(Press-News.org) There are many lingering mysteries from the COVID-19 pandemic. For instance, why does SARS-CoV-2, the virus behind the disease, cause severe symptoms in some patients, while many other coronaviruses don’t? And what causes strange symptoms to persist even after the infection has been cleared from a person’s system?

The world may now have the beginning of answers. In a study published today in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, a UCLA-led multidisciplinary research team explores one way that COVID-19 turns the immune system — which is crucial for keeping people alive — against the body itself, with potentially deadly results.

Using an artificial intelligence system they developed, the study authors scanned the entire collection of proteins produced by SARS-CoV-2 and then performed an exhaustive series of validation experiments. The scientists found that certain viral protein fragments, generated after the SARS-CoV-2 virus is broken down into pieces, can mimic a key component of the body’s machinery for amplifying immune signals. Their discoveries suggest that some of the most serious COVID-19 outcomes can result from these fragments overstimulating the immune system, thereby causing rampant inflammation in widely different contexts such as cytokine storms and lethal blood coagulation.

The study was led by corresponding author Gerard Wong, a professor of bioengineering at the UCLA Samueli School of Engineering and in the UCLA College’s chemistry and biochemistry department and microbiology, immunology and molecular genetics department.

“What we found deviates from the standard picture of viral infection,” said Wong, who is also a member of the California NanoSystems Institute at UCLA. “The textbooks tell us that after the virus is destroyed, the sick host ‘wins,’ and different pieces of virus can be used to train the immune system for future recognition. COVID-19 reminds us that it’s not this simple.

“For comparison, if one were to assume that after food gets digested into its molecular components, then its effects on the body are over, it would be very liberating; I wouldn’t have to worry about the half-dozen jelly donuts I just ate. However, this simple picture is not correct.”

The research team found SARS-CoV-2 fragments can imitate innate immune peptides, a class of immune molecules that amplify signals to activate the body’s natural defenses. Peptides are chains of amino acids like proteins, only shorter. These immune peptides can spontaneously assemble into new structures with double-stranded RNA, a special form of a molecule essential for building proteins from DNA, typically found in viral infections or released by dying cells.

The resultant hybrid complex of the immune peptides and double-stranded RNA kicks off a chain reaction that triggers an immune response.

In addition to their AI analysis, the researchers used state-of-the-art methods for elucidating nanoscale biological structures and conducted cell- and animal-based experiments. Compared to relatively harmless coronaviruses that cause the common cold, the team found that SARS-CoV-2 harbors many more combinations of fragments that can better mimic human immune peptides. Consistent with that, additional experiments with multiple cell types all consistently show that fragments of the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus prompt an amplified inflammatory response compared to those from a common cold coronavirus. Likewise, experiments with mice show that fragments from SARS-CoV-2 lead to huge immune response, especially in the lungs.

The findings could influence treatment for COVID-19 and efforts to identify and surveil future coronaviruses capable of causing pandemics.

“We may be able to look at the protein composition of this year’s coronavirus strains and figure out whether they’re potentially pandemic-capable or just going to cause the common cold,” Wong said.

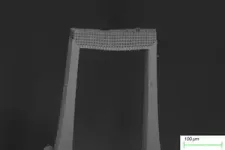

Wong and his colleagues concentrated on three SARS-CoV-2 fragments. Using a technique for analyzing detailed molecular structures called synchrotron X-ray diffraction, they found that, like the innate immune peptide, the SARS-CoV-2 fragments can organize double-stranded RNA into structures that stimulate the immune system.

“We saw that the various forms of debris from the destroyed virus can reassemble into these biologically active ‘zombie’ complexes,” Wong said. “It is interesting that the human peptide being imitated by the viral fragments has been implicated in rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis and lupus, and that different aspects of COVID-19 are reminiscent of these autoimmune conditions.”

The scientists also measured the entire set of genes expressed at the cellular level. By performing a comparison with internationally curated databases, the team found that the gene expression profile from cells exposed to SARS-CoV-2 “zombie” complexes closely resembled that from COVID-19 itself.

“What’s astonishing about the gene expression result is there was no active infection used in our experiments,” Wong said. “We did not even use the whole virus — rather only about 0.2% or 0.3% of it — but we found this incredible level of agreement that is highly suggestive.”

The findings may account for some peculiarities of COVID-19 infection.

For instance, that fragments from SARS-CoV-2 lead to excessive inflammation could help explain why some seemingly healthy people experience severe COVID-19. Normally, the activity of enzymes varies a great deal between healthy individuals — with levels differing by as much as a factor of 10. It is ultimately enzymes that are responsible for cutting virus particles into smaller and smaller pieces.

Evidence that persistence of SARS-CoV-2 fragments may drive illness also reinforces emerging clues about which treatments may show promise.

“Our results suggest we may be able to manage COVID-19 by inhibiting certain enzymes or enhancing others,” Wong said. “One could even imagine a strategy also based on mimicry, by using biologically inactive decoys that look enough like these viral fragments to compete for double-stranded RNA, but form complexes that don’t activate the immune system.”

Remnant viral fragments are known to exist in other viral infections, but their biological activities have not been systematically studied.

The collaborative effort for this study brought together a team with 24 departmental and institutional affiliations during a particularly challenging time of the pandemic. The first author is Yue Zhang, a former UCLA postdoctoral researcher and current assistant professor at Westlake University in Hangzhou, China. Additional UCLA-based co-authors are doctoral students Jaime de Anda, Jonathan Chen and Elizabeth Luo; HongKyu Lee of Harbor-UCLA Medical Center; Liana Chan, assistant adjunct professor of medicine at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA; Michael Yeaman, professor of medicine at the Geffen School of Medicine and director of the Institute for Infection and Immunity at the Lundquist Institute at Harbor-UCLA Medical Center; and Melody Li, assistant professor of microbiology, immunology and molecular genetics.

The study’s senior authors include Rich Gallo and Victor Nizet of UC San Diego and Silvio Antoniak and Nigel Mackman of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Co-authors are also affiliated with Harvard Medical School, the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource and the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory.

The study was supported by the National Science Foundation, the National Institutes of Health, the Department of Energy and institutional funding sources that include the UCLA W. M. Keck Foundation COVID-19 Research Award Program.

END

Viral protein fragments may unlock mystery behind serious COVID-19 outcomes

‘Zombie’ virus fragments continue to cause inflammation after the virus is destroyed

2024-01-29

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Endangered seabird shows surprising individual flexibility to adapt to climate change

2024-01-29

New research finds that individual behavioural flexibility and not evolutionary selection is driving the northward shift of Balearic shearwaters.

The findings were revealed through a decade-long study which tagged individual birds.

The results indicate that individual animals may have greater behavioural flexibility to respond to climate change impacts than previously thought.

How individual animals respond to climate change is key to whether populations will persist or go extinct. Many species are shifting their ranges as the environment warms, but up to now the mechanisms underlying ...

Spacing characteristics between vegetation could be a warning sign of degrading dryland ecosystems - study

2024-01-29

Scientists have found that the spatial arrangement of plants in drylands can be a sign of the environment degrading, according to a new study.

One of the iconic features of drylands is the striking appearance of islands of plants surrounded by bare soil. This spatial structure of arid vegetation has long fascinated scientists, but now a new study published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, has shed new light on why these plants group in this way.

An international team of scientists, including from the University of Birmingham, combined field data from 115 sites around the world, and used mathematical models and remote sensing to build a picture of how the ...

Researchers spying for signs of life among exoplanet atmospheres

2024-01-29

COLUMBUS, Ohio – The next generation of advanced telescopes could sharpen the hunt for potential extraterrestrial life by closely scrutinizing the atmospheres of nearby exoplanets, new research suggests.

The next generation of advanced telescopes could sharpen the hunt for potential extraterrestrial life by closely scrutinizing the atmospheres of nearby exoplanets, new research suggests.

Published recently in The Astronomical Journal, a new paper details how a team of astronomers from The Ohio State University examined upcoming telescopes’ ability to detect chemical ...

People are inclined to hide a contagious illness while around others, research shows

2024-01-29

A startling number of people conceal an infectious illness to avoid missing work, travel, or social events, new research at the University of Michigan suggests.

The findings are reported in Psychological Science, a journal of the Association for Psychological Science. Across a series of studies involving healthy and sick adults, 75% of the 4,110 participants said they had either hidden an infectious illness from others at least once or might do so in the future. Many participants reported boarding planes, going on dates, and engaging in other social interactions while secretly sick. More than 61% of healthcare workers participating in the study also ...

Racial and ethnic differences in hypertension-related telehealth

2024-01-29

A new study in the peer-reviewed journal Telemedicine and e-Health found that hypertension management via telehealth increased among Medicaid recipients regardless of race and ethnicity during the COVID-19 pandemic. Click here to read the article now.

Jun Soo Lee, PhD, from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and coauthors, reported that from February-April 2023, the number of hypertension-related telehealth outpatient visits per 100 persons increased from 0.01 to 6.13, and the number of hypertension-related in-person visits decreased from 61.88 to 52.63.

The investigators ...

Henry Ford Health helps advance precision medicine research in Michigan

2024-01-29

Michiganders will continue to have the opportunity to advance medical research aimed at advancing individualized health care through a renewed award to Henry Ford Health + Michigan State University Health Sciences from the National Institutes of Health’s (NIH) All of Us Research Program. The award includes $18.3 million in initial funding to support a consortium of 8 health care provider organizations with a presence in 16 states.

Henry Ford has led the consortium since 2017. The renewed award allows participation to continue until at least 2028. The multimillion-dollar multi-year award represents the largest NIH research grant in Henry Ford’s 108-year history.

All ...

Jobs and geography may affect hearing: New study maps hearing loss by state and county across the US

2024-01-29

Chicago, IL – January 24, 2024 – The first study to map the prevalence of bilateral hearing loss in the United States by state and county finds that rates of hearing loss are higher among men, non-Hispanic Whites, and residents of rural areas. Bilateral hearing loss is hearing loss in both ears.

West Virginia, Alaska, Wyoming, Oklahoma, and Arizona had the highest rates of hearing loss, while the District of Columbia, New Jersey, New York, Maryland, and Connecticut had the lowest (see top ten highest and ...

UChicago engineer driving key role in Great Lakes water transformation

2024-01-29

The Chicago-based Great Lakes ReNEW coalition has been awarded one of the largest, if not the largest, climate awards in the city’s history – up to $160 million over 10 years as one of the inaugural U.S. National Science Foundation’s Regional Innovation Engines.

Authorized in the “CHIPS and Science Act of 2022,” the NSF Engines program is designed to support the development of diverse regional coalitions of universities, local governments, the private sector and nonprofits to create solutions to today’s pressing issues.

Selected from an initial pool of more ...

Hydroxyurea significantly reduces infections in children with sickle cell anemia

2024-01-29

INDIANAPOLIS -- Clinical research led by Indiana University School of Medicine investigators and their collaborators in Uganda has revealed that hydroxyurea significantly reduces infections in children with sickle cell anemia. Their latest findings enhance strong evidence of hydroxyurea’s effectiveness and could ultimately reduce death in children in Africa, the continent most burdened by the disease.

The group’s research, recently published in the journal Blood, revealed that hydroxyurea treatment resulted in a remarkable ...

University of Manchester and SPIE announce $1 million endowment for postgraduate scholarships

2024-01-29

The University of Manchester and SPIE, the international society for optics and photonics have announced the establishment of the SPIE-Manchester Postgraduate Scholarship in Photonics.

The $500k gift from the SPIE Endowment Matching Program will be matched 100% by the University and will be used to support both early-career and returning researchers from the University’s Photon Science Institute in partnership with the Royce Institute, the UK’s national institute for advanced materials research and innovation.

The partnership was announced today (29 January) during the SPIE Photonics West conference in San Francisco.

Photonics is the study of light and its interactions ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Researchers achieve efficient bicarbonate-mediated integrated capture and electrolysis of carbon dioxide

Study reveals ancient needles and awls served many purposes

Key protein SYFO2 enables 'self-fertilization’ of leguminous plants

AI tool streamlines drug synthesis

Turning orchard waste into climate solutions: A simple method boosts biochar carbon storage

New ACP papers say health care must be more accessible and inclusive for patients and physicians with disabilities

Moisture powered materials could make cleaning CO₂ from air more efficient

Scientists identify the gatekeeper of retinal progenitor cell identity

American Indian and Alaska native peoples experience higher rates of fatal police violence in and around reservations

Research alert: Long-read genome sequencing uncovers new autism gene variants

Genetic mapping of Baltic Sea herring important for sustainable fishing

In the ocean’s marine ‘snow,’ a scientist seeks clues to future climate

Understanding how “marine snow” acts as a carbon sink

In search of the room temperature superconductor: international team formulates research agenda

Index provides flu risk for each state

Altered brain networks in newborns with congenital heart disease

Can people distinguish between AI-generated and human speech?

New robotic microfluidic platform brings ai to lipid nanoparticle design

COSMOS trial results show daily multivitamin use may slow biological aging

Immune cells play key role in regulating eye pressure linked to glaucoma

National policy to remedy harms of race-based kidney function estimation associated with increased transplants for Black patients

Study finds teens spend nearly one-third of the school day on smartphones, with frequent checking linked to poorer attention

Team simulates a living cell that grows and divides

Study illuminates the experiences of people needing to seek abortion care out of state

Digital media use and child health and development

Seeking abortion care across state lines after the Dobbs decision

Smartphone use during school hours and association with cognitive control in youths ages 11 to 18

Maternal acetaminophen use and child neurodevelopment

Digital microsteps as scalable adjuncts for adults using GLP-1 receptor agonists

Researchers develop a biomimetic platform to enhance CAR T cell therapy against leukemia

[Press-News.org] Viral protein fragments may unlock mystery behind serious COVID-19 outcomes‘Zombie’ virus fragments continue to cause inflammation after the virus is destroyed