(Press-News.org) COLUMBUS, Ohio – Until recently, Orthacanthus gracilis could have been considered the “John Smith” of prehistoric shark names, given how common it was.

Three different species of sharks from the late Paleozoic Era – about 310 million years ago – were mistakenly given that same name, causing lots of grief to paleontologists who studied and wrote about the sharks through the years and had trouble keeping them apart.

But now Loren Babcock, a professor of earth sciences at The Ohio State University, has finished the arduous task of renaming two of the three sharks – and in the process rediscovered a wealth of fossil fishes that had been stored at an Ohio State museum for years but had been largely forgotten.

In order to change the names, Babcock had to go through a process governed by the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN). He had to document the need to change the names, propose new names and submit them to an ICZN-recognized journal for peer review and then have the ICZN officially accept the names.

“It was one of the most complex naming problems we have had in paleontology, which is probably one reason no one attempted to fix it until now,” Babcock said.

“A lot of scientists in the field have written, thanking me for doing this. We are all happy it is finally done,” he said.

One measure of the impact the renaming has had on the field: Babcock’s paper announcing the new names was just published in the journal ZooKeys on Jan. 8, but it has already been referenced on seven different Wikipedia pages.

The original Orthacanthus gracilis fossil was found in Germany and named in 1848. That species gets to keep the name.

The remaining two fossils were found in Ohio and named by the famous American paleontologist John Strong Newberry in 1857 and 1875.

Babcock renamed the Ohio sharks Orthacanthus lintonensis and Orthacanthus adamas, both based on the name of the place where they were originally found.

Why did Newberry give the two Ohio sharks the same name?

“He probably just forgot. It was nearly 20 years between the time the two species were named,” Babcock said.

And as far as giving it the same name as a German species: “In those days, it was really difficult to search for names that were already in existence – they did not have the internet.”

The sharks themselves were fascinating creatures, Babcock said. They were large and creepy, nearly 10 feet long, and looked more like eels than present-day sharks, with long dorsal fins extending the length of their backs and a peculiar spine extending backward from their heads.

They lived in the fresh or brackish water of what are known as “coal swamps” of the late Carboniferous Period (323-299 million years ago) during the late Paleozoic Era. They belong to an extinct group of chondrichthyans (which includes sharks, skates and rays) called the xenacanthiforms.

Newberry was for a time the chief geologist at the Geological Survey of Ohio. He played an important role in the early growth of what is now the Orton Geological Museum at Ohio State.

Babcock, who is the current director of the Orton Museum, decided to begin the renaming process after reviewing the museum’s collection. He was surprised to see how many fossils the museum had that had been collected by Newberry, including the two prehistoric sharks.

Babcock wrote about Orton’s Newberry collection in a new article published in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology.

Through the years, scientists have written about how various Newberry specimens had been lost. It turns out many had been at the Orton Museum.

“No museum has a larger collection of Newberry’s fossils except for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City,” Babcock said.

“Not a lot of people are aware of that – I did not even know the extent of our collection. If you’re looking for part of the Newberry collection and can’t find it in the American Museum of Natural History, it is probably going to be here.”

END

Why two prehistoric sharks found in Ohio got new names

Research leads to rediscovery of forgotten fossils

2024-02-19

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Study reveals five common ways in which the health of homeless pet owners and their companions is improved

2024-02-19

A rapid scoping review has been conducted which reveals five common ways in which the health of homeless pet owners and their companion animals is improved.

Ten percent of homeless people keep pets. But little information exists on specific intervention strategies for improving the health of homeless people and their pets who are often the only source of unconditional love or companionship in their life.

The study, published in the Human-Animal Interactions journal, found that the most common ways ...

Potassium depletion in soil threatens global crop yields

2024-02-19

Potassium deficiency in agricultural soils is a largely unrecognised but potentially significant threat to global food security if left unaddressed, finds new research involving researchers at UCL, University of Edinburgh and the UK Centre for Ecology & Hydrology.

The study, published in Nature Food, found that more potassium is being removed from agricultural soils than is being added, throughout many regions of the world. It also gives a series of recommendations for how to mitigate the issue.

Potassium is a vital nutrient for plant growth that ...

Poorly coiled frog guts help scientists unravel prevalent human birth anomaly

2024-02-19

How does our intestine, which can be at least 15 feet long, fit properly inside our bodies? As our digestive system grows, the gut tube goes through a series of dramatic looping and rotation to package the lengthening intestine. Failure of the gut to rotate properly during development results in a prevalent, but poorly understood, birth anomaly called intestinal malrotation. Now, in a study published in the journal Development, scientists from North Carolina State University have uncovered a potential cause of this life-threatening condition.

Intestinal malrotation affects 1 in 500 births but the underlying causes are not well understood. ...

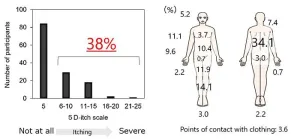

Unveiling uremic toxins linked to itching in hemodialysis patients

2024-02-19

Niigata, Japan – Dr. Yamamoto et al. found the several uremic toxins as one of causes of itching in hemodialysis patients. Hemodialysis patients commonly experience itching on a daily basis, which is distributed throughout their bodies. They developed a "PBUT score" based on highly protein-bound uremic toxins (PBUT) that increase in the body with end-stage kidney disease. The PBUT score was associated with itching in hemodialysis patients.

I. Background of the Study

Patients with advanced chronic kidney disease (CKD) require kidney replacement therapy, such as hemodialysis, to manage their condition. Hemodialysis patients often experience various symptoms, ...

Communities must get prepared for increased flooding due to climate change, expert warns

2024-02-19

Communities must be better prepared for flooding in their homes and businesses, an expert warns, as climate change predictions suggest more extreme flooding globally.

Floods still inflict major costs to the economies, livelihoods and wellbeing of communities, with flood risks and impacts set to increase further due to climate change (IPCC, 2021).

Professor of Environmental Management, Lindsey McEwen explains how many experts now believe local communities have critical roles as key actors within flood risk management and disaster risk reduction.

Professor McEwen, author of Flood ...

Giant Antarctic sea spiders reproductive mystery solved by UH researchers

2024-02-18

Link to video and sound (details below): https://spaces.hightail.com/receive/JwM0o5gQdq

The reproduction of giant sea spiders in Antarctica has been largely unknown to researchers for more than 140 years, until now. University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa scientists traveled to the remote continent and saw first-hand the behaviors of these mysterious creatures, and their findings could have wider implications for marine life and ocean ecosystems in Antarctica and around the world.

Sea spiders, or ...

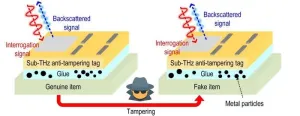

This tiny, tamper-proof ID tag can authenticate almost anything

2024-02-18

A few years ago, MIT researchers invented a cryptographic ID tag that is several times smaller and significantly cheaper than the traditional radio frequency tags (RFIDs) that are often affixed to products to verify their authenticity.

This tiny tag, which offers improved security over RFIDs, utilizes terahertz waves, which are smaller and travel much faster than radio waves. But this terahertz tag shared a major security vulnerability with traditional RFIDs: A counterfeiter could peel the tag off a genuine item and reattach it to a fake, and the authentication system would be none the wiser.

The researchers have now surmounted ...

Viruses that can help ‘dial up’ carbon capture in the sea

2024-02-17

DENVER – Armed with a catalog of hundreds of thousands of DNA and RNA virus species in the world’s oceans, scientists are now zeroing in on the viruses most likely to combat climate change by helping trap carbon dioxide in seawater or, using similar techniques, different viruses that may prevent methane’s escape from thawing Arctic soil.

By combining genomic sequencing data with artificial intelligence analysis, researchers have identified ocean-based viruses and assessed their genomes to find that they “steal” genes from other microbes or cells that process carbon in the sea. Mapping microbial ...

Imageomics poised to enable new understanding of life

2024-02-17

Embargoed until 1:30 p.m. ET, Saturday Feb. 17, 2024

DENVER – Imageomics, a new field of science, has made stunning progress in the past year and is on the verge of major discoveries about life on Earth, according to one of the founders of the discipline.

Tanya Berger-Wolf, faculty director of the Translational Data Analytics Institute at The Ohio State University, outlined the state of imageomics in a presentation on Feb. 17, 2024, at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

“Imageomics ...

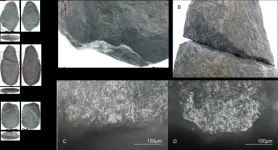

Scientists try out stone age tools to understand how they were used

2024-02-17

Tokyo, Japan – Researchers from Tokyo Metropolitan University crafted replica stone age tools and used them for a range of tasks to see how different activities create traces on the edge. They found that a combination of macroscopic and microscopic traces can tell us how stone edges were used. Their criteria help separate tools used for wood-felling from other activities. Dated stone edges may be used to identify when timber use began for early humans.

For prehistoric humans, improvements in woodworking technology were revolutionary. While Paleolithic (early stone age) artifacts point to the use of wood for simple tools such as spears ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

New knowledge on heritability paves the way for better treatment of people with chronic inflammatory bowel disease

Under the Lens: Microbiologists Nicola Holden and Gil Domingue weigh in on the raw milk debate

Science reveals why you can’t resist a snack – even when you’re full

Kidney cancer study finds belzutifan plus pembrolizumab post-surgery helps patients at high risk for relapse stay cancer-free longer

Alkali cation effects in electrochemical carbon dioxide reduction

Test platforms for charging wireless cars now fit on a bench

$3 million NIH grant funds national study of Medicare Advantage’s benefit expansion into social supports

Amplified Sciences achieves CAP accreditation for cutting-edge diagnostic lab

Fred Hutch announces 12 recipients of the annual Harold M. Weintraub Graduate Student Award

Native forest litter helps rebuild soil life in post-mining landscapes

Mountain soils in arid regions may emit more greenhouse gas as climate shifts, new study finds

Pairing biochar with other soil amendments could unlock stronger gains in soil health

Why do we get a skip in our step when we’re happy? Thank dopamine

UC Irvine scientists uncover cellular mechanism behind muscle repair

Platform to map living brain noninvasively takes next big step

Stress-testing the Cascadia Subduction Zone reveals variability that could impact how earthquakes spread

We may be underestimating the true carbon cost of northern wildfires

Blood test predicts which bladder cancer patients may safely skip surgery

Kennesaw State's Vijay Anand honored as National Academy of Inventors Senior Member

Recovery from whaling reveals the role of age in Humpback reproduction

Can the canny tick help prevent disease like MS and cancer?

Newcomer children show lower rates of emergency department use for non‑urgent conditions, study finds

Cognitive and neuropsychiatric function in former American football players

From trash to climate tech: rubber gloves find new life as carbon capturers materials

A step towards needed treatments for hantaviruses in new molecular map

Boys are more motivated, while girls are more compassionate?

Study identifies opposing roles for IL6 and IL6R in long-term mortality

AI accurately spots medical disorder from privacy-conscious hand images

Transient Pauli blocking for broadband ultrafast optical switching

Political polarization can spur CO2 emissions, stymie climate action

[Press-News.org] Why two prehistoric sharks found in Ohio got new namesResearch leads to rediscovery of forgotten fossils