(Press-News.org) New research published today in the journal Science has concluded that eradicating animals on the basis that they are not native in order to protect plant species, can be a flawed practice costing millions of dollars, and resulting in the slaughter of millions of healthy wild animals.

Introduced large herbivores, or megafauna, are claimed to have distinct and harmful ecological impacts, including damaging sensitive plants and habitats, reducing native plant diversity, and facilitating introduced plants. However, up to now these impacts have been studied without comparison to a proper control: native megafauna.

The new analysis, carried out by researchers at Aarhus University, Denmark, and the University of Oxford, UK, compared the effects of large mammal species listed as native and introduced, respectively, in 221 studies from across the world. They found that the two groups of animals had indistinguishable effects on both the abundance and diversity of native plants.

Study co-author Dr Jeppe Kristensen (The Environmental Change Institute, University of Oxford), said: ‘We do not find evidence to support the claim that native large herbivores have different impacts on ecosystems, specifically plant communities in this case, than their non-native counterparts. Therefore, we should study the ecological roles these animals - native or not - play in ecosystems rather than judge them based on their belonging.’

However, the researchers did find that the traits of megafauna influenced how they affect plants, regardless of nativeness. In particular, small-bodied picky-eaters, such as deer, tended to suppress plant diversity while larger, generalist bulk-feeders such as buffalo tended to increase plant diversity. This is because large, bulk-feeders are physically unable to selectively feed on their favourite plants and are therefore more likely to suppress dominant species, making space for smaller sub-dominant plant species.

The researchers also found that the body mass of individual animals had a significant effect, but not the combined weight of animals on the landscape. This testifies to the unique effects of large and very large animals, compared with smaller animals.

Dr Kristensen added: ‘While one elephant can push over a mid-sized tree, 50 red deer cannot. You can’t total the body mass to understand the effect of animal presence on the landscape, you have to consider the effect of each animal species present.’

The authors point out that the study specifically assessed large mammal herbivores, and that nativeness may remain an important way to understand other types of ecological interactions. For instance, more specialised introduced species such as introduced tree pests, may have really distinct effects on ecosystems because native species did not coevolve with them.

Millions of dollars are spent eradicating animals each year due to our perception of them not belonging in a certain place. Paradoxically, many of those animals are endangered in their home ranges and therefore at risk of diminishing if we were to be successful with the eradication where they are perceived invasive.

Senior author, Professor Jens-Christian Svenning (Aarhus University) added: ‘This interpretation suggests that functional niches vacated by extinctions and extirpations in recent prehistory, often due to humans, are better refilled with animals with similar functional traits as the ones that were lost even if these new species are non-native or feral.’

Introducing large animals to replace extinct ones that performed crucial ecosystem functions is becoming a popular conservation practice, including in the UK and the rest of Europe. According to the researchers, the new study lends support to this as an adaptive conservation approach, which focuses on re-establishing functions rather than concepts of belonging.

Lead author Dr Erick Lundgren (Aarhus University) said: ‘Our findings suggest it is time to start using the same standards to understand the effects of native and introduced organisms alike and to consider seriously the implications of eradication and culling programs that are based on cultural notions of “belonging.” Instead, introduced animals should be studied in the same way as any native wildlife, through the lens of functional ecology.’

Notes to editors:

For media inquiries and interview requests, contact:

Dr Jeppe Kristensen aagaard1986@gmail.com

Dr Erick Lundgren erick.lundgren@gmail.com

The study ‘Functional traits—not nativeness—shape the effects of large mammalian herbivores on plant communities’ will be published in Science at 14:00 ET/ 19:00 GMT Thursday 1 February at https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.adh2616v. This link after the embargo lifts. To view a copy of the paper before this, contact scipak@aaas.org

About the University of Oxford

Oxford University has been placed number 1 in the Times Higher Education World University Rankings for the eighth year running, and number 3 in the QS World Rankings 2024. At the heart of this success are the twin-pillars of our ground-breaking research and innovation and our distinctive educational offer.

Oxford is world-famous for research and teaching excellence and home to some of the most talented people from across the globe. Our work helps the lives of millions, solving real-world problems through a huge network of partnerships and collaborations. The breadth and interdisciplinary nature of our research alongside our personalised approach to teaching sparks imaginative and inventive insights and solutions.

Through its research commercialisation arm, Oxford University Innovation, Oxford is the highest university patent filer in the UK and is ranked first in the UK for university spinouts, having created more than 300 new companies since 1988. Over a third of these companies have been created in the past five years. The university is a catalyst for prosperity in Oxfordshire and the United Kingdom, contributing £15.7 billion to the UK economy in 2018/19, and supports more than 28,000 full time jobs.

END

New study suggests culling animals who ‘don’t belong’ can be a flawed nature conservation practice

2024-02-01

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

IU surgeon-scientist studying physiological effect of microorganisms in sinuses of chronic rhinosinusitis patients

2024-02-01

INDIANAPOLIS—An Indiana University School of Medicine surgeon-scientist is leading a multi-institutional grant investigating the role of the sinus microbiome in chronic rhinosinusitis, an inflammatory disease that causes the lining of the sinuses to swell. The research team will study biospecimens from human sinus surgery patients in the lab and examine how bacteria in the microbiome shape the disease process and might offer novel therapeutic strategies.

Vijay Ramakrishnan, MD, professor of otolaryngology—head ...

Stand Up to Cancer announces changes to scientific advisory committee

2024-02-01

LOS ANGELES – February 1, 2024 – Stand Up To Cancer® (SU2C) today announced changes to its Scientific Advisory Committee (SAC), which oversees SU2C’s scientific research.

Composed of cancer research leaders from academic, government, industry, and advocacy fields, SU2C’s SAC sets direction for research initiatives, reviews proposals for new grant awards, and conducts rigorous oversight of all active grants in the SU2C research portfolio in collaboration with SU2C’s president and CEO Julian Adams, Ph.D.

World renowned cancer researcher and Nobel laureate Phillip A. Sharp, Ph.D., who has chaired the SAC since SU2C launched in ...

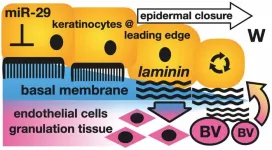

Small RNAs take on the big task of helping skin wounds heal better and faster with minimal scarring

2024-02-01

Philadelphia, February 1, 2024 – New findings in The American Journal of Pathology, published by Elsevier, report that a class of small RNAs (microRNAs), microRNA-29, can restore normal skin structure rather than producing a wound closure by a connective tissue (scar). Any improvement of normal skin repair would benefit many patients affected by large-area or deep wounds prone to dysfunctional scarring.

Because the burden of non-healing wounds is so significant, it is sometimes called a “silent pandemic.” Worldwide, costs associated with wound care are expected to ...

Rural placements for medical students feed ‘pipeline’ for new family docs

2024-02-01

EDMONTON — New research shows an innovative education program is helping to address Alberta’s rural doctor shortage by making it more likely medical students will set up a rural family practice after graduation.

The University of Alberta was one of the first medical schools in Canada to set up its Rural Integrated Community Clerkship program back in 2007. It sends up to 25 third-year students for 10-month intensive work experiences with a single or small number of teaching physicians.

Instead of rotating to a new specialty placement every four to six weeks as in an urban ...

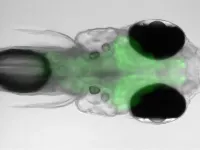

Zebrafish navigate to find their comfortable temperature

2024-02-01

All animals need to regulate their body temperature and cannot survive for long if it gets too high or too low. Warm-blooded organisms like humans have various ways to do this. They release heat by sweating or expanding the blood vessels in their skin, while shivering or burning fat in their brown adipose tissue has the opposite effect.

Cold-blooded animals such as the zebrafish, by contrast, cannot do any of these, so they have a different strategy. They look for places nearby that are at their “comfortable temperature,” just like how we might go out into the sun when we feel chilly or seek out some shade once it gets too ...

Buck scientists discover a potential way to repair synapses damaged in Alzheimer’s disease

2024-02-01

While newly approved drugs for Alzheimer’s show some promise for slowing the memory-robbing disease, the current treatments fall far short of being effective at regaining memory. What is needed are more treatment options targeted to restore memory, said Buck Assistant Professor Tara Tracy, PhD, the senior author of a study that proposes an alternate strategy for reversing the memory problems that accompany Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias.

Since most current research on potential treatments for Alzheimer’s focuses on reducing the toxic proteins, such as tau and amyloid beta, that accumulate in ...

Researchers identify critical pathway responsible for melanoma drug resistance

2024-02-01

(Boston)—One of the major challenges in cancer research and clinical care is understanding the molecular basis for therapeutic resistance as a major cause of long term treatment failures. In cases of melanoma, the main targeted therapeutic strategy is directed against the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway. Unfortunately, in the vast majority of these patients, resistance to MAPK inhibitor therapies develops within one year of treatment.

In a new study from Boston University Chobanian & Avedisian School of Medicine, ...

Pandemic lockdowns and water quality: a revealing study on building usage

2024-02-01

During the COVID-19 pandemic, lower occupancy in buildings led to reduced water use, raising concerns about water quality due to stagnation. Government warnings highlighted increased risks of chemical and microbiological contamination in water systems. Studies showed that reduced usage and stagnation could elevate heavy metal levels and decrease disinfectant effectiveness, affecting microbial growth. To address this, regular fixture flushing was recommended, which temporarily improved water quality but also revealed the complexities of managing building water systems effectively.

In a recent study (https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ese.2023.100314) ...

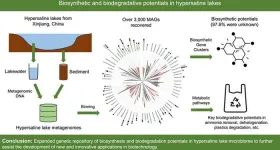

Exploring the unseen: microbial wonders in earth's saltiest waters

2024-02-01

The study delves into hypersaline lakes in Xinjiang, China, exploring the genetic and metabolic diversity of microbial communities termed "microbial dark matters". Hypersaline lake ecosystems, characterized by extreme salinity, harbor unique microorganisms with largely unexplored biosynthesis and biodegradation capabilities. The research seeks to uncover novel biological compounds and pathways, potentially revolutionizing biotechnology, medicine, and environmental remediation by tapping into the untapped potential of these extremophiles.

A recent study (https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ese.2023.100359) published ...

As cancer therapies improve, more patients with rectal cancer forego surgery

2024-02-01

While surgery to remove rectal cancer can be necessary and lifesaving, it can sometimes come with significant drawbacks, like loss of bowel control. According to a study led by Wilmot Cancer Institute researchers, patients with rectal cancer who respond well to radiation and chemotherapy are increasingly foregoing surgery and opting for a watch-and-wait approach.

The study, published in JAMA Oncology, shows that the number of patients opting out of surgery rose nearly 10 percent between 2006 and 2020. These data reflect a shift toward what ...