(Press-News.org) Karl Klose, director of The South Texas Center for Emerging Infectious Diseases (STCEID) and the Robert J. Kleberg, Jr. and Helen C. Kleberg College of Sciences Endowed Professor, coauthored a research article with Cameron Lloyd ’23, a UTSA doctoral student who graduated in August with a Ph.D. in molecular microbiology and immunology under the guidance of Klose.

The research paper investigates a novel strategy for inhibiting the spread and infection of Vibrio cholerae, the bacteria responsible for the disease, cholera.

The research article is entitled, “A peptide-binding domain shared with an Antarctic bacterium facilitates Vibrio cholerae human cell binding and intestinal colonization" and was recently published by The Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS). PNAS is a peer reviewed journal of the National Academy of Sciences that broadly spans across the areas of biological, physical and social sciences.

V. cholerae choleraeis found naturally on various surfaces within marine environments. When water or food contaminated with V. cholerae is consumed by humans, it colonizes the gastrointestinal tract and causes cholera.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, cholera is an intestinal infection that causes diarrhea, vomiting, circulatory collapse and shock. If left untreated, 25 to 50% of severe cholera cases can be fatal. Cholera is a leading cause of epidemic diarrhea in parts of the world and the World Health Organization (WHO) estimates up to four million people are infected each year.

Lloyd was the primary author and completed the article as his thesis project under the advisement of Klose, who has been studying the pathogenic mechanisms of V. cholerae for 30 years. Lloyd worked in Klose’s laboratory for five years.

He learned how to study V. cholerae, genetically manipulate the bacteria, and measure its ability to spread disease, bind to red blood cells and form biofilms, which are surfaces where communities of bacteria form that are more resistant to antibiotics. Lloyd is currently interviewing for several postdoctoral fellowship positions in laboratories across the nation.

“By taking advantage of the structural similarities of functional domains in two large adhesins [cell-surface components or appendages of bacteria that facilitate adhesion to other cells, usually in the host they are infecting or living in] produced by two different organisms, we were able to characterize an effective inhibitor to intestinal colonization and biofilm formation,” said Lloyd.

In collaboration with the laboratories of Peter Davies, Canada research chair in Protein Engineering and professor of biomedical and molecular sciences at Queens University, Canada, and Ilja Voets, professor of chemical engineering and chemistry at Eindhoven University, Netherlands, Lloyd and Klose successfully identified a peptide, a short chain of amino acids that make up proteins, that can inhibit the virulence of V. cholerae.

They discovered that the peptide inhibiters that bind to Marinomonas primoryensis, an Antarctic bacterium that sticks to microalgae in a similar manner to how V. cholerae sticks to human intestines, can also disrupt V. cholerae from adhering to human cells, forming biofilms and colonizing the gastrointestinal tract.

“We demonstrated that these peptide inhibitors could inhibit both biofilm formation as well as intestinal colonization by V. cholerae,” said Klose. “It is possible that this could be part of intervention strategies to inhibit these bacteria from causing disease and persisting in the environment.”

The Klose Lab is a part of The South Texas Center for Emerging Infectious Diseases (STCEID) and specializes in studying how bacteria cause disease. The lab has worked most extensively with V. cholerae and Francisella tularensis, the bacterium that causes tularemia, or rabbit fever.

STCEID researchers specialize in the study of infectious diseases and form one of the premier centers for this type of research in the nation. The Center connects state-of-the art facilities with the diverse expertise of its faculty to cultivate an environment that answers critical questions relating to emerging and bioweapon-related diseases.

The facilities and faculty at the Center also serve an important role in providing hands-on training to undergraduate and graduate students who intend to pursue careers in science and technology.

“This project and others like it have equipped me with an in-depth knowledge of molecular biology, coding, and high throughput data analysis,” said Lloyd.

"Our graduate students that come to UTSA to get Master’s and Ph.D. degrees are in the best place to study infectious diseases," added Klose.

END

UTSA researchers discover new method to inhibit cholera infection

2023-11-07

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

The molecular basis of ventilator-induced diaphragm weakness

2023-11-07

A study presents evidence that mitochondrial fragmentation is a proximal mechanism underlying ventilator-induced diaphragm dysfunction (VIDD)—and identifies a possible therapeutic to limit diaphragm atrophy during a stay in intensive care. Previous research has established that many of the cellular pathways responsible for VIDD are kicked off by oxidative stress stemming from diaphragm inactivity. Stefan Matecki and colleagues studied the molecular causes of this oxidative stress in mice. Just six hours on mechanical ventilation was enough to increase expression of dynamin-related protein 1 (DRP1), which is involved in mitochondrial ...

Bisphenol A and asthma in mice

2023-11-07

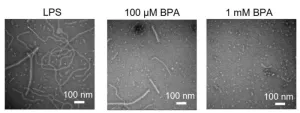

The “hygiene hypothesis” posits that allergic asthma can be triggered by a childhood environment that is too clean and sterile. One studied mechanism underlying this relationship is the influence of microbial lipopolysaccharides (LPS), which train the immune system. In the absence of LPS, Toll-like receptors in the human body will become more sensitive, which can lead to an exaggerated allergic response to triggers such as house dust mites. Mingliang Fang and colleagues explored how the environmental pollutant bisphenol ...

Mountain goats seek snow to shake off insects

2023-11-07

Losing summer snow patches may hit mountain goats hard, according to a study that suggests that goats seek out snow to avoid biting insects. Many cold-adapted species take advantage of patches of snow that linger through the summer, as corridors for travel, sources of drinking water, zones for cooling off, or places to play. As the climate changes, many species will have reduced access to snow patches. Forest Hayes and Joel Berger explored what this lack of summer snow might mean for mountain goats (Oreamnos americanus) in Glacier National Park, which has lost 85% of its glaciers since 1850. The team studied goats in the park—along with another population 1,000 ...

Mapping the landscape: Amsterdam UMC receives millions to lead European research into obesity

2023-11-07

Obesity is a growing health problem that disproportionately affects people and communities with a low socio-economic position in Europe. Thanks to a Horizon grant worth more than 10 million euros, Jeroen Lakerveld, epidemiologist at Amsterdam UMC, is now set to lead a European consortium in better identifying the causes of obesity and designing guidelines to tackle the problem.

"Social and cultural factors play a role in our lifestyle behaviours but so do our genes and the environment in which we live and work. Residents of neighbourhoods are not equally exposed to unhealthy factors: ...

Guilt not as persuasive if directly tied to personal responsibility

2023-11-07

PULLMAN, Wash. – Invoking a sense of guilt—a common tool used by advertisers, fundraisers and overbearing parents everywhere—can backfire if it explicitly holds a person responsible for another’s suffering, a meta-analysis of studies revealed.

While guilt is widely used to try and persuade people to act, research has been mixed on its effectiveness in spurring behavior change. This analysis, published in the journal Frontiers in Psychology, found that overall guilt had only a small persuasive effect, which is in line with previous research.

However, researchers uncovered that guilt worked better ...

Previous genetic association studies involving people with European ancestry may be inaccurate

2023-11-07

Researchers have found that previous studies analyzing the genomes of people with European ancestry may have reported inaccurate results by not fully accounting for population structure. By considering mixed genetic lineages, researchers at the National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI), part of the National Institutes of Health, demonstrated that previously inferred links between a genomic variant that helps digest lactose and traits such as a person’s height and cholesterol level may not be valid.

The study, published in Nature Communications, shows that people with European ancestry, who were previously treated as a genetically homogenous group in large-scale genetic ...

Contraceptive pills might impair fear-regulating regions in women’s brains

2023-11-07

More than 150 million women worldwide use oral contraceptives. Combined OCs (COCs), made up of synthetic hormones, are the most common type. Sex hormones are known to modulate the brain network involved in fear processes.

Now a team of researchers in Canada has investigated current and lasting effects of COC use, as well as the role of body-produced and synthetic sex hormones on fear-related brain regions, the neural circuitry via which fear is processed in the brain.

“In our study, we show that healthy women currently using COCs had a thinner ventromedial prefrontal cortex than men,” said Alexandra Brouillard, ...

Risk of dying in hospital from respiratory causes is higher in the summer than in the winter

2023-11-07

Global warming caused by climate change could exacerbate the burden of inpatient mortality from respiratory diseases during the warm season. This is the main conclusion of a study led by the Barcelona Institute for Global Health (ISGlobal), a centre supported by the "la Caixa" Foundation, and published in The Lancet Regional Health - Europe. The results could help health facilities adapt to climate change.

The research team analysed the association between ambient temperature and in-hospital mortality from respiratory diseases in the provinces of Madrid and Barcelona between 2006 and 2019. ...

Poetry can help people cope with loneliness or isolation

2023-11-07

Reading, writing and sharing poetry can help people cope with loneliness or isolation and reduce feelings of anxiety and depression, a new study shows.

Research by the University of Plymouth and Nottingham Trent University, funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council, found that many people who took to sharing, discussing and writing poetry as a means to deal with the COVID-19 pandemic experienced “demonstrable positive impact on their wellbeing”.

The findings are based on a survey of 400 people which showed that poetry helped those experiencing common mental health symptoms as well as those suffering from grief.

It was carried out with registered users of the ...

French love letters confiscated by Britain finally read after 265 years

2023-11-07

UNDER STRICT EMBARGO UNTIL 19:01 (US ET) ON MONDAY 6TH NOVEMBER 2023 / 00:01AM (UK TIME) ON TUESDAY 7TH NOVEMBER 2023

Over 100 letters sent to French sailors by their fiancées, wives, parents and siblings – but never delivered – have been opened and studied for the first time since they were written in 1757-8.

The messages offer extremely rare and moving insights into the loves, lives and family quarrels of everyone from elderly peasants to wealthy officer’s wives.

The messages were seized by Britain’s Royal Navy during the Seven Years’ War, taken to the Admiralty in London ...