition works.

In the past, theories have proposed that an individual’s ...

Argonne scientist Shirley Meng recognized for contributions to battery science

2023-07-10

The Electrochemical Society (ECS) has selected scientist Shirley Meng of the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE) Argonne National Laboratory as the recipient of the 2023 Battery Division Research Award for innovative research on interfacial science, which has led to improved battery technologies.

A pioneer in discovering and designing better materials for energy storage, Meng serves as chief scientist of the Argonne Collaborative Center for Energy Storage Science (ACCESS) and as a professor at the Pritzker School of Molecular ...

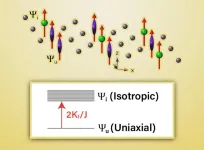

Researchers make a surprising discovery about the magnetic interactions in a Kagome layered topological magnet

2023-07-10

A team from Ames National Laboratory conducted an in-depth investigation of the magnetism of TbMn6Sn6, a Kagome layered topological magnet. They were surprised to find that the magnetic spin reorientation in TbMn6Sn6 occurs by generating increasing numbers of magnetically isotropic ions as the temperature increases.

Rob McQueeney, a scientist at Ames Lab and project lead, explained that TbMn6Sn6has two different magnetic ions in the material, terbium and manganese. The direction of the manganese moments controls the topological state, “But ...

Deciphering progesterone’s mechanisms of action in breast cancer

2023-07-10

“The mechanisms underlying the observed effects of progesterone on breast cancer outcomes are unclear.”

BUFFALO, NY- July 10, 2023 – A new research perspective was published in Oncotarget's Volume 14 on July 1, 2023, entitled, “Deciphering the mechanisms of action of progesterone in breast cancer.”

A practice-changing, randomized, controlled clinical study established that preoperative hydroxyprogesterone administration improves disease-free and overall survival in patients with node-positive breast cancer. In this new perspective, researchers Gaurav Chakravorty, Suhail Ahmad, Mukul S. Godbole, Sudeep Gupta, Rajendra A. Badwe, ...