(Press-News.org) Glass stronger and tougher than steel? A new type of damage-tolerant metallic glass, demonstrating a strength and toughness beyond that of any known material, has been developed and tested by a collaboration of researchers with the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE)'s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab)and the California Institute of Technology. What's more, even better versions of this new glass may be on the way.

"These results mark the first use of a new strategy for metallic glass fabrication and we believe we can use it to make glass that will be even stronger and more tough," says Robert Ritchie, a materials scientist who led the Berkeley contribution to the research.

The new metallic glass is a microalloy featuring palladium, a metal with a high "bulk-to-shear" stiffness ratio that counteracts the intrinsic brittleness of glassy materials.

"Because of the high bulk-to-shear modulus ratio of palladium-containing material, the energy needed to form shear bands is much lower than the energy required to turn these shear bands into cracks," Ritchie says. "The result is that glass undergoes extensive plasticity in response to stress, allowing it to bend rather than crack."

Ritchie, who holds joint appointments with Berkeley Lab's Materials Sciences Division and the University of California (UC) Berkeley's Materials Science and Engineering Department, is one of the co-authors of a paper describing this research published in the journal Nature Materials under the title "A Damage-Tolerant Glass."

Co-authoring the Nature Materials paper were Marios Demetriou (who actually made the new glass), Maximilien Launey, Glenn Garrett, Joseph Schramm, Douglas Hofmann and William Johnson of Cal Tech, one of the pioneers in the field of metallic glass fabrication.

Glassy materials have a non-crystalline, amorphous structure that make them inherently strong but invariably brittle. Whereas the crystalline structure of metals can provide microstructural obstacles (inclusions, grain boundaries, etc.,) that inhibit cracks from propagating, there's nothing in the amorphous structure of a glass to stop crack propagation. The problem is especially acute in metallic glasses, where single shear bands can form and extend throughout the material leading to catastrophic failures at vanishingly small strains.

In earlier work, the Berkeley-Cal Tech collaboration fabricated a metallic glass, dubbed "DH3," in which the propagation of cracks was blocked by the introduction of a second, crystalline phase of the metal. This crystalline phase, which took the form of dendritic patterns permeating the amorphous structure of the glass, erected microstructural barriers to prevent an opened crack from spreading. In this new work, the collaboration has produced a pure glass material whose unique chemical composition acts to promote extensive plasticity through the formation of multiple shear bands before the bands turn into cracks.

"Our game now is to try and extend this approach of inducing extensive plasticity prior to fracture to other metallic glasses through changes in composition," Ritchie says. "The addition of the palladium provides our amorphous material with an unusual capacity for extensive plastic shielding ahead of an opening crack. This promotes a fracture toughness comparable to those of the toughest materials known. The rare combination of toughness and strength, or damage tolerance, extends beyond the benchmark ranges established by the toughest and strongest materials known."

The initial samples of the new metallic glass were microalloys of palladium with phosphorous, silicon and germanium that yielded glass rods approximately one millimeter in diameter. Adding silver to the mix enabled the Cal Tech researchers to expand the thickness of the glass rods to six millimeters. The size of the metallic glass is limited by the need to rapidly cool or "quench" the liquid metals for the final amorphous structure.

"The rule of thumb is that to make a metallic glass we need to have at least five elements so that when we quench the material, it doesn't know what crystal structure to form and defaults to amorphous," Ritchie says.

The new metallic glass was fabricated by co-author Demetriou at Cal Tech in the laboratory of co-author Johnson. Characterization and testing was done at Berkeley Lab by Ritchie's group.

"Traditionally strength and toughness have been mutually exclusive properties in materials, which makes these new metallic glasses so intellectually exciting," Ritchie says. "We're bucking the trend here and pushing the envelope of the damage tolerance that's accessible to a structural metal."

INFORMATION:

The characterization and testing research at Berkeley Lab was funded by DOE's Office of Science. The fabrication work at Cal Tech was funded by the National Science Foundation.

Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory is a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) national laboratory managed by the University of California for the DOE Office of Science. Berkeley Lab provides solutions to the world's most urgent scientific challenges including sustainable energy, climate change, human health, and a better understanding of matter and force in the universe. It is a world leader in improving our lives through team science, advanced computing, and innovative technology. Visit our at www.lbl.gov

New glass tops steel in strength and toughness

2011-01-11

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

How do you make lithium melt in the cold?

2011-01-11

Washington, D.C. — Sophisticated tools allow scientists to subject the basic elements of matter to conditions drastic enough to modify their behavior. By doing this, they can expand our understanding of matter. A research team including three Carnegie scientists was able to demonstrate surprising properties of the element lithium under intense pressure and low temperatures. Their results were published Jan. 9 on the Nature Physics website.

Lithium is the first metal in the periodic table and is the least dense solid element at room temperature. It is most commonly known ...

First strawberry genome sequence promises better berries

2011-01-11

DURHAM, N.H. – An international team of researchers, including several from the University of New Hampshire, have completed the first DNA sequence of any strawberry plant, giving breeders much-needed tools to create tastier, healthier strawberries. Tom Davis, professor of biological sciences at UNH, and postdoctoral researcher Bo Liu were significant contributors to the genome sequence of the woodland strawberry, which was published last month in the journal Nature Genetics.

"We now have a resource for everybody who's interested in strawberry genetics. We can answer questions ...

New insights into sun's photosphere reported by NJIT researcher at Big Bear

2011-01-11

NJIT Distinguished Professor Philip R. Goode and the research team at Big Bear Solar Observatory (BBSO) have reported new insights into the small-scale dynamics of the Sun's photosphere. The observations were made during a period of historic inactivity on the Sun and reported in The Astrophysical Journal . http://iopscience.iop.org/2041-8205/714/1/L31 The high-resolution capabilities of BBSO's new 1.6-meter aperture solar telescope have made such work possible.

"The smallest scale photospheric magnetic field seems to come in isolated points in the dark intergranular ...

Body dysmorphic disorder patients who loathe appearance often get better, but it could take years

2011-01-11

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — In the longest-term study so far to track people with body dysmorphic disorder, a severe mental illness in which sufferers obsess over nonexistent or slight defects in their physical appearance, researchers at Brown University and Rhode Island Hospital found high rates of recovery, although recovery can take more than five years.

The results, based on following 15 sufferers of the disease over an eight-year span, appear in the current issue of the Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease.

"Compared to what we expected based on a prior ...

Debunking solar energy efficiency measurements

2011-01-11

In recent years, developers have been investigating light-harvesting thin film solar panels made from nanotechnology –– and promoting efficiency metrics to make the technology marketable. Now a Tel Aviv University researcher is providing new evidence to challenge recent "charge" measurements for increasing solar panel efficiency.

Offering a less expensive, smaller solution than traditional panels, Prof. Eran Rabani of Tel Aviv University's School of Chemistry at the Raymond and Beverly Sackler Faculty of Exact Sciences puts a lid on some current hype that promises to ...

Study identifies new genetic signatures of breast cancer drug resistance

2011-01-11

A new study conducted by Josh LaBaer's research team in the Biodesign Institute at Arizona State University has pinpointed more than 30 breast cancer gene targets ---including several novel genes---that are involved in drug resistance to a leading chemotherapy treatment.

The results of the study may one day aid in the treatment of the one in ten U.S. women who will develop breast cancer, by empowering physicians with a more personalized approach to therapy as well as a new tool for the early screening of those that may ultimately become resistant to chemotherapy.

Drugs ...

Study estimates land available for biofuel crops

2011-01-11

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. — Using detailed land analysis, Illinois researchers have found that biofuel crops cultivated on available land could produce up to half of the world's current fuel consumption – without affecting food crops or pastureland.

Published in the journal Environmental Science and Technology, the study led by civil and environmental engineering professor Ximing Cai identified land around the globe available to produce grass crops for biofuels, with minimal impact on agriculture or the environment.

Many studies on biofuel crop viability focus on biomass yield, ...

Miscanthus has a fighting chance against weeds

2011-01-11

University of Illinois research reports that several herbicides used on corn also have good selectivity to Miscanthus x giganteus (Giant Miscanthus), a potential bioenergy feedstock.

"No herbicides are currently labeled for use in Giant Miscanthus grown for biomass," said Eric Anderson, an instructor of bioenergy for the Center of Advanced BioEnergy Research at the University of Illinois. "Our research shows that several herbicides used on corn are also safe on this rhizomatous grass."

M. x giganteus is sterile and predominantly grown by vegetative propagation, or planting ...

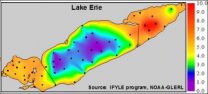

Lake Erie hypoxic zone doesn't affect all fish the same, study finds

2011-01-11

WEST LAFAYETTE, Ind. - Large hypoxic zones low in oxygen long have been thought to have negative influences on aquatic life, but a Purdue University study shows that while these so-called dead zones have an adverse affect, not all species are impacted equally.

Tomas Höök, an assistant professor of forestry and natural resources, and former Purdue postdoctoral researcher Kristen Arend used output from a model to estimate how much dissolved oxygen was present in Lake Erie's hypoxic zone each day from 1987 to 2005. That information was compared with biological ...

Being poor can suppress children's genetic potentials

2011-01-11

AUSTIN, Texas — Growing up poor can suppress a child's genetic potential to excel cognitively even before the age of 2, according to research from psychologists at The University of Texas at Austin.

Half of the gains that wealthier children show on tests of mental ability between 10 months and 2 years of age can be attributed to their genes, the study finds. But children from poorer families, who already lag behind their peers by that age, show almost no improvements that are driven by their genetic makeup.

The study of 750 sets of twins by Assistant Professor Elliot ...