(Press-News.org) Using a virus-like delivery particle made from DNA, researchers from MIT and the Ragon Institute of MGH, MIT, and Harvard have created a vaccine that can induce a strong antibody response against SARS-CoV-2.

The vaccine, which has been tested in mice, consists of a DNA scaffold that carries many copies of a viral antigen. This type of vaccine, known as a particulate vaccine, mimics the structure of a virus. Most previous work on particulate vaccines has relied on protein scaffolds, but the proteins used in those vaccines tend to generate an unnecessary immune response that can distract the immune system from the target.

In the mouse study, the researchers found that the DNA scaffold does not induce an immune response, allowing the immune system to focus its antibody response on the target antigen.

“DNA, we found in this work, does not elicit antibodies that may distract away from the protein of interest,” says Mark Bathe, an MIT professor of biological engineering. “What you can imagine is that your B cells and immune system are being fully trained by that target antigen, and that’s what you want — for your immune system to be laser-focused on the antigen of interest.”

This approach, which strongly stimulates B cells (the cells that produce antibodies), could make it easier to develop vaccines against viruses that have been difficult to target, including HIV and influenza, as well as SARS-CoV-2, the researchers say. Unlike T cells, which are stimulated by other types of vaccines, these B cells can persist for decades, offering long-term protection.

“We’re interested in exploring whether we can teach the immune system to deliver higher levels of immunity against pathogens that resist conventional vaccine approaches, like flu, HIV, and SARS-CoV-2,” says Daniel Lingwood, an associate professor at Harvard Medical School and a principal investigator at the Ragon Institute. “This idea of decoupling the response against the target antigen from the platform itself is a potentially powerful immunological trick that one can now bring to bear to help those immunological targeting decisions move in a direction that is more focused.”

Bathe, Lingwood, and Aaron Schmidt, an associate professor at Harvard Medical School and principal investigator at the Ragon Institute, are the senior authors of the paper, which appears today in Nature Communications. The paper’s lead authors are Eike-Christian Wamhoff, a former MIT postdoc; Larance Ronsard, a Ragon Institute postdoc; Jared Feldman, a former Harvard University graduate student; Grant Knappe, an MIT graduate student; and Blake Hauser, a former Harvard graduate student.

Mimicking viruses

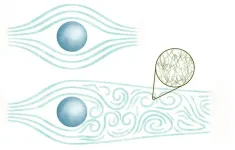

Particulate vaccines usually consist of a protein nanoparticle, similar in structure to a virus, that can carry many copies of a viral antigen. This high density of antigens can lead to a stronger immune response than traditional vaccines because the body sees it as similar to an actual virus. Particulate vaccines have been developed for a handful of pathogens, including hepatitis B and human papillomavirus, and a particulate vaccine for SARS-CoV-2 has been approved for use in South Korea.

These vaccines are especially good at activating B cells, which produce antibodies specific to the vaccine antigen.

“Particulate vaccines are of great interest for many in immunology because they give you robust humoral immunity, which is antibody-based immunity, which is differentiated from the T-cell-based immunity that the mRNA vaccines seem to elicit more strongly,” Bathe says.

A potential drawback to this kind of vaccine, however, is that the proteins used for the scaffold often stimulate the body to produce antibodies targeting the scaffold. This can distract the immune system and prevent it from launching as robust a response as one would like, Bathe says.

“To neutralize the SARS-CoV-2 virus, you want to have a vaccine that generates antibodies toward the receptor binding domain portion of the virus’ spike protein,” he says. “When you display that on a protein-based particle, what happens is your immune system recognizes not only that receptor binding domain protein, but all the other proteins that are irrelevant to the immune response you’re trying to elicit.”

Another potential drawback is that if the same person receives more than one vaccine carried by the same protein scaffold, for example, SARS-CoV-2 and then influenza, their immune system would likely respond right away to the protein scaffold, having already been primed to react to it. This could weaken the immune response to the antigen carried by the second vaccine.

“If you want to apply that protein-based particle to immunize against a different virus like influenza, then your immune system can be addicted to the underlying protein scaffold that it’s already seen and developed an immune response toward,” Bathe says. “That can hypothetically diminish the quality of your antibody response for the actual antigen of interest.”

As an alternative, Bathe’s lab has been developing scaffolds made using DNA origami, a method that offers precise control over the structure of synthetic DNA and allows researchers to attach a variety of molecules, such as viral antigens, at specific locations.

In a 2020 study, Bathe and Darrell Irvine, an MIT professor of biological engineering and of materials science and engineering, showed that a DNA scaffold carrying 30 copies of an HIV antigen could generate a strong antibody response in B cells grown in the lab. This type of structure is optimal for activating B cells because it closely mimics the structure of nano-sized viruses, which display many copies of viral proteins in their surfaces.

“This approach builds off of a fundamental principle in B-cell antigen recognition, which is that if you have an arrayed display of the antigen, that promotes B-cell responses and gives better quantity and quality of antibody output,” Lingwood says.

“Immunologically silent”

In the new study, the researchers swapped in an antigen consisting of the receptor binding protein of the spike protein from the original strain of SARS-CoV-2. When they gave the vaccine to mice, they found that the mice generated high levels of antibodies to the spike protein but did not generate any to the DNA scaffold.

In contrast, a vaccine based on a scaffold protein called ferritin, coated with SARS-CoV-2 antigens, generated many antibodies against ferritin as well as SARS-CoV-2.

“The DNA nanoparticle itself is immunogenically silent,” Lingwood says. “If you use a protein-based platform, you get equally high titer antibody responses to the platform and to the antigen of interest, and that can complicate repeated usage of that platform because you’ll develop high affinity immune memory against it.”

Reducing these off-target effects could also help scientists reach the goal of developing a vaccine that would induce broadly neutralizing antibodies to any variant of SARS-CoV-2, or even to all sarbecoviruses, the subgenus of virus that includes SARS-CoV-2 as well as the viruses that cause SARS and MERS.

To that end, the researchers are now exploring whether a DNA scaffold with many different viral antigens attached could induce broadly neutralizing antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 and related viruses.

###

The research was primarily funded by the National Institutes of Health, the National Science Foundation, and the Fast Grants program.

END

DNA particles that mimic viruses hold promise as vaccines

Using a DNA-based scaffold carrying viral proteins, researchers created a vaccine that provokes a strong antibody response against SARS-CoV-2

2024-01-30

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Citizen scientists contribute to motor learning research

2024-01-30

A new research study examined the results from data generated by citizen scientists using a simple web-based motor test. The big data approach provides researchers with a unique way to explore how people correct for motor control errors. The resulting insights may one day pave the way for personalized physical therapy or tailor an athlete’s training routine. The results are available in the January 30th issue of the journal Nature Human Behaviour.

“This exploratory approach does not replace lab based studies, but complements ...

New research shows how pollutants from aerosols and river run-off are changing the marine phosphorus cycle in coastal seas

2024-01-30

New research into the marine phosphorus cycle is deepening our understanding of the impact of human activities on ecosystems in coastal seas.

The research, co-led by the University of East Anglia, in partnership with the Sino-UK Joint Research Centre at the Ocean University of China, looked at the impact of aerosols and river run-off on microalgae in the coastal waters of China.

It identified an ‘Anthropogenic Nitrogen Pump’ which changes the phosphorus cycle and therefore likely coastal biodiversity and associated ecosystem services.

In a balanced ecosystem, microalgae, also known as phytoplankton, provide food for a wide ...

How a mouse’s brain bends time

2024-01-30

Life has a challenging tempo. Sometimes, it moves faster or slower than we’d like. Nevertheless, we adapt. We pick up the rhythm of conversations. We keep pace with the crowd walking a city sidewalk.

“There are many instances where we have to do the same action but at different tempos. So the question is, how does the brain do it," says Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Assistant Professor Arkarup Banerjee.

Now, Banerjee and collaborators have uncovered a new clue that suggests the brain bends our processing of time to suit our ...

Religious people coped better with the Covid-19 pandemic, research suggests

2024-01-30

People of religious faith may have experienced lower levels of unhappiness and stress than secular people during the UK’s Covid-19 lockdowns in 2020 and 2021, according to new University of Cambridge research.

The findings follow a recently published Cambridge-led study suggesting that worsening mental health after experiencing Covid infection – either personally or in those close to you – was also somewhat ameliorated by religious belief. This study looked at the US population during early 2021.

University of Cambridge economists argue ...

IHI launches a new interdisciplinary initiative to revolutionize the way Alzheimer’s disease is detected, diagnosed, prevented, and treated

2024-01-30

Stockholm, January 30, 2024 — Members of the AD-RIDDLE consortium announced today that they will begin a new initiative that aims to bridge the gap between Alzheimer’s research, implementation science, and precision medicine. The AD-RIDDLE programme will offer healthcare professionals a suite of validated solutions for timely detection and diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease and dementias, to match individuals with the right interventions at the right time, enabling people to better understand what they can do to reduce risk and prevent cognitive decline.

Alzheimer’s disease represents a major public ...

Goats can tell if you are happy or angry by your voice alone

2024-01-30

HONG KONG (18 Jan 2024) — Goats can tell the difference between a happy-sounding human voice and an angry-sounding one, according to research co-led by Professor Alan McElligott, an expert in animal behaviour and welfare at City University of Hong Kong (CityUHK).

The study reveals that goats may have developed a sensitivity to our vocal cues over their long association with humans, according to the study published in Animal Behaviour.

Long known for their own sonorous vocal skills, goats in the study tended to spend longer gazing towards the source of the sound after a change in the valence of a human voice, i.e., when the playback switched from a happier to ...

Scientists identify how fasting may protect against inflammation

2024-01-30

Cambridge scientists may have discovered a new way in which fasting helps reduce inflammation – a potentially damaging side-effect of the body’s immune system that underlies a number of chronic diseases.

In research published in Cell Reports, the team describes how fasting raises levels of a chemical in the blood known as arachidonic acid, which inhibits inflammation. The researchers say it may also help explain some of the beneficial effects of drugs such as aspirin.

Scientists have known for some time that our diet – particular a high calorie Western diet – can increase our risk of diseases ...

Superfluids could share characteristic with common fluids

2024-01-30

Every fluid — from Earth’s atmosphere to blood pumping through the human body — has viscosity, a quantifiable characteristic describing how the fluid will deform when it encounters some other matter. If the viscosity is higher, the fluid flows calmly, a state known as laminar. If the viscosity decreases, the fluid undergoes the transition from laminar to turbulent flow. The degree of laminar or turbulent flow is referred to as the Reynolds number, which is inversely proportional to the viscosity. The Reynolds law of dynamic similarity or Reynolds similitude, states that if two fluids flow around similar structures with different length ...

Alzheimer’s treatment roadblocks can be eased by engaging primary care providers in screenings

2024-01-30

There is substantial geographic variation across the U.S. health care system to diagnose and treat early-stage Alzheimer’s disease with disease-modifying therapies, and engaging primary care providers in the effort may be a key to accelerating delivery of emerging new treatments, according to a new RAND report.

Enabling primary care practitioners to diagnose and evaluate patients for treatment eligibility would make the biggest impact on reducing wait times for specialists and increase the number of people treated with disease-modifying therapies from 2025 through 2044.

While primary care providers are technically capable of performing cognitive assessments, ...

New study identifies link between presence of oncofoetal ecosystem and liver cancer recurrence

2024-01-30

A new causal link has been found between the presence of oncofoetal ecosystems and recurrence and response to immunotherapy in primary liver cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)

The findings will pave the way to use the presence of oncofoetal ecosystems as a biomarker to treat HCC, a disease with a poor prognosis that is typically diagnosed late

Singapore, 30 January 2024 - A team of clinician-scientists and researchers from the National Cancer Centre Singapore (NCCS), Agency for Science, Technology and Research (A*STAR), the Harry Perkins Institute of Medical Research and global research partners, has found a causal link between the presence of oncofoetal ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Novel camel antimicrobial peptides show promise against drug-resistant bacteria

Scientists discover why we know when to stop scratching an itch

A hidden reason inner ear cells die – and what it means for preventing hearing loss

Researchers discover how tuberculosis bacteria use a “stealth” mechanism to evade the immune system

New microscopy technique lets scientists see cells in unprecedented detail and color

Sometimes less is more: Scientists rethink how to pack medicine into tiny delivery capsules

Scientists build low-cost microscope to study living cells in zero gravity

The Biophysical Journal names Denis V. Titov the 2025 Paper of the Year-Early Career Investigator awardee

Scientists show how your body senses cold—and why menthol feels cool

Scientists deliver new molecule for getting DNA into cells

Study reveals insights about brain regions linked to OCD, informing potential treatments

Does ocean saltiness influence El Niño?

2026 Young Investigators: ONR celebrates new talent tackling warfighter challenges

Genetics help explain who gets the ‘telltale tingle’ from music, art and literature

Many Americans misunderstand medical aid in dying laws

Researchers publish landmark infectious disease study in ‘Science’

New NSF award supports innovative role-playing game approach to strengthening research security in academia

Kumar named to ACMA Emerging Leaders Program for 2026

AI language models could transform aquatic environmental risk assessment

New isotope tools reveal hidden pathways reshaping the global nitrogen cycle

Study reveals how antibiotic structure controls removal from water using biochar

Why chronic pain lasts longer in women: Immune cells offer clues

Toxic exposure creates epigenetic disease risk over 20 generations

More time spent on social media linked to steroid use intentions among boys and men

New study suggests a “kick it while it’s down” approach to cancer treatment could improve cure rates

Milken Institute, Ann Theodore Foundation launch new grant to support clinical trial for potential sarcoidosis treatment

New strategies boost effectiveness of CAR-NK therapy against cancer

Study: Adolescent cannabis use linked to doubling risk of psychotic and bipolar disorders

Invisible harms: drug-related deaths spike after hurricanes and tropical storms

Adolescent cannabis use and risk of psychotic, bipolar, depressive, and anxiety disorders

[Press-News.org] DNA particles that mimic viruses hold promise as vaccinesUsing a DNA-based scaffold carrying viral proteins, researchers created a vaccine that provokes a strong antibody response against SARS-CoV-2