(Press-News.org)

A new research study examined the results from data generated by citizen scientists using a simple web-based motor test. The big data approach provides researchers with a unique way to explore how people correct for motor control errors. The resulting insights may one day pave the way for personalized physical therapy or tailor an athlete’s training routine. The results are available in the January 30th issue of the journal Nature Human Behaviour.

“This exploratory approach does not replace lab based studies, but complements them, asking whether motor behavior can generalize to the greater population,” said Jonathan Tsay, assistant professor in the Department of Psychology at Carnegie Mellon University and first author on the paper. “I see this large-scale approach as a way to democratize motor learning research.”

Traditionally, motor learning scientists have studied how people learn motor skills in a lab setting using expensive equipment to capture the subtle changes in a person’s movement in response to movement errors. These studies often involve a small number of participants. Whether these results generalize to the larger population remains unknown.

Tsay wanted to explore motor skills from a new perspective, using big data. To gather the data, he developed a simple motor-learning assessment that people could take online in the comfort of their homes. The result is a dataset of more than 2,000 sessions from a diverse participant population.

The study can also evaluate different underlying processes in motor learning, that is, the relative contribution of subconscious, implicit motor learning, and conscious, explicit motor learning. With the data in hand, Tsay was able to examine how demographic variables affect the relative contribution of these two learning styles.

The short, at-home test took about eight minutes compared to a normal 80-minute experiment in the lab. Many participants logged back in and contributed multiple sessions to the database, allowing the research team to track changes in motor learning efficiently.

The potential of the big data lies in a better understanding of variables, like gender, age, visual impairment and even video game experience, that can impact motor adaptation.

Tsay points to age as an example. It may seem obvious that age would be an important factor affecting motor adaptation, but the effect of age has been mixed in laboratory studies. The confusion may be in part due to the small sample size and the focus on extreme age groups (very young and very old).

Using big data, Tsay and his colleagues were able to examine age as a continuous variable. The results showed how participants modified their strategies to correct for a motor error across the lifespan, with adaptation peaking between 35 and 45 years of age. These adaptations have been missed by previous studies involving only a limited sample size.

“Using machine learning and other techniques, [this approach allowed us] to predict who would be successful at motor learning and what properties — speed of movement and reaction time — are good predictors of success in motor learning during a session,” said Tsay. “The results we found in this exploratory big data manner can be brought back to the lab to do more hypothesis-driven [studies] to find the mechanism behind the finding we see online.”

The simple motor learning task was only able to predict about 15% of the variance in the study, which limits the insights that can be drawn from these results. In addition, the motor task was not conducted under an experimenter’s supervision or specifically controlling for parameters, like type of technology and internet speed, that increased noise in the data. Despite these limitations, Tsay still believes this large-scale approach is able to examine this variability in a detailed manner, drawing insights that can be valuable to the motor research community.

“Many, many questions in psychology are amenable to on-line testing, but there are few motor studies,” said Richard Ivry, distinguished professor in psychology at the University of California, Berkeley and co-author on the study. “The NatHumBehav study further adds to our confidence that on-line studies can be very meaningful for studying motor control, and I know that many labs around the world have taken advantage of these tools.”

Tsay and Ivry were joined by Hrach Asmerian and Ken Nakayama at University of California, Berkeley, Laura Germine at Harvard Medical School and Jeremy Wilmer at Wellesley College on the study, titled “Large-scale citizen science reveals predictors of sensorimotor adaptation.” The study received funding from the National Institute of Health National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke.

END

New research into the marine phosphorus cycle is deepening our understanding of the impact of human activities on ecosystems in coastal seas.

The research, co-led by the University of East Anglia, in partnership with the Sino-UK Joint Research Centre at the Ocean University of China, looked at the impact of aerosols and river run-off on microalgae in the coastal waters of China.

It identified an ‘Anthropogenic Nitrogen Pump’ which changes the phosphorus cycle and therefore likely coastal biodiversity and associated ecosystem services.

In a balanced ecosystem, microalgae, also known as phytoplankton, provide food for a wide ...

Life has a challenging tempo. Sometimes, it moves faster or slower than we’d like. Nevertheless, we adapt. We pick up the rhythm of conversations. We keep pace with the crowd walking a city sidewalk.

“There are many instances where we have to do the same action but at different tempos. So the question is, how does the brain do it," says Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Assistant Professor Arkarup Banerjee.

Now, Banerjee and collaborators have uncovered a new clue that suggests the brain bends our processing of time to suit our ...

People of religious faith may have experienced lower levels of unhappiness and stress than secular people during the UK’s Covid-19 lockdowns in 2020 and 2021, according to new University of Cambridge research.

The findings follow a recently published Cambridge-led study suggesting that worsening mental health after experiencing Covid infection – either personally or in those close to you – was also somewhat ameliorated by religious belief. This study looked at the US population during early 2021.

University of Cambridge economists argue ...

Stockholm, January 30, 2024 — Members of the AD-RIDDLE consortium announced today that they will begin a new initiative that aims to bridge the gap between Alzheimer’s research, implementation science, and precision medicine. The AD-RIDDLE programme will offer healthcare professionals a suite of validated solutions for timely detection and diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease and dementias, to match individuals with the right interventions at the right time, enabling people to better understand what they can do to reduce risk and prevent cognitive decline.

Alzheimer’s disease represents a major public ...

HONG KONG (18 Jan 2024) — Goats can tell the difference between a happy-sounding human voice and an angry-sounding one, according to research co-led by Professor Alan McElligott, an expert in animal behaviour and welfare at City University of Hong Kong (CityUHK).

The study reveals that goats may have developed a sensitivity to our vocal cues over their long association with humans, according to the study published in Animal Behaviour.

Long known for their own sonorous vocal skills, goats in the study tended to spend longer gazing towards the source of the sound after a change in the valence of a human voice, i.e., when the playback switched from a happier to ...

Cambridge scientists may have discovered a new way in which fasting helps reduce inflammation – a potentially damaging side-effect of the body’s immune system that underlies a number of chronic diseases.

In research published in Cell Reports, the team describes how fasting raises levels of a chemical in the blood known as arachidonic acid, which inhibits inflammation. The researchers say it may also help explain some of the beneficial effects of drugs such as aspirin.

Scientists have known for some time that our diet – particular a high calorie Western diet – can increase our risk of diseases ...

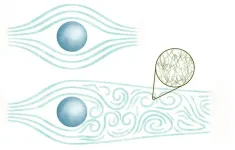

Every fluid — from Earth’s atmosphere to blood pumping through the human body — has viscosity, a quantifiable characteristic describing how the fluid will deform when it encounters some other matter. If the viscosity is higher, the fluid flows calmly, a state known as laminar. If the viscosity decreases, the fluid undergoes the transition from laminar to turbulent flow. The degree of laminar or turbulent flow is referred to as the Reynolds number, which is inversely proportional to the viscosity. The Reynolds law of dynamic similarity or Reynolds similitude, states that if two fluids flow around similar structures with different length ...

There is substantial geographic variation across the U.S. health care system to diagnose and treat early-stage Alzheimer’s disease with disease-modifying therapies, and engaging primary care providers in the effort may be a key to accelerating delivery of emerging new treatments, according to a new RAND report.

Enabling primary care practitioners to diagnose and evaluate patients for treatment eligibility would make the biggest impact on reducing wait times for specialists and increase the number of people treated with disease-modifying therapies from 2025 through 2044.

While primary care providers are technically capable of performing cognitive assessments, ...

A new causal link has been found between the presence of oncofoetal ecosystems and recurrence and response to immunotherapy in primary liver cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)

The findings will pave the way to use the presence of oncofoetal ecosystems as a biomarker to treat HCC, a disease with a poor prognosis that is typically diagnosed late

Singapore, 30 January 2024 - A team of clinician-scientists and researchers from the National Cancer Centre Singapore (NCCS), Agency for Science, Technology and Research (A*STAR), the Harry Perkins Institute of Medical Research and global research partners, has found a causal link between the presence of oncofoetal ...

Hf-based carbides are highly desirable candidates for thermal protection applications above 2000 ℃ due to their extremely high melting point and favorable mechanical properties. However, as a crucial indicator for composition design and performance assessment, the static oxidation behavior of Hf-based carbides at their potential service temperatures has been rarely studied.

In a study published in the KeAi journal Advanced Powder Materials, a group of researchers from Central South University and China Academy of Launch Vehicle Technology revealed the static oxidation mechanism ...