(Press-News.org) Lincoln, Nebraska, Feb. 19, 2024 — A Husker research duo was named a first-round winner in a National Institutes of Health competition aimed at generating solutions for delivering genome-editing technology to the cells of people with rare and common diseases.

Janos Zempleni, Willa Cather Professor of molecular nutrition, and Jiantao Guo, professor of chemistry, were selected as Phase 1 winners in the NIH’s Targeted Genome Editor Delivery Challenge. The challenge is a three-phase competition with prizes totaling $6 million; the University of Nebraska–Lincoln team was among 30 initial recipients announced in December 2023.

With the $25,000 prize, Zempleni and Guo will advance development of universal milk exosomes — natural nanoparticles contained in milk — capable of transporting gene editors to any location in the body.

These programmable exosomes would be safe, scalable and, unlike conventional nanoparticles, capable of evading macrophages, the immune system cells that destroy foreign substances.

“With our technology, you could treat basically any disease known to mankind, both rare and common,” said Zempleni, who is leading the project and directs the Nebraska Center for the Prevention of Obesity Diseases through Dietary Molecules. “Federal agencies are not overly eager to invest in treatment of rare diseases because it costs a lot of money, yet only a few people benefit.

“With the flexibility of our technology, we can, without extra cost, provide a platform to treat everything, from common diseases like brain cancer, to very rare gene mutations that maybe affect only 500 people in the United States.”

The technology would overcome one of the most significant challenges to using gene editing to treat disease. Though tools like CRISPR-cas9 can delete, repair or replace disease-causing DNA — which could halt tumor growth in cancer or shut down production of harmful proteins — there is currently no reliable means of guaranteeing an editor will reach whichever organ or tissues are associated with a certain disease. And, when gene editors do reach the intended target, they often do not survive in sufficient numbers to change the course of the disease.

The Husker team’s solution combines Zempleni’s nationally recognized expertise in milk exosomes with Guo’s extensive skills in the growing field of bioorthogonal chemistry. Based on his previous research, Zempleni knew it was possible to load milk exosomes with therapeutics and deploy them to a specific tissue in the body. He’s also demonstrated the exosomes’ biological safety, meaning they’re unlikely to cause adverse reactions in patients.

But his tools lacked versatility: He needed a method for directing the exosomes to different locations depending on the disease at hand.

To accomplish this, Zempleni developed an approach that allows him to attach three peptides — short amino acid chains — to the membrane of each exosome. One is a homing peptide, which directs the exosome to bind to a specific site in the body. Another is a “do not eat me” peptide, which sends biochemical signals that allow the exosome to thwart macrophage destruction. The last is what is called a retrofusion peptide, which fortifies the exosome’s survivability once it enters the target cells.

Using the three peptides in concert is novel, Zempleni said, and preliminary data indicate the approach is feasible. But what iss even more innovative is the team’s approach for anchoring the peptides to the exosome membrane. Conventional approaches insert lipid anchors into the membrane, then attach the peptide modifiers to those anchors. The problem is that those lipids are attracted to other lipophilic compounds in the body, leading to detachment and loss of the attached peptide.

The Nebraska team’s approach overcomes this problem by creating docking sites in a membrane protein called CD81, which is firmly rooted in the exosome, preventing detachment. Guo is using bioorthogonal chemistry approaches to create stable, covalent links between the docking sites and the peptides. He said this attachment scheme confers stability and uniformity to the exosome structure, boosting the commercial viability of milk exosome-based therapeutics.

“If this were to go to clinical trials, it will be easier for the FDA to see that this is a defined, homogenous structure, rather than random labeling that would lead to batch-to-batch differences,” said Guo, who leads the Nebraska Center for Integrated Biomolecular Communication.

Zempleni and Guo are also attaching a polyhistidine tag to the exosomes, which allows them to be purified at a low cost and a high purity. The tag is easily removable in case it causes adverse reactions in patients.

Packaging the milk exosomes with CRISPR-cas9 cargo and other therapeutics is one of Zempleni’s longer-term goals. Eventually — possibly with support from additional funding through the TARGETED Challenge — he aims to partner with a transgenic livestock expert at Utah State University to develop a goat or cow that, through its milk, secretes massive numbers of programmable exosomes containing gene-editing cargo and the peptide docking sites.

For this Phase 1 project, he will load cultured MAC-T cells, which closely mirror cow milk cells, with gene-editing tools using previously established genetics and chemistry approaches.

Zempleni and Guo’s designer exosomes are already showing commercial potential. At the end of 2023, the team was notified they would receive a patent titled Extracellular Vesicles and Methods of Using. They have licensed the inventions in that patent to a private company, which is partnering with Roche, Inc., to use bovine milk exosome technology to deliver RNA therapeutics to brain tumors.

The researchers are preparing their application for the TARGETED Challenge Phase 2, which will award up to 10 winners $250,000 and eligibility to compete in Phase 3. NIH will announce Phase 2 winners in April 2025.

END

Husker team wins prize in contest to treat disease through gene editing

2024-02-19

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Why two prehistoric sharks found in Ohio got new names

2024-02-19

COLUMBUS, Ohio – Until recently, Orthacanthus gracilis could have been considered the “John Smith” of prehistoric shark names, given how common it was.

Three different species of sharks from the late Paleozoic Era – about 310 million years ago – were mistakenly given that same name, causing lots of grief to paleontologists who studied and wrote about the sharks through the years and had trouble keeping them apart.

But now Loren Babcock, a professor of earth sciences at The Ohio State University, has finished the arduous task of renaming two of the three sharks – and in the process rediscovered a wealth ...

Study reveals five common ways in which the health of homeless pet owners and their companions is improved

2024-02-19

A rapid scoping review has been conducted which reveals five common ways in which the health of homeless pet owners and their companion animals is improved.

Ten percent of homeless people keep pets. But little information exists on specific intervention strategies for improving the health of homeless people and their pets who are often the only source of unconditional love or companionship in their life.

The study, published in the Human-Animal Interactions journal, found that the most common ways ...

Potassium depletion in soil threatens global crop yields

2024-02-19

Potassium deficiency in agricultural soils is a largely unrecognised but potentially significant threat to global food security if left unaddressed, finds new research involving researchers at UCL, University of Edinburgh and the UK Centre for Ecology & Hydrology.

The study, published in Nature Food, found that more potassium is being removed from agricultural soils than is being added, throughout many regions of the world. It also gives a series of recommendations for how to mitigate the issue.

Potassium is a vital nutrient for plant growth that ...

Poorly coiled frog guts help scientists unravel prevalent human birth anomaly

2024-02-19

How does our intestine, which can be at least 15 feet long, fit properly inside our bodies? As our digestive system grows, the gut tube goes through a series of dramatic looping and rotation to package the lengthening intestine. Failure of the gut to rotate properly during development results in a prevalent, but poorly understood, birth anomaly called intestinal malrotation. Now, in a study published in the journal Development, scientists from North Carolina State University have uncovered a potential cause of this life-threatening condition.

Intestinal malrotation affects 1 in 500 births but the underlying causes are not well understood. ...

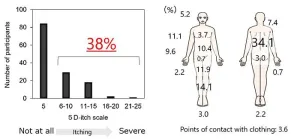

Unveiling uremic toxins linked to itching in hemodialysis patients

2024-02-19

Niigata, Japan – Dr. Yamamoto et al. found the several uremic toxins as one of causes of itching in hemodialysis patients. Hemodialysis patients commonly experience itching on a daily basis, which is distributed throughout their bodies. They developed a "PBUT score" based on highly protein-bound uremic toxins (PBUT) that increase in the body with end-stage kidney disease. The PBUT score was associated with itching in hemodialysis patients.

I. Background of the Study

Patients with advanced chronic kidney disease (CKD) require kidney replacement therapy, such as hemodialysis, to manage their condition. Hemodialysis patients often experience various symptoms, ...

Communities must get prepared for increased flooding due to climate change, expert warns

2024-02-19

Communities must be better prepared for flooding in their homes and businesses, an expert warns, as climate change predictions suggest more extreme flooding globally.

Floods still inflict major costs to the economies, livelihoods and wellbeing of communities, with flood risks and impacts set to increase further due to climate change (IPCC, 2021).

Professor of Environmental Management, Lindsey McEwen explains how many experts now believe local communities have critical roles as key actors within flood risk management and disaster risk reduction.

Professor McEwen, author of Flood ...

Giant Antarctic sea spiders reproductive mystery solved by UH researchers

2024-02-18

Link to video and sound (details below): https://spaces.hightail.com/receive/JwM0o5gQdq

The reproduction of giant sea spiders in Antarctica has been largely unknown to researchers for more than 140 years, until now. University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa scientists traveled to the remote continent and saw first-hand the behaviors of these mysterious creatures, and their findings could have wider implications for marine life and ocean ecosystems in Antarctica and around the world.

Sea spiders, or ...

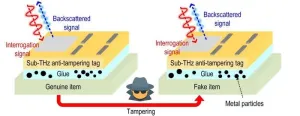

This tiny, tamper-proof ID tag can authenticate almost anything

2024-02-18

A few years ago, MIT researchers invented a cryptographic ID tag that is several times smaller and significantly cheaper than the traditional radio frequency tags (RFIDs) that are often affixed to products to verify their authenticity.

This tiny tag, which offers improved security over RFIDs, utilizes terahertz waves, which are smaller and travel much faster than radio waves. But this terahertz tag shared a major security vulnerability with traditional RFIDs: A counterfeiter could peel the tag off a genuine item and reattach it to a fake, and the authentication system would be none the wiser.

The researchers have now surmounted ...

Viruses that can help ‘dial up’ carbon capture in the sea

2024-02-17

DENVER – Armed with a catalog of hundreds of thousands of DNA and RNA virus species in the world’s oceans, scientists are now zeroing in on the viruses most likely to combat climate change by helping trap carbon dioxide in seawater or, using similar techniques, different viruses that may prevent methane’s escape from thawing Arctic soil.

By combining genomic sequencing data with artificial intelligence analysis, researchers have identified ocean-based viruses and assessed their genomes to find that they “steal” genes from other microbes or cells that process carbon in the sea. Mapping microbial ...

Imageomics poised to enable new understanding of life

2024-02-17

Embargoed until 1:30 p.m. ET, Saturday Feb. 17, 2024

DENVER – Imageomics, a new field of science, has made stunning progress in the past year and is on the verge of major discoveries about life on Earth, according to one of the founders of the discipline.

Tanya Berger-Wolf, faculty director of the Translational Data Analytics Institute at The Ohio State University, outlined the state of imageomics in a presentation on Feb. 17, 2024, at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

“Imageomics ...