(Press-News.org) The United States House of Representatives held more than 700 votes in 2023, but fewer than 30 bills were signed into law. Partisan politics may explain why, with polarization potentially causing enough friction to slow down the legislative process and make the passage of fewer, farther-reaching public laws likelier, according to researchers.

The collaborators from Penn State and Colorado State University studied levels of polarization and patterns in the passage of budget bills and public laws from 1948 through 2020. They found that as polarization increased, especially in the mid-1990s and 2000s, Congress passed fewer bills, but the bills they did pass were larger and led to more dramatic changes in public policy. They reported their findings in the Policy Studies Journal.

“Punctuated equilibrium theory is the idea that in the American policy process you tend to see periods of stasis or incremental changes occurring over time, and then occasionally bigger punctuations happen, like the passage of the Affordable Care Act or a big infrastructure bill,” said study co-author Daniel Mallinson, associate professor of public policy and administration at Penn State Harrisburg. “We found that as polarization has increased in the U.S., these dynamics of stasis and punctuation have gotten exaggerated. This happens because polarization introduces greater friction in policymaking, so it’s harder to change the status quo, but when you do, the change is bigger.”

The researchers focused on budget bills because of the ease of calculating percentage changes in line items from year to year, allowing them to capture incremental versus big changes. For the public laws analysis, they focused on the number of bills passed each year excluding symbolic laws, such as the renaming of a post office. The researchers used a five-year moving average approach — where the first five-year window covers years 1948-52, the second five-year window covers years 1949-53, and so on — to calculate kurtosis, or the distribution of these periods of stasis and punctuation in policymaking over time.

They used measurements of the difference of mean party ideology in the U.S. House of Representatives to track polarization over time. Then they plotted budget kurtosis, public law kurtosis and polarization over time and conducted additional analyses to see if factors like divided government could account for exaggerated patterns in the data.

“Our findings indicate that, while ‘gridlock’ is not accurately descriptive of Congressional behavior, we are seeing an increasingly unstable policy process, characterized by long periods of inaction punctuated by moments of enormous volatility,” said Clare Brock, first author of the study and assistant professor of American politics and public policy at Colorado State University. “This is not a new pattern, but it is becoming more exaggerated.”

The researchers found a correlation between polarization and periods of stasis and punctuation in policymaking. As polarization jumped in the 1990s and during President Barack Obama’s administration, the periods of stasis grew longer and Congress passed fewer bills, but the bills that did pass included large-scale changes in budgets.

“The scholarly and public narratives for a while now have been that Congress doesn’t do anything,” Mallinson said. “This work shows that maybe numerically Congress is doing less, not passing as much legislation or perhaps there is more stasis because of the effects of polarization, but Congress is still doing work that is important to the American public and impacts Americans’ lives.”

Understanding that government still works even during periods of stasis in policymaking is important for maintaining a healthy democracy, according to Mallinson. He and Brock are currently working on a book that examines polarization and its effects on policymaking in more detail.

“It’s a concerning belief when you think the government isn’t doing anything for you,” Mallinson said. “We see that belief manifest in populism and populist support for divisive candidates who take advantage of and perpetuate that problematic belief.”

END

Political polarization may slow legislation, make higher-stakes laws likelier

2024-01-26

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Common cold or COVID-19? Some T cells are ready to combat both

2024-01-26

Scientists at La Jolla Institute for Immunology (LJI) have found direct evidence that exposure to common cold coronaviruses can train T cells to fight SARS-CoV-2. In fact, prior exposure to a common cold coronavirus appears to partially protect mice from lung damage during a subsequent SARS-CoV-2 infection.

The new research, published recently in Nature Communications, provides an important first look at how "cross-reactive" T cells—which can fight multiple viruses from the same family—develop in an animal model. "We are learning how these immune cells develop ...

The science behind mindfulness: How one University of Ottawa professor embraced it for the benefit of her students

2024-01-26

Understanding the neuroscience and physiological basis of the brain and training its networks to combat anxiety and life’s stressors

Professor Andra Smith, from the School of Psychology at the Faculty of Social Sciences, has combined her research and her personal experience with mindfulness to teach the course Neuroscience of Mindfulness: Neurons to Wellness. Her interest in neuroscience explores how to optimize cognitive processes behind decision-making, organizing behaviour, setting goals while taking the necessary steps ...

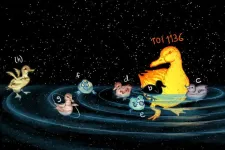

UC Irvine-led team unravels mysteries of planet formation and evolution in distant solar system

2024-01-26

A recently discovered solar system with six confirmed exoplanets and a possible seventh is boosting astronomers’ knowledge of planet formation and evolution. Relying on a globe-spanning arsenal of observatories and instruments, a team led by researchers at the University of California, Irvine has compiled the most precise measurements yet of the exoplanets’ masses, orbital properties and atmospheric characteristics.

In a paper published today in The Astronomical Journal, the researchers share ...

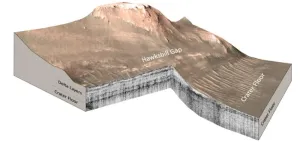

Confirmation of ancient lake on Mars builds excitement for Perseverance rover's samples

2024-01-26

If life ever existed on Mars, the Perseverance rover’s verification of lake sediments at the base of the Jezero crater reinforces the hope that traces might be found in the crater.

In new research published in the journal Science Advances, a team led by UCLA and The University of Oslo shows that at some point, the crater filled with water, depositing layers of sediments on the crater floor. The lake subsequently shrank and sediments carried by the river that fed it formed an enormous delta. As the lake dissipated over time, the sediments in the crater were eroded, forming ...

USC Stem Cell study shows how gene activity modulates the amount of immune cell production in mice

2024-01-26

As people age or become ill, their immune systems can become exhausted and less capable of fighting off viruses such as the flu or COVID-19. In a new mouse study funded in part by the National Institutes of Health and published in Science Advances, researchers from the USC Stem Cell lab of Rong Lu describe how specific gene activity could potentially enhance immune cell production.

“Hematopoietic stem cells, or HSCs, produce blood and immune cells, but not all HSCs are equally productive,” said the study’s corresponding author Rong Lu, PhD, ...

How waves and mixing drive coastal upwelling systems

2024-01-26

They are among the most productive and biodiverse areas of the world's oceans: coastal upwelling regions along the eastern boundaries of the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. There, equatorward winds cause near-surface water to move away from the coast. This brings cold, nutrient-rich water from the depths to the surface, inducing the growth of phytoplankton and providing the basis for a rich marine ecosystem in these regions.

In some tropical regions, however, productivity is high even when the upwelling favourable winds are ...

How a timekeeping gene affects tumor growth depends entirely on context

2024-01-26

JANUARY 23, 2024, NEW YORK – A Ludwig Cancer Research study has found that the circadian clock—which synchronizes physiological and cellular activities with the day-night cycle and is generally thought to be tumor suppressive—in fact has a contextually variable role in cancer.

“A lot of evidence suggests that the biological clock is broken in cancer cells, so we expected its disruption would fuel tumor growth in mouse models of melanoma,” said Chi Van Dang, scientific director of the Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research, who led the study with Research Associate Xue Zhang. “But, contrary to our expectations, ...

UT Extension Consumer Economics Specialist named National Educator of the Year for 2023

2024-01-26

An assistant professor and consumer economics specialist with University of Tennessee Extension has been recognized by the Association for Financial Counseling and Planning Education (AFCPE) as the organization’s Educator of the Year for 2023. Christopher Sneed was among ten individuals, organizations, special projects and initiatives expanding access to personal finance resources and education across the country recognized as part of the 2023 AFCPE Awards late last year.

The AFCPE’s Mary Ellen Edmondson Educator of the Year Award honors ...

Female reproductive milestones may be risk factors for diabetes and high cholesterol later in life

2024-01-26

Boston, MA – A new review of available evidence led by researchers at the Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institute suggests that female reproductive characteristics may be overlooked as risk factors that contribute to later metabolic dysfunction.

The review, “Reproductive risk factors across the female lifecourse and later metabolic health,” was published in the January 26 edition of Cell Metabolism.

Metabolic health is characterized by optimal blood glucose, lipids, blood pressure, and body fat. Alterations in these characteristics may lead to the development of type 2 diabetes or cardiovascular disease.

“Our ...

Using fMRI, new vision study finds promising model for restoring cone function

2024-01-26

In the retinas of human eyes, the cones are photoreceptor cells responsible for color vision, daylight vision, and the perception of small details. As vision scientists from the Division of Experimental Retinal Therapies at the University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine, Gustavo D. Aguirre and William A. Beltran have been working for decades to identify the basis of inherited retinal diseases. They previously showed they could recover missing cone function by reintroducing a copy of the normal gene in photoreceptor cells.

Both ...