(Press-News.org) The blue whale genome was published in the journal Molecular Biology and Evolution, and the Etruscan shrew genome was published in the journal Scientific Data.

Research models using animal cell cultures can help navigate big biological questions, but these tools are only useful when following the right map.

“The genome is a blueprint of an organism,” says Yury Bukhman, first author of the published research and a computational biologist in the Ron Stewart Computational Group at the Morgridge Institute, an independent research organization that works in affiliation with the University of Wisconsin–Madison in emerging fields such as regenerative biology, metabolism, virology and biomedical imaging. “In order to manipulate cell cultures or measure things like gene expression, you need to know the genome of the species — it makes more research possible.”

The Morgridge team’s interest in the blue whale and the Etruscan shrew began with research on the biological mechanisms behind the “developmental clock” from James Thomson, emeritus director of regenerative biology at Morgridge and longtime professor of cell and regenerative bBiology in the UW School of Medicine and Public Health. It’s generally understood that larger organisms take longer to develop from a fertilized egg to a full-grown adult than smaller creatures, but the reason why remains unknown.

“It’s important just for fundamental biological knowledge from that perspective. How do you build such a large animal? How can it function?” says Bukhman.

Bukhman suggests that a practical application of this knowledge is in the emerging area of stem cell-based therapies. To heal an injury, stem cells must differentiate into specialized cell types of the relevant organ or tissue. The speed of this process is controlled by some of the same molecular mechanisms that underlie the developmental clock.

What genomes from animals of different sizes can tell us about our own health

Understanding the genomes of the largest and smallest of mammals may also help unravel the biomedical mystery known as Peto’s paradox. This is a curious phenomenon in which large mammals such as whales and elephants live longer and are less likely to develop cancer — often caused by DNA replication errors that occasionally happen during cell division — despite having a greater number of cells (and therefore more cell divisions) than smaller mammals like humans or mice.

Meanwhile, knowledge of the Etruscan shrew genome will enable new insights in the field of metabolism. The shrew has an extremely high surface to volume ratio and fast metabolic rate. These high energy demands are a product of its tiny size — no bigger than a human thumb and weighing less than a penny — making it an interesting model to better understand regulation of metabolism.

The blue whale and Etruscan shrew genome projects are part of a large collaborative effort involving dozens of contributors from institutions across North America and several European countries, in conjunction with the Vertebrate Genomes Project.

The mission of the VGP is to assemble high-quality reference genomes for all living vertebrate species on Earth. This international consortium of researchers includes top experts in genome assembly and curation.

“The VGP has established a set of methods and criteria for producing a reference genome,” Bukhman says. “Accuracy, contiguity, and completeness are three measures of quality.”

Previous methods to sequence genomes used short read technologies, which produce short lengths of the DNA sequence 150 to 300 base pairs long, called reads. Overlapping reads are then assembled into longer contiguous sequences, called contigs.

Contigs assembled from short reads tend to be relatively small compared to mammalian chromosomes. As a result, draft genomes reconstructed from such contigs tend to be very fragmented and have a lot of gaps.

Instead, the team used long read sequencing, with reads around 10,000 base pairs in length, with the principal advantage being longer contigs and fewer gaps.

“Then you can use other methods such as optical mapping and Hi-C to assemble contigs into bigger structures called scaffolds, and those can be as big as an entire chromosome,” Bukhman explains.

The researchers also analyzed segmental duplications, large regions of duplicated sequence that often contain genes and can provide insight into evolutionary processes when compared to other species, either closely or distantly related.

They found that the blue whale had a large burst of segmental duplications in the recent past, with larger numbers of copies than the bottlenose dolphin and the vaquita (the world’s smallest cetacean, the order of mammals including whales, dolphins and porpoises). While most of the copies of genes created this way are likely non-functional, or their function is still unknown, the team did identify several known genes.

One encodes the protein metallothionein, which is known to bind heavy metals and sequester their toxicity — a useful mechanism for large animals that accumulate heavy metals while living in the ocean.

How reference genomes can help with wildlife conservation

A reference genome is also useful for species conservation. The blue whale was hunted almost to extinction in the first half of the 20th century. It is now protected by an international treaty and the populations are recovering.

“In the world’s oceans, the blue whale is basically everywhere except for the high Arctic. So, if you have a reference genome, then you can make comparisons and can better understand the population structure of the different blue whale groups in different parts of the globe,” Bukhman says. “The blue whale genome is highly heterozygous, there's still a lot of genetic diversity, which has important implications for conservation.”

Which begs the question: how do you go about acquiring samples from a large, endangered creature that exists in the vastness of the oceans?

“The logistics posed several challenges, including the fact that blue whale sightings in our area are very rare and almost unpredictable,” says Susanne Meyer, a research specialist at the University of California Santa Barbara, who spent over a year to coordinate the permits, personnel and resources needed to procure the samples.

Once their local whale-watching team determined the timing and coordinates of the whale sightings, they brought in licensed whale researcher Jeff K. Jacobsen to perform the whale biopsies using an approved standard cetacean skin biopsy technique, which involves a custom stainless steel biopsy tube fitted to a crossbow arrow.

The team acquired samples from four blue whales, which Meyer used to develop and expand fibroblasts in cell culture for the genome sequencing and further research use.

Size doesn't matter when it comes to an animal's genome

While the Etruscan shrew genome wasn’t studied as extensively as the blue whale genome, the team reported an interesting finding.

“We found that there are relatively few segmental duplications in the shrew genome,” Bukhman says, while emphasizing that this result does not necessarily correlate to the diminutive size of the shrew itself. “While shrews belong to a different mammalian order, some similarly small rodents have lots of segmental duplications, and the house mouse is kind of a champion in that sense that it has the most. So, it's not a matter of size.”

As the Vertebrate Genomes Project makes strides in producing more high-quality reference genomes for all vertebrates, Bukhman is hopeful that contributions to those efforts will continue to advance biological research in the future.

These studies were supported by grants from the National Science Foundation (2046753, DBI2003635, DBI2146026, IIS2211598, DMS2151678, CMMI1825941 and MCB1925643) and National Institutes of Health (R01GM133840).

END

All creatures great and small: Sequencing the blue whale and Etruscan shrew genomes

Size doesn’t matter when it comes to genome sequencing in the animal kingdom, as a team of researchers at the Morgridge Institute for Research recently illustrated.

2024-03-18

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

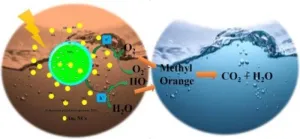

Sustainable solution for wastewater polluted by dyes used in many industries

2024-03-18

Water pollution from dyes used in textile, food, cosmetic and other manufacturing is a major ecological concern with industry and scientists seeking biocompatible and more sustainable alternatives to protect the environment.

A new study led by Flinders University has discovered a novel way to degrade and potentially remove toxic organic chemicals including azo dyes from wastewater, using a chemical photocatalysis process powered by ultraviolet light.

Professor Gunther Andersson, from the Flinders Institute for NanoScale Science and Technology, says the process involves creating metallic ‘clusters’ of just nine gold (Au) atoms chemically ‘anchored’ ...

Food companies’ sponsorship of children’s sports encourages children to buy their products, Canadian research suggests

2024-03-18

*This is an early press release from the European Congress on Obesity (ECO 2024) Venice 12-15 May. Please credit the Congress if using this material*

Food companies’ sponsorship of children’s sports may encourage children to buy their products, new research to be presented at the European Congress on Obesity (ECO 2024) (Venice 12-15 May), has found.

The Canadian research also found that many children view food companies that sponsor or give money to children’s sports as being “generous” ...

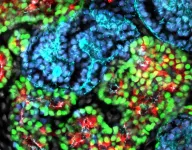

USC receives $3.95 million CIRM grant for organoid resource center

2024-03-18

To democratize access to lab-grown organ-like structures known as organoids and other advanced stem cell and transcriptomic technologies, USC will launch the CIRM ASCEND Center, dedicated to “Advancing Stem Cell Education and Novel Discoveries.” Funded by a $3.95 million grant from the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine (CIRM), the voter-created state agency charged with distributing public funding to support stem cell research and education, ASCEND joins a network of shared resources laboratories ...

New research finds boreal arctic wetlands are producing more methane over time

2024-03-18

MADISON –– Scientists have been measuring global methane emissions for decades, but the boreal arctic —with a wide range of biomes including wetlands that extend across the northern parts of North America, Europe and Asia — is a key region where accurately estimating highly potent greenhouse gas emissions has been challenging.

Wetlands are great at storing carbon, but as global temperatures increase, they are warming up. That causes the carbon they store to be released into the atmosphere in the form of methane, which contributes to more global warming.

Now, researchers — including the University ...

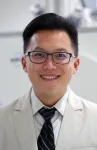

TLI Investigator Dr. Wei Yan named Editor-in-Chief of the Andrology Journal

2024-03-18

The Lundquist Institute is proud to announce that Wei Yan, MD, PhD, a distinguished professor at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA and Lundquist investigator, has been appointed by the American Society of Andrology and the European Academy of Andrology as the new Editor-in-Chief of Andrology, the highly-respected journal in the field of reproductive medicine.

Dr. Yan's appointment to Andrology is a testament to his dedication to reproductive medicine. With extensive editorial experience, including his previous roles as ...

New study reveals insights into COVID-19 antibody response durability

2024-03-18

Researchers at the Institute of Human Virology (IHV) at the University of Maryland School of Medicine published a new study in the Journal of Infectious Diseases investigating the antibody response following SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Long-lived plasma cells are responsible for durable antibody responses that persist for decades after immunization or infection. For example, infection with measles, mumps, rubella, or immunization with vaccines against tetanus or diphtheria elicit antibody responses that can last for many decades. By contrast, other infections and vaccines elicit short-lived antibody responses that last only a few ...

Climate change alters the hidden microbial food web in peatlands

2024-03-18

DURHAM, N.C. -- The humble peat bog conjures images of a brown, soggy expanse. But it turns out to have a superpower in the fight against climate change.

For thousands of years, the world’s peatlands have absorbed and stored vast amounts of carbon dioxide, keeping this greenhouse gas in the ground and not in the air. Although peatlands occupy just 3% of the land on the planet, they play an outsized role in carbon storage -- holding twice as much as all the world’s forests do.

The fate of all that carbon is uncertain in the face of climate change. And ...

Text nudges can increase uptake of COVID-19 boosters– if they play up a sense of ownership of the vaccine

2024-03-18

New research published in Nature Human Behavior suggests that text nudges encouraging people to get the COVID-19 vaccine, which had proven effective in prior real-world field tests, are also effective at prompting people to get a booster.

The key in both cases is to include in the text a sense of ownership in the dose awaiting them.

The paper, led by Hengchen Dai, an associate professor of management and organizations and behavioral decision making at the UCLA Anderson School of Management, and Silvia Saccardo, an associate professor of social and decision sciences at Carnegie Mellon University, draws on previous research published in Nature that examined the effectiveness ...

A new study shows how neurochemicals affect fMRI readings

2024-03-18

CHAPEL HILL, N.C. – The brain is an incredibly complex and active organ that uses electricity and chemicals to transmit and receive signals between its sub-regions.

Researchers have explored various technologies to directly or indirectly measure these signals to learn more about the brain. Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), for example, allows them to detect brain activity via changes related to blood flow.

Yen-Yu Ian Shih, PhD, professor of neurology and associate director of UNC’s Biomedical Research Imaging Center, and his fellow lab members have long been curious about how neurochemicals in the brain regulate and influence neural activity, ...

Digital reminders for flu vaccination improves turnout, but not clinical outcomes in older adults

2024-03-18

Embargoed for release until 5:00 p.m. ET on Monday 18 March 2024

Annals of Internal Medicine Tip Sheet

@Annalsofim

Below please find summaries of new articles that will be published in the next issue of Annals of Internal Medicine. The summaries are not intended to substitute for the full articles as a source of information. This information is under strict embargo and by taking it into possession, media representatives are committing to the terms of the embargo not only on their own behalf, but also on behalf of the organization they represent.

----------------------------

1. Digital reminders for flu vaccination improves ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Why chronic pain lasts longer in women: Immune cells offer clues

Toxic exposure creates epigenetic disease risk over 20 generations

More time spent on social media linked to steroid use intentions among boys and men

New study suggests a “kick it while it’s down” approach to cancer treatment could improve cure rates

Milken Institute, Ann Theodore Foundation launch new grant to support clinical trial for potential sarcoidosis treatment

New strategies boost effectiveness of CAR-NK therapy against cancer

Study: Adolescent cannabis use linked to doubling risk of psychotic and bipolar disorders

Invisible harms: drug-related deaths spike after hurricanes and tropical storms

Adolescent cannabis use and risk of psychotic, bipolar, depressive, and anxiety disorders

Anxiety, depression, and care barriers in adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities

Study: Anxiety, gloom often accompany intellectual deficits

Massage Therapy Foundation awards $300,000 research grant to the University of Denver

Gastrointestinal toxicity linked to targeted cancer therapies in the United States

Countdown to the Bial Award in Biomedicine 2025

Blood marker from dementia research could help track aging across the animal world

Birds change altitude to survive epic journeys across deserts and seas

Here's why you need a backup for the map on your phone

ACS Central Science | Researchers from Insilico Medicine and Lilly publish foundational vision for fully autonomous “Prompt-to-Drug” pharmaceutical R&D

Increasing the number of coronary interventions in patients with acute myocardial infarction does not appear to reduce death rates

Tackling uplift resistance in tall infrastructures sustainably

Novel wireless origami-inspired smart cushioning device for safer logistics

Hidden genetic mismatch, which triples the risk of a life-threatening immune attack after cord blood transplantation

Physical function is a crucial predictor of survival after heart failure

Striking genomic architecture discovered in embryonic reproductive cells before they start developing into sperm and eggs

Screening improves early detection of colorectal cancer

New data on spontaneous coronary artery dissection (SCAD) – a common cause of heart attacks in younger women

How root growth is stimulated by nitrate: Researchers decipher signalling chain

Scientists reveal our best- and worst-case scenarios for a warming Antarctica

Cleaner fish show intelligence typical of mammals

AABNet and partners launch landmark guide on the conservation of African livestock genetic resources and sustainable breeding strategies

[Press-News.org] All creatures great and small: Sequencing the blue whale and Etruscan shrew genomesSize doesn’t matter when it comes to genome sequencing in the animal kingdom, as a team of researchers at the Morgridge Institute for Research recently illustrated.