(Press-News.org) A new study in people undergoing surgery to treat seizures related to epilepsy shows that pauses in speech reveal information about how people’s brains plan and produce speech.

Led by researchers at NYU Grossman School of Medicine, the study results add to evidence that neighboring brain regions, the inferior frontal gyrus and the motor cortex, play an important role in such planning before words are said aloud. Both are part of the folded top layers of the brain, or cerebral cortex, which has long been known to control the muscle (motor) movements in the throat and mouth needed to produce speech. Less clear until now was how closely these regions determine the mix of sounds and words people want to say aloud, the authors report.

Publishing in the journal Brain online March 19, the findings come from an analysis of hundreds of brain-mapping recordings made on 16 patients between the ages of 14 and 43 preparing for surgery to treat epilepsy at NYU Langone Health between 2018 and 2021.

As a routine part of their procedures, surgeons electrically (and painlessly) stimulate specific parts of the brain while asking patients to perform standardized speaking tasks. Patients are asked, for example, to recite numbers or days of the week, or even the Pledge of Allegiance. The goal before surgery, researchers say, is to isolate and spare the parts of the brain nearby needed for speech, as marked by increased slurring or total loss of speech following electrical stimulation. This enables surgeons to remove only the brain tissue responsible for the errant electrical signals that cause seizures.

What makes the new study unique, the researchers say, was their measurement and analysis of the time intervals, lasting less than two seconds, during which brain stimulation starts and speech becomes slurred and eventually stops. Previous research, they note, did not directly measure such latencies, but instead relied on behavioral observations to inform which brain regions were involved in whether a patient could continue to speak or not after stimulation of the cortex.

Measuring the latencies, they say, provides new insight into the parts of the cortex involved in planning speech, even if not responsible for actually voicing and mouthing the words. Among the new study findings was that latencies between electrical stimulation and eventual loss of the ability to speak were different among brain regions.

Latencies were longest in the inferior or lower regions of the motor cortex as well as another surface layer, the inferior frontal gyrus, at 1.0 second and 0.75 second, respectively. Because patients were able to keep speaking so long after stimulation, investigators say this suggests that these regions are more likely than other regions to be involved in planning what people want to say.

Smaller latencies, lasting on average 0.5 second, were found in other parts of the motor cortex. Researchers say these shorter interruptions of speech indicate that these regions play a more crucial role in the physical mechanics of speaking.

Based on these observations, researchers determined that a pattern of longer latencies corresponded to speech planning in different regions of the brain cortex more likely than shorter latencies, which corresponded to parts of the brain cortex involved in speech production.

“Our study adds evidence for the role of the brain’s motor cortex and inferior frontal gyrus in planning speech and determining what people are preparing to say, not just voicing words using the vocal cords or mouthing the words by moving the tongue and lips,” said study lead investigator Heather Kabakoff, PhD, a speech pathologist at NYU Langone.

“Our results show that mapping out the millisecond time intervals, or latencies, between electrical stimulation in parts of the brain to the disruption or slurring of words and eventual inability to speak can be used to better understand how the human brain works and the roles played by different brain regions in human speech,” said study senior investigator and neuroscientist Adeen Flinker, PhD. “When it comes to mapping out functions of the brain cortex involved in speech, timing is key.”

Flinker, an associate professor in the Department of Neurology at NYU Langone, says the team’s overall findings also confirm that motor execution and speech planning occur in distinctly different areas of the brain.

Clinically, Flinker says the team findings, if further research confirms their work, could help surgeons better refine their brain mapping to protect patients’ speech.

Researchers say their next steps are to evaluate latency patterns in other parts of the brain to determine if they too play a role in the finer functions of planning speech or physically making sounds and words. Tasks include the naming of pictures aloud to determine if poststimulation latencies help distinguish parts of the brain needed to interpret visual inputs and process them into actual words.

They also want to investigate whether latency patterns can expose real-time speech feedback mechanisms by measuring how long it takes patients to correct forced errors. This, they say, could provide insight into how people use the sound of their own voice to control the way they sound.

Funding support for this research was provided by National Institutes of Health grants R01DC018805, R01NS109367, R01NS115929, and F32DC021094.

Besides Flinker and Kabakoff, other NYU Langone researchers involved in the study are co-investigators Leyao Yu, BA; Daniel Friedman, MD; Patricia Dugan, MD; Werner Doyle, MD; and Orrin Devinsky, MD.

Media Inquiries:

David March

212-404-3528

david.march@nyulangone.org

STUDY LINK

https://doi.org/10.1093/braincomms/fcae053

STUDY DOI

10.1093/braincomms/fcae053

IMAGE ALSO AVAILABLE UPON REQUEST

CAPTION

Brain recordings in patients before surgery, as shown during electrical stimulation (as illustrated by sparks), reveal how neighboring regions, the inferior frontal gyrus (shaded center left) and the motor cortex (shaded center right), play a role in how people’s brains plan and produce speech

COURTESY CREDIT

Adeen Flinker at NYU Langone Health/NYU Grossman School of Medicine

END

Brain recordings in people before surgery reveal how all minds plan what to say prior to speaking

2024-03-19

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

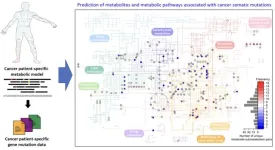

A KAIST-Seoul National University Hospital research team develops a computational workflow that predicts metabolites and metabolic pathways associated with somatic mutations in cancers

2024-03-19

Cancer is characterized by abnormal metabolic processes different from those of normal cells. Therefore, cancer metabolism has been extensively studied to develop effective diagnosis and treatment strategies. Notable achievements of cancer metabolism studies include the discovery of oncometabolites* and the approval of anticancer drugs by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) that target enzymes associated with oncometabolites. Approved anticancer drugs such as ‘Tibsovo (active ingredient: ivosidenib)’ and ‘Idhifa (active ingredient: enasidenib)’ ...

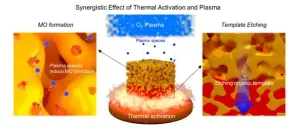

Bendable energy storage materials by cool science

2024-03-19

Imaging being able to wear your smartphone on your wrist, not as a watch, but literally as a flexible band that surrounds around your arm. How about clothes that charge your gadgets just by wearing them? Recently, a collaborative team led by Professor Jin Kon Kim and Dr. Keon-Woo Kim of Pohang University of Science and Technology (POSTECH), Professor Taesung Kim and M.S./Ph.D. student Hyunho Seok of Sungkyunkwan University (SKKU), and Professor Hong Chul Moon of University of Seoul (UOS) has brought a step closer to making this realty. This research work was published in Advanced Materials.

Mesoporous ...

Inorganic nitrate can help protect patients against kidney damage caused during coronary angiographic procedures

2024-03-19

A five-day course of once-daily inorganic nitrate reduces the risk of a serious complication following a coronary angiogram, in which the dye used causes damage to the kidneys. The clinical trial, led by Queen Mary University of London and funded by Heart Research UK, also showed that the five-day course improves renal outcomes at three months and major adverse cardiac events (MACE) at one year compared to placebo.

Contrast-induced nephropathy (CIN), also known as contrast associated acute kidney injury (CA-AKI), is an uncommon but serious complication following ...

Active social lives help dementia patients, caregivers thrive

2024-03-19

EMBARGOED FOR RELEASE

6 p.m. PT / 9 p.m. ET, March 18, 2024

To coincide with publication in The Gerontologist

Media Contact: Suzanne Leigh (415) 680-5133

Suzanne.Leigh@UCSF.edu

Subscribe to UCSF News

People with dementia and those who care for them should be screened for loneliness, so providers can find ways to keep them socially connected, according to experts at UC San Francisco and Harvard, who made the recommendations after finding that both groups experienced declines in social well-being as the disease progressed.

The patients, whose ...

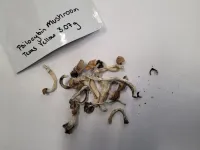

New technique measures psilocybin potency of mushrooms

2024-03-19

Since the 1970s, the federal government has listed the active ingredients in mushrooms—psilocybin and psilocin—as illegal and having no accepted medical use.

However, in recent years, medical professionals have found that these substances are safe and effective for treating stubborn conditions such as treatment-resistant depression and post-traumatic stress disorder. Some jurisdictions now allow for the medical use of mushrooms, while others are considering permitting or at least decriminalizing their recreational use.

Clinicians now find themselves needing to carefully ...

UC Irvine-led research team discovers role of key enzymes that drive cancer mutations

2024-03-19

Irvine, Calif., March 18, 2024 — A research team led by the University of California, Irvine has discovered the key role that the APOBEC3A and APOBEC3B enzymes play in driving cancer mutations by modifying the DNA in tumor genomes, offering potential new targets for intervention strategies.

The study, published today online in the journal Nature Communications, describes how the researchers identified the process by which APOBEC3A and APOBEC3B detect specific DNA structures, resulting in mutations at distinct positions within the tumor genome.

“It’s critical to understand how cancer cells accumulate mutations leading to ...

All creatures great and small: Sequencing the blue whale and Etruscan shrew genomes

2024-03-18

The blue whale genome was published in the journal Molecular Biology and Evolution, and the Etruscan shrew genome was published in the journal Scientific Data.

Research models using animal cell cultures can help navigate big biological questions, but these tools are only useful when following the right map.

“The genome is a blueprint of an organism,” says Yury Bukhman, first author of the published research and a computational biologist in the Ron Stewart Computational Group at the Morgridge Institute, an independent research organization that works in affiliation with the University of Wisconsin–Madison in emerging fields ...

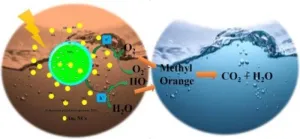

Sustainable solution for wastewater polluted by dyes used in many industries

2024-03-18

Water pollution from dyes used in textile, food, cosmetic and other manufacturing is a major ecological concern with industry and scientists seeking biocompatible and more sustainable alternatives to protect the environment.

A new study led by Flinders University has discovered a novel way to degrade and potentially remove toxic organic chemicals including azo dyes from wastewater, using a chemical photocatalysis process powered by ultraviolet light.

Professor Gunther Andersson, from the Flinders Institute for NanoScale Science and Technology, says the process involves creating metallic ‘clusters’ of just nine gold (Au) atoms chemically ‘anchored’ ...

Food companies’ sponsorship of children’s sports encourages children to buy their products, Canadian research suggests

2024-03-18

*This is an early press release from the European Congress on Obesity (ECO 2024) Venice 12-15 May. Please credit the Congress if using this material*

Food companies’ sponsorship of children’s sports may encourage children to buy their products, new research to be presented at the European Congress on Obesity (ECO 2024) (Venice 12-15 May), has found.

The Canadian research also found that many children view food companies that sponsor or give money to children’s sports as being “generous” ...

USC receives $3.95 million CIRM grant for organoid resource center

2024-03-18

To democratize access to lab-grown organ-like structures known as organoids and other advanced stem cell and transcriptomic technologies, USC will launch the CIRM ASCEND Center, dedicated to “Advancing Stem Cell Education and Novel Discoveries.” Funded by a $3.95 million grant from the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine (CIRM), the voter-created state agency charged with distributing public funding to support stem cell research and education, ASCEND joins a network of shared resources laboratories ...