(Press-News.org)

Owing to human activities and climate change, many animal species have invaded new habitats. Such biological invasion comes with devastating impacts on the local biodiversity and ecosystems. The red swamp crayfish—known to the scientific world as Procambarus clarkii (P. clarkii)— is no exception. P. clarkii is a freshwater crayfish native to the tropical regions of southern USA and northeastern Mexico. After their introduction to different parts of the world, they have become one of the most widespread and invasive animal species. They are known for their adaptability and aggressive behavior that ensure their survival in a wide range of environments, even in regions much colder than their original habitats.

Given that P. clarkii is typically limited to subtropical climates, researchers have long endeavored to find a few P. clarkii populations in the colder regions of Japan. In Hokkaido, the northernmost island of Japan, P. clarkii populations have been observed in a limited number of rivers and ponds where water from hot springs or sewage treatment plants flows in and contributes to high water temperatures throughout the year. A recent report, however, describes some populations settled in Sapporo City of central Hokkaido, where water temperatures become extremely low during the winter. A group of researchers from Japan, including Dr. Daiki Sato, Assistant Professor in the Graduate School of Science of Chiba University, and Professor Takashi Makino from Tohoku University sought to study the genetic changes that have allowed the crayfish to adapt to these cold environments. Their study was made available online on July 3, 2023, and will be published in Volume 26, Issue 8 of the journal iScience on August 18, 2023. Their article was additionally selected and included in the journal’s special issue, “Invasion Dynamics.”

Speaking about the motivations behind their study, Prof. Makino, who led the study, says, “Although the red swamp crayfish has been a well-known and notorious invasive species in Japan for quite some time, nobody has examined its genomic and transcriptomic characteristics that contribute to its invasiveness yet, thus motivating us to pursue this study. We feel our study has far-reaching ecological implications.”

Accordingly, the researchers studied P. clarkii from different populations in the newly colonized Japan and the originally inhabited USA. They compared differences in cold tolerance and related genetic characteristics among the samples. They also studied the effects of natural selection by comparing changes in gene sequences among the samples.

When asked about the main findings of the study, Dr. Sato, the first and co-corresponding author of the study, exclaims, “A population of red swamp crayfish in Sapporo, Japan may have acquired genetic changes that enhanced its cold tolerance. We have revealed the genes and genomic architecture possibly involved in the cold adaptation mechanism.”

The researchers found that different P. clarkii populations, even within Japan, responded differently to the cold: some showed no significant changes in gene expression over time, while others displayed noticeable differences between the beginning and the end of the experiment.

Notably, they discovered regulatory changes in a group of genes involved in developing the protective outer layer of P. clarkii, called the cuticle. They also found an increase in the production of peptidase inhibitors—proteins that prevent the enzymatic degradation of proteins in the body. These peptidase inhibitors play a role in preserving protective proteins from being cold-damaged, thus contributing to cold resistance in P. clarkii.

Further, the researchers also found that some of the studied genes had undergone significant levels of duplication that resulted in a large number of copies of the same genes within the genome. This duplication may have amplified the genes’ functional abilities in dealing with low temperatures.

These results provide valuable insights into the molecular mechanisms adopted by invasive species to develop cold resistance and survive in cold habitats. When used in the right context, these findings could have potential medical applications.

Overall, these findings significantly contribute to our understanding of invasive species, which may help us take measures to prevent their spread and, in turn, protect global biodiversity.

About Assistant Professor Daiki Sato

Dr. Daiki Sato is an assistant professor at the Institute for Advanced Academic Research/Graduate School of Science, Chiba University. He works to unravel the molecular mechanisms and ecological functions underlying behavioral diversity in animals. His research interests include evolutionary genomics and behavioral ecology. He is a member of the Society for Evolutionary Studies, Japan, and The Ecological Society of Japan.

END

Breast cancer survival rates have improved considerably in the last few decades in Colombia, but factors that increase the likelihood of patients experiencing cardiovascular side effects, like cardiotoxicity, are not well-known or well-treated. A recent study in the North-East region of Colombia found 11.94% of patients with a high BMI being treated for breast cancer at a regional center experienced heart damage, or cardiotoxicity, during chemotherapy. The study will be presented at the American College of Cardiology (ACC) Latin America 2023 Together with Asociación Costarricense ...

AUSTIN, Texas – A new statistical tool can help researchers get meaningful results when a randomized experiment, considered the gold standard, is not possible.

Randomized experiments split participants into groups by chance, with one undergoing an intervention and the other not. But in real-world situations, they can’t always be done. Companies might not want to use the method, or such experiments might be against the law.

Developed by a researcher at The University of Texas at Austin, the new tool called two-step synthetic control adapts an existing research workaround, known as the synthetic control method.

The ...

The first-ever study to look at drivers of both marine heatwaves and cold spells in the shallow nearshore along the California Current —coordinated by California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo (Cal Poly) and the Virginia Institute of Marine Science, William & Mary — found that certain environmental conditions and the state of the ocean can lead to an enhanced risk for ocean temperature extremes.

The findings were recently published in Nature Scientific Reports in an article titled “Effects of basin-scale climate modes and upwelling on nearshore marine heatwaves and cold spells in the California Current.”

Extreme ...

Just as bacteria can develop antibiotic resistance, viruses can also evade drug treatments. Developing therapies against these microbes is difficult because viruses often mutate or hide themselves within cells. But by mimicking the way the immune system naturally deals with invaders, researchers reporting in ACS Infectious Diseases have developed a “peptoid” antiviral therapy that effectively inactivates three viruses in lab tests. The approach disrupts the microbes by targeting certain ...

Antiviral therapies are notoriously difficult to develop, as viruses can quickly mutate to become resistant to drugs. But what if a new generation of antivirals ignores the fast-mutating proteins on the surface of viruses and instead disrupts their protective layers?

“We found an Achilles heel of many viruses: their bubble-like membranes. Exploiting this vulnerability and disrupting the membrane is a promising mechanism of action for developing new antivirals,” said Kent Kirshenbaum, professor of chemistry at NYU and the study’s senior author.

In a new study ...

DALLAS, August 2, 2023 — The American Heart Association, a relentless force for a world of longer, healthier lives, has recognized 2,671 health care and emergency response organizations — nearly 145 more than in 2022 — for their commitment to improving health outcomes for cardiovascular patients through evidence-based efficient and coordinated care.

The American Heart Association’s Get With The Guidelines® and Mission: Lifeline® are hospital-based quality improvement recognition programs that use the latest evidence-based scientific guidelines to save lives and hasten health care recovery ...

With a survival rate in the single digits, pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) is highly lethal. In fact, by the time PDAC is clinically diagnosed, it is already considered incurable via surgery or other means in up to 90% of patients.

Yangzom D. Bhutia, D.V.M., Ph.D., from the Department of Cell Biology and Biochemistry at the Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center (TTUHSC) School of Medicine, has for years focused her research on PDAC. To bolster her efforts, the National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health recently awarded Bhutia a five-year, $1.76 million grant (“SLC6A14 as a unique ...

A sociological study by the University of Zurich confirms that a considerable proportion of employees perceive their work as socially useless. Employees in financial, sales and management occupations are more likely to conclude that their jobs are of little use to society.

In recent years, research showed that many professionals consider their work to be socially useless. Various explanations have been proposed for the phenomenon. The much-discussed “bullshit jobs theory” by the American anthropologist David Graeber, for example, states that some jobs are objectively useless and that this occurs more frequently ...

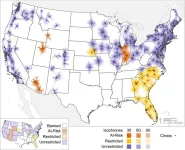

SPOKANE, Wash. – One year after the Dobbs decision, 41.8% of U.S. women of reproductive age have to drive 30 minutes or more to reach an abortion care facility, according to a study of data as of June 2, 2023. Researchers predicted that number would rise to 53.5% if other state bills under consideration are passed.

The study estimated longer drives as well, finding that 29.3% of women didn’t have access to a facility within a 60-minute drive and 23.6% lacked access even within a 90-minute drive. Those figures would jump to 45.6% ...

Adverse childhood experiences have impacts deep into old age, especially for those who experienced violence, and include both physical and cognitive impairments.

It’s known that a difficult childhood can lead to a host of health issues as a young or midlife adult, but now, for the first time, researchers at UC San Franciso have linked adverse experiences early in life to lifelong health consequences.

They found that older U.S. adults with a history of stressful or traumatic experiences as children were more likely to experience both physical and cognitive impairments in their senior years. Stressful childhood experiences could include exposure to ...