(Press-News.org) More than 100 million years ago, the ancestors of the first snakes were small lizards that lived alongside other small, nondescript lizards in the shadow of the dinosaurs.

Then, in a burst of innovation in form and function, the ancestors of snakes evolved legless bodies that could slither across the ground, highly sophisticated chemical detection systems to find and track prey, and flexible skulls that enabled them to swallow large animals.

Those changes set the stage for the spectacular diversification of snakes over the past 66 million years, allowing them to quickly exploit new opportunities that emerged after an asteroid impact wiped out roughly three-quarters of the planet's plant and animal species.

But what triggered the evolutionary explosion of snake diversity—a phenomenon known as adaptive radiation—that led to nearly 4,000 living species and made snakes one of evolution's biggest success stories?

A large new genetic and dietary study of snakes, from an international team led by University of Michigan biologists, suggests that speed is the answer. Snakes evolved up to three times faster than lizards, with massive shifts in traits associated with feeding, locomotion and sensory processing, according to the study scheduled for online publication Feb. 22 in the journal Science.

"Fundamentally, this study is about what makes an evolutionary winner. We found that snakes have been evolving faster than lizards in some important ways, and this speed of evolution has let them take advantage of new opportunities that other lizards could not," said University of Michigan evolutionary biologist Daniel Rabosky, senior author of the upcoming Science paper.

"Snakes evolved faster and—dare we say it—better than some other groups. They are versatile and flexible and able to specialize on prey that other groups cannot use," said Rabosky, a curator at the U-M Museum of Zoology and a professor in the Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology.

For the study, researchers generated the largest, most comprehensive evolutionary tree of snakes and lizards by sequencing partial genomes for nearly 1,000 species. In addition, they compiled a huge dataset on lizard and snake diets, examining records of stomach contents from tens of thousands of preserved museum specimens.

They fed this mountain of data into sophisticated mathematical and statistical models, backed by massive amounts of computer power, to analyze the history of snake and lizard evolution through geological time and to study how various traits, such as limblessness, evolved.

This multipronged approach revealed that while other reptiles have evolved many snakelike traits—25 different groups of lizards also lost their limbs, for instance—only snakes experienced this level of explosive diversification.

Take Australia's legless gecko, for example.

Like snakes, this lizard lost its legs and evolved a flexible skull. Yet the creature has barely diversified over millions of years. No evolutionary explosion—just a couple of species scraping out a living in the Australian outback.

So, it seems there is something special about snakes that enabled them to hit the evolutionary jackpot. Maybe something in their genes that allowed them to be evolutionarily flexible while other groups of organisms are much more constrained.

"A standout aspect of snakes is how ecologically diverse they are: burrowing

underground, living in freshwater, the ocean and almost every conceivable habitat on land," said Alexander Pyron, study co-author and an associate professor of biology at George Washington University. "While some lizards do some of these things—and there are many more lizards than snakes—there are many more snakes in most of these habitats in most places."

The ultimate causes, or triggers, of adaptive radiations is one of the big mysteries in biology. In the case of snakes, it's likely there were multiple contributing factors, and it may never be possible to tease them apart.

The authors of the upcoming Science study refer to this once-in-evolutionary-history event as a macroevolutionary singularity with "unknown and perhaps unknowable" causes.

A macroevolutionary singularity can be viewed as a sudden shift into a higher evolutionary gear, and biologists suspect these outbursts have happened repeatedly throughout the history of life on Earth. The sudden emergence and subsequent dominance of flowering plants is another example.

In the case of snakes, the singularity started with the nearly simultaneous (from an evolutionary perspective) acquisition of elongated legless bodies, advanced chemical detection systems and flexible skulls.

Those crucial changes allowed snakes, as a group, to pursue a much broader array of prey types, while simultaneously enabling individual species to evolve extreme dietary specialization.

Today, there are cobras that strike with lethal venom, giant pythons that constrict their prey, shovel-snouted burrowers that hunt desert scorpions, slender tree snakes called "goo-eaters" that prey on snails and frog eggs high above the ground, paddle-tailed sea snakes that probe reef crevices for fish eggs and eels, and many more.

"One of our key results is that snakes underwent a profound shift in feeding ecology that completely separates them from other reptiles," Rabosky said. "If there is an animal that can be eaten, it's likely that some snake, somewhere, has evolved the ability to eat it."

For the study, the researchers got an inside look at snake dietary preferences by reviewing field observations and stomach-content records for more than 60,000 snake and lizard specimens, mostly from natural history museums. The contributing museums included the University of Michigan Museum of Zoology, home to the world's largest research collection of snake specimens.

"Museum specimens give us this incredible window into how organisms make a living in nature. For secretive animals like snakes, it's almost impossible to get this kind of data any other way because it's hard to observe a lot of their behavior directly," said study co-lead author Pascal Title of Stony Brook University, who completed his doctorate at U-M in 2018.

The study's 20 authors are from universities and museums in the United States, the United Kingdom, Australia, Brazil and Finland.

"What I love about this study is how it integrates hard-earned field and museum data with new genomic and analytical methods to show a basic biological truth: Snakes are exceptional and frankly quite cool," said co-lead author Sonal Singhal of California State University, Dominguez Hills, who started work on the project as a U-M postdoctoral scholar.

The study was supported by several funding agencies, including multiple grants from the U.S. National Science Foundation. More information, including a copy of the study, is available to registered reporters at https://www.eurekalert.org/press/scipak.

Study: The macroevolutionary singularity of snakes (DOI: 10.1126/science.adh2449) (available when embargo lifts).

Photos

END

Snakes do it faster, better: How a group of scaly, legless lizards hit the evolutionary jackpot

2024-02-22

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Side effects of wide scale forestation could reduce carbon removal benefits by up to a third

2024-02-22

The side effects of large-scale forestation initiatives could reduce the CO2 removal benefits by up to a third

Researchers at the University of Sheffield used computer models, which simulate the land, ocean and atmosphere, to investigate the impact of forestation under future climate scenarios

While forestation increases atmospheric CO2 removal, it also changes atmospheric composition and darkens the land surface, reducing its potential to tackle climate change

Combining forestation with other climate mitigation ...

Yale chemists synthesize unique anticancer molecules using novel approach

2024-02-22

New Haven, Conn. — Nearly 30 years ago, scientists discovered a unique class of anticancer molecules in a family of bryozoans, a phylum of marine invertebrates found in tropical waters.

The chemical structures of these molecules, which consist of a dense, highly complex knot of oxidized rings and nitrogen atoms, has attracted the interest of organic chemists worldwide, who aimed to recreate these structures from scratch in the laboratory. However, despite considerable effort, it has remained an elusive task. Until now, that is.

A team of Yale chemists, writing in the journal Science, ...

Maynooth University partners in study published in Science that finds evidence of elusive neutron star

2024-02-22

A new study, published in Science and co-authored by Dr Patrick Kavanagh of Maynooth University’s Department of Experimental Physics in Ireland, has provided the first conclusive evidence for the presence of the elusive neutron star produced in the supernova SN 1987A.

Supernovae are the spectacular end result of the collapse of stars more massive than eight to ten times the mass of the sun. Besides being the main sources of chemical elements such as the carbon, oxygen, silicon, and iron that make life possible, they are also responsible for creating the ...

James Webb telescope detects traces of neutron star in iconic supernova

2024-02-22

Scientists can finally show that a neutron star formed from our most well-studied supernova, SN 1987A. The breakthrough was made possible thanks to the James Webb telescope.

Supernovae are the spectacular end result of the collapse of stars more massive than 8-10 times the mass of the sun. Besides being the main sources of chemical elements such as carbon, oxygen, silicon, and iron that make life possible, they are also responsible for creating the most exotic objects in the universe, neutron stars and black holes.

In 1987, supernova 1987A (SN 1987A) ...

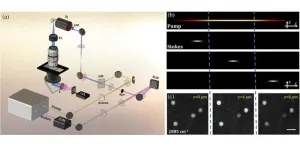

Enhanced 3D chemical imaging with phase-modulation

2024-02-22

Understanding complex biological and biomedical systems is greatly aided by 3D imaging, which provides much more detailed information than traditional two-dimensional methods. However, live cell and tissue imaging remain challenging due to factors like limited imaging speed and significant scattering in turbid environments.

In this context, multimodal microscopy techniques are notable. Specifically, nonlinear techniques like CRS (coherent Raman scattering) use optical vibrational spectroscopy, providing precise chemical imaging in tissues and cells in a label-free way. Furthermore, stimulated Raman scattering (SRS) ...

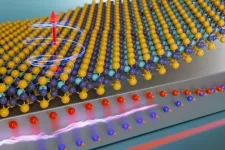

Researchers harness 2D magnetic materials for energy-efficient computing

2024-02-22

CAMBRIDGE, MA — Experimental computer memories and processors built from magnetic materials use far less energy than traditional silicon-based devices. Two-dimensional magnetic materials, composed of layers that are only a few atoms thick, have incredible properties that could allow magnetic-based devices to achieve unprecedented speed, efficiency, and scalability.

While many hurdles must be overcome until these so-called van der Waals magnetic materials can be integrated into functioning computers, MIT researchers took an important step in this direction by demonstrating precise control of a van der ...

Empowering autistic teens: New clinician advice for navigating chronic pain

2024-02-22

When you’re an autistic teenager living with chronic pain, getting treatment for your pain can be a challenging experience. That’s according to a group of young people who’ve spoken to Dr. Abbie Jordan of the Department of Psychology and Centre for Pain Research at The University of Bath about their experiences. Teenagers mention sensory issues, a lack of autism awareness among staff, or feeling “doubly different” compared to their peers, making receiving “one-size-fits-all” psychologically focused treatment for their chronic pain ...

Climate change linked to rise in mental distress among teens, according to Drexel study

2024-02-22

Worsening human-induced climate change may have effects beyond the widely reported rising sea levels, higher temperatures, and impacts on food supply and migration – and may also extend to influencing mental distress among high schoolers in the United States.

According to a representative survey of 38,616 high school students from 22 public school districts in 14 U.S. states, the quarter of those adolescents who had experienced the highest number of days in a climate disaster within the past two years and the past five years – such as hurricanes, floods, tornadoes, droughts, and wildfire – had 20% higher odds of developing mental ...

Combination of group competition and repeated interactions promotes cooperation

2024-02-22

One of the great unresolved mysteries of human evolution is how pro-social, cooperative behavior could have evolved. What led to the establishment of a behavior that prioritizes the benefit of the community over that of the individual in a world where materially successful individuals reproduce, and others slowly perish?

The prevailing theory suggests that this occurred due to repeated interactions. Over generations, humans learned that cooperative behavior pays off in the long run. People collaborate because they anticipate interacting with the same individuals ...

A new beginning: The search for more temperate Tatooines

2024-02-22

New Haven, Conn. — Luke Skywalker’s childhood might have been slightly less harsh if he’d grown up on a more temperate Tatooine — like the ones identified in a new, Yale-led study.

According to the study’s authors, there are more climate-friendly planets in binary star systems — in other words, those with two suns — than previously known. And, they say, it may be a sign that, at least in some ways, the universe leans in the direction of orderly alignment rather than chaotic misalignment.

For the study, ...