(Press-News.org) In Africa, climate change impacts are experienced as extreme events like drought and floods. Through the Famine Early Warning Systems Network (which leverages expertise from USG science agencies, universities, and the private sector) and the IGAD Climate Prediction and Applications Center, it has been possible to predict and monitor these climatic events, providing early warning of their impacts on agriculture to support humanitarian and resilience programming in the most food insecure countries of the world.

Science is beginning to catch up with and even get ahead of climate change. In a commentary for the journal Earth’s Future, UC Santa Barbara climate scientist Chris Funk and co-authors assert that predicting the droughts that cause severe food insecurity in the Eastern Horn of Africa (Kenya, Somalia and Ethiopia) is now possible, with months-long lead times that allow for measures to be taken that can help millions of the region’s farmers and pastoralists prepare for and adapt to the lean seasons.

“We’ve gotten very good at making these predictions,” said Funk, who directs UCSB’s Climate Hazards Center, a multidisciplinary alliance of scientists who work to predict droughts and food shortages in vulnerable areas.

In the summer of 2020, the CHC predicted that climate change, interacting with naturally occurring La Niña events, would bring devastating sequential drought to the Eastern Horn of Africa. The region normally has two wet seasons a year — spring and fall. An unprecedented five rainy seasons in a row failed. Eight months before each of those failures, the CHC anticipated droughts. Fortunately, agencies and other collaborators paid heed to those early warnings and were able to take effective actions, Funk said. Within the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), the forecasts helped motivate hundreds of millions of dollars in assistance for millions of starving people.

These efforts were a far cry from similar predictions of sequential droughts that the researchers, collaborating with the USAID-supported Famine Early Warning Systems Network, made for the same region ten years earlier. Predictions that went largely unheeded. “More than 250,000 Somalis died,” Funk said. “It was just really horrible.”

At the time, he said, the available forecasts weren’t able to predict rainfall deficits in this region. While the models said East Africa would become wetter, observations showed substantial declines in the spring wet season. And to be fair, he added, the group’s long-range weather prediction capabilities were still in their infancy. “We made an accurate forecast, but we didn’t understand very well what was going on scientifically,” Funk said. “Now, following our success in 2016/17, and extensive outreach efforts, the humanitarian relief community appreciates the value of our early warning systems.”

In the intervening 10 years, the researchers have worked to discern and understand the broad, often distant mechanisms that drive drought in the Eastern Horn of Africa and create accurate, tailored forecasts for the region. They built on research showing that increased rainfall around Indonesia, caused by anthropogenic increases in sea surface temperatures, resulted in less moisture flowing on to the East African coast during the rainy months. These changes in moisture flows drive back-to-back droughts. But as climate change increases western Pacific sea surface temperatures, it becomes more and more possible to predict devastating water shortages.

“We’ve published about 15 scientific papers on this topic,” Funk said, “and we’ve forecasted dry seasons in 2016-2017, which helped prevent a famine that year.” As he discusses in his book “Drought, Flood, Fire (Cambridge University Press, 2021),” “climate change amplifies natural sea surface temperature variations, which opens the door to better forecasts.”

In the new commentary and a longer paper currently at preprint stage, also coming out in Earth’s Future, the co-authors highlight, respectively, the opportunities associated with these long range outlooks, and the physical mechanisms explaining the predictability.

“To reduce the impacts of climate extremes, we need to look for opportunities,” said CHC Specialist and Operations Analyst Laura Harrison. “We need to pay attention to not just how climate is changing, but how these changes can support more effective predictions for droughts and for advantageous cropping conditions. As a community, we also need to foster communication about successful resilience strategies.”

"Flooding still happens, drought still happens, people still get hurt, but we can try to reduce the harm."

With climate models that can predict extreme ocean states at eight-month lead times, and weather forecasts that can make projections at two weeks and at 45 days, CHC scientists and researchers now can provide actionable information to collaborators on the ground to help local farmers anticipate and plan for dry conditions.

“We’re working with this group called Plant Village, who is providing agricultural advisories to millions of Kenyans, and helping them take actions that can help make their crops more drought-resistant,” Funk said.

This proactivity is something Funk and collaborators hope will become a bigger part of climate change strategy for the Eastern Horn of Africa, as their models predict more of these drought-forming conditions in the region’s future. A better local understanding of the mechanisms that result in droughts, and investments in early warning systems and adaptation measures, may initially be costly, they said, “but are relatively inexpensive when compared to post-impact, response-based alternatives such as humanitarian assistance and/or funding safety-net programs.”

Education and participation can build trust and ultimately increase resilience. The CHC is building on what they learned in East Africa, and using it to feed partnerships in other parts of the world. In southern Africa, for example, they are collaborating with the Zimbabwe Meteorological Services Department and the Knowledge Impact Network to support the development of actionable climate services.

“Understanding that climate change makes extremes more frequent is really empowering because now we can try to anticipate those bad effects,” Funk said. “Flooding still happens, drought still happens, people still get hurt, but we can try to reduce the harm.”

END

Climate science is catching up to climate change with predictions that could improve proactive response

2023-07-20

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Detecting threats beyond the limits of human, sensor sight

2023-07-20

ALBUQUERQUE, N.M. — Remember what it’s like to twirl a sparkler on a summer night? Hold it still and the fire crackles and sparks but twirl it around and the light blurs into a line tracing each whirl and jag you make.

A new patented software system developed at Sandia National Laboratories can find the curves of motion in streaming video and images from satellites, drones and far-range security cameras and turn them into signals to find and track moving objects as small as one pixel. The developers say this system can enhance the performance of any remote sensing application.

“Being able to track each pixel from a distance matters, ...

Nature inspires breakthrough achievement: hazard-free production of fluorochemicals

2023-07-20

For the first time, Oxford chemists have generated fluorochemicals – critical for many industries – without the use of hazardous hydrogen fluoride gas.

The innovative method was inspired by the biomineralization process that forms our teeth and bones.

The results are published today in the leading journal Science.

A team of chemists have developed an entirely new method for generating critically important fluorochemicals that bypasses the hazardous product hydrogen fluoride (HF) gas. ...

Could early induction of labor reduce inequities in pregnancy outcomes?

2023-07-20

Inducing labor at 39 weeks of pregnancy has the greatest benefit in risk reduction for women from more socioeconomically deprived areas, according to a new study published July 13th in the open access journal PLOS Medicine by Ipek Gurol-Urganci of the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, UK, and colleagues. The findings suggest that increased uptake of induction of labor at 39 weeks may help reduce inequities in adverse perinatal outcomes.

Adverse perinatal outcomes— which include stillbirths, neonatal ...

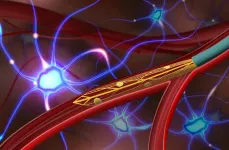

Ultra-flexible endovascular probe records deep-brain activity in rats, without surgery

2023-07-20

A new ultra-small and ultra-flexible electronic neural implant, delivered via blood vessels, can record single-neuron activity deep within the brains of rats, according to new study. “This technology could enable long-term, minimally invasive bioelectronic interfaces with deep-brain regions, writes Brian Timko in a related Perspective. Brain-machine interfaces (BMIs) enable direct electrical communication between the brain and external electronic systems. They allow brain activity to directly ...

Northwestern Greenland was ice-free 400,000 years ago, according to Camp Century sediments

2023-07-20

Sediments recovered from the base of the Camp Century ice core show that northwestern Greenland was ice-free during a period of history known to have exhibited some of the lowest global ice volumes -- the Marine Isotope Stage (MIS) 11 interglacial period. The absence of ice at that location means that the Greenland Ice Sheet must have contributed more 1.4 meters of sea-level equivalent to global sea level during the interglacial – a period in which average global air temperature was similar to what we’ll soon experience, given human-caused climate warming. The climate conditions of past interglacials – periods during Earth’s climatic history ...

Global GPS measurements indicate observable phase of fault slip two hours before large earthquakes

2023-07-20

Analysis of Global Positioning System (GPS) time-series data from nearly 100 large earthquakes worldwide has provided evidence for the existence of a precursory phase of fault slip occurring two hours before seismic rupture. “If it can be confirmed that earthquake nucleation often involves an hours-long precursory phase, and the means can be developed to reliably measure it, a precursor warning could be issued,” writes Roland Bürgmann in a related Perspective. The ability to predict large earthquakes has been a longstanding yet elusive goal. Short-term ...

Biobank-scale imaging data unveils the genetic architecture of the human skeletal form

2023-07-20

Combining data from full-body x-ray images and associated genomic data from more than 30,000 UK Biobank participants, researchers have helped illuminate the genetic basis of human skeletal proportions. The findings not only provide new insights into the evolution of the human skeletal form and its role in musculoskeletal disease, but they also demonstrate the utility of using population-scale imaging data from biobanks to understand both disease-related and normal physical variation among humans. Of all primates, humans are the only ones to have evolved to be normally bipedal, an adaptation that may have facilitated the use of tools and accelerated cognitive development. ...

Genes that shape bones identified, offering clues about our past and future

2023-07-20

Using artificial intelligence to analyze tens of thousands of X-ray images and genetic sequences, researchers from The University of Texas at Austin and New York Genome Center have been able to pinpoint the genes that shape our skeletons, from the width of our shoulders to the length of our legs.

The research, published as the cover article in Science, pulls back a curtain on our evolutionary past and opens a window into a future where doctors can better predict patients’ risks of developing conditions such as back pain or arthritis in later life.

“Our research is a powerful demonstration of the impact of AI in medicine, particularly when it comes to analyzing ...

Immune systems develop ‘silver bullet’ defences against common bacteria

2023-07-20

Immune systems develop specific genes to combat common bacteria such as those found in food, new research shows.

Previous theories have suggested that antimicrobial peptides – a kind of natural antibiotics – have a general role in killing a range of bacteria.

However, the new study, published in Science, examined how the immune systems of fruit flies are shaped by the bacteria in their food and environment.

The researchers, from the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology and the University of Exeter, found two peptides that each control a single bacterial species commonly encountered by the flies.

“We know that an animal’s food and environment ...

These bones were made for walking

2023-07-20

NEW YORK, NY--Perhaps the most profound advance in primate evolution occurred about 6 million years ago when our ancestors started walking on two legs. The gradual shift to bipedal locomotion is thought to have made primates more adaptable to diverse environments and freed their hands to make use of tools, which in turn accelerated cognitive development. With those changes, the stage was set for modern humans.

The genetic changes that made possible the transition from knuckle-based scampering in great apes to upright walking in humans have now been uncovered in a new study by researchers ...