(Press-News.org) Pregnant people who gained more than the now-recommended amount of weight had a higher risk of death from heart disease or diabetes in the decades that followed, according to new analysis of 50 years of data published in The Lancet and led by researchers from the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania. The group studied a large national data set that stretched from when a person gave birth through the next five decades, assessing mortality rates to show the potential long-term effects of weight gain in pregnancy. Higher risk of death was found for all weight groups studied — including those defined as underweight, normal weight, or overweight prior to their pregnancies — but no increase in risk was uncovered among those who had been obese.

“We hope that this work leads to greater efforts to identify new, effective, and safe ways to support pregnant people in achieving a healthy weight gain,” said the study’s lead author, Stefanie Hinkle, PhD, an assistant professor of Epidemiology and Obstetrics and Gynecology at Penn. “We showed that gaining weight during pregnancy within the current guidelines may protect against possible negative impacts much later in life, and this builds upon evidence of the short-term benefits for both maternal health and the health of the baby.”

As in their previous work showing links between complications in pregnancy and higher death rates in the following years, Hinkle and her colleagues — who included members of Penn’s departments of Biostatistics, Epidemiology and Informatics, and Obstetrics and Gynecology, as well as the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development — examined data from the Collaborative Perinatal Project. This project catalogued data from a racially diverse cohort of people who gave birth in the 1950s or 1960s and linked their records to mortality data that ran through 2016, approximately 50 years later. The researchers analyzed information from more than 45,000 people that included their body mass indices (BMI), weight changes over pregnancy, and compared these data to modern recommendations. Those numbers were then linked first to deaths of any cause, then to deaths by cardiovascular- or diabetes-related causes.

Modern recommendations for weight gain during pregnancy were set in 2009 and are linked directly to a person’s weight at the start of their pregnancy. They range from 28 to 40 pounds for people considered “underweight” by BMI standards to 11 to 20 pounds for those considered “obese.” In the present day, almost half of those who are pregnant gain more weight than recommended.

Approximately 39 percent of the people in the cohort had died by 2016, and the death rate increased in correlation with pre-pregnancy BMI — those with the lowest BMI died at a lower rate than those with the highest BMI.

Among those who were “underweight” before pregnancy but gained more than the (now) recommended amount of weight, the risk of death related to heart disease climbed by 84 percent. Among those considered to be of “normal” weight before their pregnancy (which was roughly two-thirds of the cohort), all-cause mortality rose by nine percent when they gained more weight than recommended, with their risk of heart disease-related death climbing by 20 percent. Finally, those considered “overweight” had a 12 percent increased risk of dying if they gained more weight than is now recommended, with a 12 percent increase in their risk of diabetes-related death.

The study found no correlation between high weight gain during pregnancy and subsequent deaths among those in the obese range. While their study wasn’t designed to look into that specific point, Hinkle said that it’s possible this group’s already-elevated death rate could have had a bearing on this finding.

Weight gain during pregnancy doesn’t happen in a vacuum, as health care access, nutrition, and stress can all play a significant factor in it. But now that they have a better picture of the long-term risks associated with unhealthy gains, Hinkle and her colleagues hope to find more that will help address the issue.

“We are committed to delving deeper into the various factors that can affect pregnant individuals' ability to achieve healthy weight gain during pregnancy,” Hinkle said. “Our team is dedicated to exploring the social, structural, biological, and individual aspects that play a role in this process.”

This study was funded by the Intramural Research Program of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institutes of Child Health and Human Development.

Pregnant people who gained more than the now-recommended amount of weight had a higher risk of death from heart disease or diabetes in the decades that followed, according to new analysis of 50 years of data published in The Lancet and led by researchers from the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania. The group studied a large national data set that stretched from when a person gave birth through the next five decades, assessing mortality rates to show the potential long-term effects of weight gain in pregnancy. Higher risk of death was found for all weight groups studied — including those defined as underweight, normal weight, or overweight prior to their pregnancies — but no increase in risk was uncovered among those who had been obese.

“We hope that this work leads to greater efforts to identify new, effective, and safe ways to support pregnant people in achieving a healthy weight gain,” said the study’s lead author, Stefanie Hinkle, PhD, an assistant professor of Epidemiology and Obstetrics and Gynecology at Penn. “We showed that gaining weight during pregnancy within the current guidelines may protect against possible negative impacts much later in life, and this builds upon evidence of the short-term benefits for both maternal health and the health of the baby.”

As in their previous work showing links between complications in pregnancy and higher death rates in the following years, Hinkle and her colleagues — who included members of Penn’s departments of Biostatistics, Epidemiology and Informatics, and Obstetrics and Gynecology, as well as the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development — examined data from the Collaborative Perinatal Project. This project catalogued data from a racially diverse cohort of people who gave birth in the 1950s or 1960s and linked their records to mortality data that ran through 2016, approximately 50 years later. The researchers analyzed information from more than 45,000 people that included their body mass indices (BMI), weight changes over pregnancy, and compared these data to modern recommendations. Those numbers were then linked first to deaths of any cause, then to deaths by cardiovascular- or diabetes-related causes.

Modern recommendations for weight gain during pregnancy were set in 2009 and are linked directly to a person’s weight at the start of their pregnancy. They range from 28 to 40 pounds for people considered “underweight” by BMI standards to 11 to 20 pounds for those considered “obese.” In the present day, almost half of those who are pregnant gain more weight than recommended.

Approximately 39 percent of the people in the cohort had died by 2016, and the death rate increased in correlation with pre-pregnancy BMI — those with the lowest BMI died at a lower rate than those with the highest BMI.

Among those who were “underweight” before pregnancy but gained more than the (now) recommended amount of weight, the risk of death related to heart disease climbed by 84 percent. Among those considered to be of “normal” weight before their pregnancy (which was roughly two-thirds of the cohort), all-cause mortality rose by nine percent when they gained more weight than recommended, with their risk of heart disease-related death climbing by 20 percent. Finally, those considered “overweight” had a 12 percent increased risk of dying if they gained more weight than is now recommended, with a 12 percent increase in their risk of diabetes-related death.

The study found no correlation between high weight gain during pregnancy and subsequent deaths among those in the obese range. While their study wasn’t designed to look into that specific point, Hinkle said that it’s possible this group’s already-elevated death rate could have had a bearing on this finding.

Weight gain during pregnancy doesn’t happen in a vacuum, as health care access, nutrition, and stress can all play a significant factor in it. But now that they have a better picture of the long-term risks associated with unhealthy gains, Hinkle and her colleagues hope to find more that will help address the issue.

“We are committed to delving deeper into the various factors that can affect pregnant individuals' ability to achieve healthy weight gain during pregnancy,” Hinkle said. “Our team is dedicated to exploring the social, structural, biological, and individual aspects that play a role in this process.”

This study was funded by the Intramural Research Program of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institutes of Child Health and Human Development.

Pregnant people who gained more than the now-recommended amount of weight had a higher risk of death from heart disease or diabetes in the decades that followed, according to new analysis of 50 years of data published in The Lancet and led by researchers from the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania. The group studied a large national data set that stretched from when a person gave birth through the next five decades, assessing mortality rates to show the potential long-term effects of weight gain in pregnancy. Higher risk of death was found for all weight groups studied — including those defined as underweight, normal weight, or overweight prior to their pregnancies — but no increase in risk was uncovered among those who had been obese.

“We hope that this work leads to greater efforts to identify new, effective, and safe ways to support pregnant people in achieving a healthy weight gain,” said the study’s lead author, Stefanie Hinkle, PhD, an assistant professor of Epidemiology and Obstetrics and Gynecology at Penn. “We showed that gaining weight during pregnancy within the current guidelines may protect against possible negative impacts much later in life, and this builds upon evidence of the short-term benefits for both maternal health and the health of the baby.”

As in their previous work showing links between complications in pregnancy and higher death rates in the following years, Hinkle and her colleagues — who included members of Penn’s departments of Biostatistics, Epidemiology and Informatics, and Obstetrics and Gynecology, as well as the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development — examined data from the Collaborative Perinatal Project. This project catalogued data from a racially diverse cohort of people who gave birth in the 1950s or 1960s and linked their records to mortality data that ran through 2016, approximately 50 years later. The researchers analyzed information from more than 45,000 people that included their body mass indices (BMI), weight changes over pregnancy, and compared these data to modern recommendations. Those numbers were then linked first to deaths of any cause, then to deaths by cardiovascular- or diabetes-related causes.

Modern recommendations for weight gain during pregnancy were set in 2009 and are linked directly to a person’s weight at the start of their pregnancy. They range from 28 to 40 pounds for people considered “underweight” by BMI standards to 11 to 20 pounds for those considered “obese.” In the present day, almost half of those who are pregnant gain more weight than recommended.

Approximately 39 percent of the people in the cohort had died by 2016, and the death rate increased in correlation with pre-pregnancy BMI — those with the lowest BMI died at a lower rate than those with the highest BMI.

Among those who were “underweight” before pregnancy but gained more than the (now) recommended amount of weight, the risk of death related to heart disease climbed by 84 percent. Among those considered to be of “normal” weight before their pregnancy (which was roughly two-thirds of the cohort), all-cause mortality rose by nine percent when they gained more weight than recommended, with their risk of heart disease-related death climbing by 20 percent. Finally, those considered “overweight” had a 12 percent increased risk of dying if they gained more weight than is now recommended, with a 12 percent increase in their risk of diabetes-related death.

The study found no correlation between high weight gain during pregnancy and subsequent deaths among those in the obese range. While their study wasn’t designed to look into that specific point, Hinkle said that it’s possible this group’s already-elevated death rate could have had a bearing on this finding.

Weight gain during pregnancy doesn’t happen in a vacuum, as health care access, nutrition, and stress can all play a significant factor in it. But now that they have a better picture of the long-term risks associated with unhealthy gains, Hinkle and her colleagues hope to find more that will help address the issue.

“We are committed to delving deeper into the various factors that can affect pregnant individuals' ability to achieve healthy weight gain during pregnancy,” Hinkle said. “Our team is dedicated to exploring the social, structural, biological, and individual aspects that play a role in this process.”

This study was funded by the Intramural Research Program of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institutes of Child Health and Human Development.

END

High pregnancy weight gain tied to higher risk of death in the following decades

2023-10-20

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

First-of-its kind hormone replacement treatment shows promise in patient trials

2023-10-20

A first-of-its kind hormone replacement therapy that more closely replicates the natural circadian and ultradian rhythms of our hormones has shown to improve symptoms in patients with adrenal conditions. Results from the University of Bristol-led clinical trial are published today [20 October] in the Journal of Internal Medicine.

Low levels of a key hormone called ‘cortisol’ is typically a result of conditions such as Addison's and Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia. The hormone regulates a range of vital processes, ...

For relationship maintenance, accurate perception of partner’s behavior is key

2023-10-19

URBANA, Ill. – Married couples and long-term romantic partners typically engage in a variety of behaviors that sustain and nourish the relationship. These actions promote higher levels of commitment, which benefits couples’ physical and psychological health. A new study from the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign looks at how such relationship maintenance behaviors interact with satisfaction and commitment.

“Relationship maintenance is a well-established measure of couple behavior. In our study, we measured it with five main categories, ...

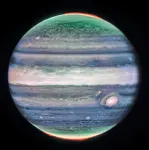

NASA's Webb discovers new feature in Jupiter’s atmosphere

2023-10-19

NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope has discovered a new, never-before-seen feature in Jupiter’s atmosphere. The high-speed jet stream, which spans more than 3,000 miles (4,800 kilometers) wide, sits over Jupiter’s equator above the main cloud decks. The discovery of this jet is giving insights into how the layers of Jupiter’s famously turbulent atmosphere interact with each other, and how Webb is uniquely capable of tracking those features.

“This is something that totally surprised us,” said Ricardo Hueso of the University of the Basque Country in Bilbao, Spain, lead author on the paper ...

MD Anderson research highlights: ESMO 2023 special edition

2023-10-19

ABSTRACTS: LBA71, 1088MO, 95MO, LBA48, 1082O, 1085O, LBA34, 243MO

MADRID ― The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center’s Research Highlights provides a glimpse into recent basic, translational and clinical cancer research from MD Anderson experts.

This special edition features upcoming oral presentations by MD Anderson researchers at the 2023 European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) Congress focused on clinical advances across a variety of cancer types. Highlights include a combination strategy for EGFR-mutant metastatic lung cancer, updated results for a Phase ...

To excel at engineering design, generative AI must learn to innovate, study finds

2023-10-19

ChatGPT and other deep generative models are proving to be uncanny mimics. These AI supermodels can churn out poems, finish symphonies, and create new videos and images by automatically learning from millions of examples of previous works. These enormously powerful and versatile tools excel at generating new content that resembles everything they’ve seen before.

But as MIT engineers say in a new study, similarity isn’t enough if you want to truly innovate in engineering tasks.

“Deep generative models (DGMs) are ...

Startup workers flee for bigger, more established companies during pandemic

2023-10-19

October 19, 2023

Startup workers flee for bigger, more established companies during pandemic

Findings reveal vulnerability of early-stage firms in downturns

Toronto - The world may have felt like it had stopped in the pandemic’s first weeks. But a “flight to safety” was underway at a popular digital job platform catering to the startup sector.

Digging into the data for nearly 180,000 users from AngelList Talent (now called Wellfound), the biggest online recruitment platform for private and entrepreneurial companies, researchers have found that U.S. job hunters turned away from smaller, early-stage companies in favour of positions at bigger, more established firms.

Just ...

Research repository arXiv receives $10M for upgrades

2023-10-19

ITHACA, N.Y. -- Cornell Tech has announced a total of more than $10 million in gifts and grants from the Simons Foundation and the National Science Foundation, respectively, to support arXiv, a free distribution service and open-access archive for scholarly articles.

The funding will allow the growing repository with more than 2 million articles to migrate to the cloud and modernize its code to ensure reliability, fault tolerance and accessibility for researchers.

“I am deeply grateful for this tremendous support from both the Simons Foundation ...

Electrons are quick-change artists in molten salts, chemists show

2023-10-19

In a finding that helps elucidate how molten salts in advanced nuclear reactors might behave, scientists have shown how electrons interacting with the ions of the molten salt can form three states with different properties. Understanding these states can help predict the impact of radiation on the performance of salt-fueled reactors.

The researchers, from the Department of Energy’s Oak Ridge National Laboratory and the University of Iowa, computationally simulated the introduction of an excess electron into molten zinc chloride salt to see what would happen.

They found three possible scenarios. In one, the electron becomes part of a molecular radical that ...

Communities of color experienced fear and mistrust of institutions during COVID-19 pandemic

2023-10-19

RIVERSIDE, Calif. -- A study led by researchers in the School of Medicine at the University of California, Riverside, has found that in communities of color in Inland Southern California, historical, cultural, and social traumas induce fear and mistrust in public health and medical, scientific, and governmental institutions, which, in turn, influence these communities’ hesitation to get tested and vaccinated for COVID-19.

The study, published in Culture, Medicine, and Psychiatry, underscores the need for community-based health interventions that consider structural and social determinants of health ...

Nail salon and other small beauty service workers face significant daily health challenges

2023-10-19

The beauty service microbusiness industry in the United States — such as the small, independently-owned nail salons found across the country — is huge, with more than $62 billion in annual sales.

However, most of the workers who provide these highly sought services are Asian female immigrants who earn very low wages. These workers face numerous workplace health challenges stemming from the chemicals they use, repetitive movements with handheld tools and awkward body posturing.

They also are reluctant to bring attention to these conditions due to factors such as possible immigration-related trauma, lack of English proficiency, ...