(Press-News.org) To study how parasites evolve to break the defenses of their hosts, the National Institutes of Health has granted UC Riverside nematologist Simon “Niels” Groen a $1.9 million Outstanding Investigator Award.

Roundworm parasites infect humans, livestock, and crop plants. Insights into why certain worms can evade host immune protections could help preempt a ticking time bomb: the decreasing effectiveness of pesticides and antibiotics for infections.

Bacterial, fungal, and parasite resistance to drugs and pesticides is making it harder, and sometimes impossible, to treat common infections like pneumonia and tuberculosis in humans and pest infestations in crops. International health officials warn that without urgent action, we are heading toward a future in which minor injuries and infections can kill. Crop and livestock production will also face increasing hurdles.

“When roundworms infect either humans, animals or plants, they start injecting proteins from their saliva into host cells to subvert the immune response,” Groen said. “These processes are pretty similar across hosts, which is why we can study coevolutionary arms races between plants and parasitic worms and make inferences about the evolution of worm infections in people.”

Over the next five years, Groen will use the funds to conduct a study in two parts. The first part of the project will examine hundreds of tomato and rice plants, both those grown on farms and those growing in the wild. These are not plants artificially bred for immunity, but Groen expects many will have developed defenses against infectious roundworms, also called nematodes.

“These plants are a natural laboratory in which we can link their genes and chemical characteristics of their roots to their resistance to worm infections,” Groen said.

“We will learn the molecular mechanisms by which plants defend themselves. This includes the production of defensive chemicals, some of which could be harnessed as novel drugs or antibiotics in humans and livestock,” Groen said. “We can then share this information with biomedical researchers and crop breeders.”

This aspect of the project will also help increase food security, particularly in parts of Africa and Asia where nematodes pose a problem for farmers. Much research has been done on above-ground insect pests, but less work has been done below ground, where nematode infections attack the most economically important crops.

“Nematodes make up the most devastating threat to soybeans. For rice and tomatoes, nematodes may cause up to 20% loss of yield. That’s a lot of people who don’t get to eat,” Groen said.

For the second part of the project, the research team will look at the nematode side of the equation. “How do they evolve to break the plants’ resistance?” Groen asked.

There is a gene in tomatoes, Mi-1, that surveys the inside of plant cells for incoming attacks. In a way that is not yet fully understood, this gene perceives something about impending nematode infections that triggers an effective immune response.

Mi-1 was discovered in wild tomatoes in the 1940s and has been bred into California processing tomatoes ever since to keep nematodes at bay. Groen explained that this breeding scheme put root-knot nematodes under enormous natural selection pressure to overcome the resistance conferred by the gene.

However, in increasing numbers, farmers are now finding nematodes in their supposedly resistant tomato crops. “We don’t understand how they broke the resistance. Is there one way, or multiple ways they were able to do this? We will try to identify how many ways there are to skin a cat, from a nematode’s perspective,” Groen said.

Thanks to UC Extension specialists, Groen’s team will be able to compare the genes of worms collected before resistance breaking became more common, as well as ones that have been able to squirm past the plant’s immunity barriers.

One hypothesis is that when the nematode enters the plant, it injects proteins with its saliva that have different targets in the host cell. When Mi-1, floating around in the cell, comes across one of these nematode proteins, it triggers an immune response that kills the worm. However, if the worm no longer injects that protein, then Mi-1 doesn’t know the invader has arrived.

There are receptor proteins like Mi-1 that have evolved similarly in humans that survey cells for incoming attacks, as well as additional molecular processes that resemble one another in humans and plants. However, given ethical and logistical considerations with studying infections in humans, it makes sense to begin this research with plants and nematodes.

“The worms are only one model system to look at resistance breaking. But they may yet help us find new solutions to pesticide and antibiotic resistance,” Groen said.

END

Solving antibiotic and pesticide resistance with infectious worms

UCR scientist wins $1.9 million to decode nematodes’ attack strategies

2024-04-18

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Three ORNL scientists elected AAAS Fellows

2024-04-18

Three scientists from the Department of Energy’s Oak Ridge National Laboratory have been elected fellows of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, or AAAS, the world’s largest general scientific society and publisher of the Science family of journals.

"Keith Kline, Rigoberto Advincula and Takeshi Egami have delivered significant impact for the scientific community," said ORNL Director Stephen Streiffer. "This distinguished honor highlights their commitment, hard work and leadership in their respective fields. I offer my congratulations to them on this well-deserved recognition.”

AAAS ...

Rice bioengineers win $1.4 million ARPA-H grant for osteoarthritis research

2024-04-18

HOUSTON – (April 18, 2024) – Bioengineers at Rice University have been awarded $1.4 million as part of a multi-center consortium funded by the Advanced Research Projects Agency for Health (ARPA-H) to develop strategies for reversing the effects of osteoarthritis.

“We’re thrilled to be a part of this collaborative effort to tackle one of the most challenging degenerative joint diseases and develop, test and commercialize solutions for patients,” said Antonios Mikos, the Louis Calder Professor of Chemical Engineering and professor of bioengineering ...

COVID-19 booster immunity lasts much longer than primary series alone, York University-led study shows

2024-04-18

April 18, 2024, TORONTO – Thinking about getting a spring-time booster shot? A new study coming out of York University’s Centre for Disease Modelling in the Faculty of Science shows that immunity after a COVID-19 booster lasts much longer than the primary series alone. These findings are among other, sometimes “unintuitive,” revelations of how factors like age, sex and comorbidities do and don’t affect immune response.

The study’s authors – York Post Doctoral researchers Chapin ...

Bentham Science joins United2Act

2024-04-18

Bentham Science Publishers is now a signatory organization of United2Act's consensus statement on paper mills.

We are committed to upholding the highest standards of research integrity in academic and scientific publishing. Part of the effort to uphold integrity in scientific publishing includes preventing publication from fraudulent 'paper mills' which negatively impact the credibility of research. We fully support the COPE position statement on this critical issue.

The intrusion of fraudulent papers into the publication record not only undermines public trust in research but also poses significant risks to ...

When thoughts flow in one direction

2024-04-18

Contrary to previous assumptions, nerve cells in the human neocortex are wired differently than in mice. Those are the findings of a new study conducted by Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin and published in the journal Science.* The study found that human neurons communicate in one direction, while in mice, signals tend to flow in loops. This increases the efficiency and capacity of the human brain to process information. These discoveries could further the development of artificial neural networks.

The neocortex, a critical structure for human intelligence, is less than five millimeters thick. There, in the outermost layer of the brain, 20 billion neurons process ...

Scientists identify airway cells that sense aspirated water and acid reflux

2024-04-18

Scientists Identify Airway Cells That Sense Aspirated Water and Acid Reflux

The new work by UCSF researchers could lead to interventions to prevent pneumonia or treat certain types of chronic cough.

When a mouthful of water goes down the wrong pipe – heading toward a healthy person’s lungs instead of their gut – they start coughing uncontrollably. That’s because their upper airway senses the water and quickly signals the brain. The same coughing reflex is set off in people with acid reflux, when acid from the stomach reaches the throat.

Now, UC San Francisco scientists have identified the rare type of cell responsible ...

China’s major cities show considerable subsidence from human activities

2024-04-18

The land under nearly half of China’s major cities is undergoing moderate to severe subsidence, affecting roughly one-third of the nation’s urban population, according to a systematic national-scale satellite assessment. The findings suggest that within the next century, 22 to 26% of China’s coastal land will have a relative elevation lower than sea level, putting hundreds of millions of people at elevated risk of flooding due to sea-level rise. Over the last several decades, China has experienced one of the most rapid and extensive urban expansions in human history. This massive wave of urbanization may be threatened ...

Drugs of abuse alter neuronal signaling to reprioritize use over innate needs

2024-04-18

Drugs of abuse, like cocaine and opioids, alter neuronal signaling in the nucleus accumbens (NAc), hijacking a key brain reward system involved with the fulfillment of innate needs for survival, according to a new study in mice. The findings provide mechanistic insights into the intensification of drug-seeking behaviors in substance use disorders. Persistent drug use is accompanied by a profound reprioritization of motivations, skewing decision-making behaviors toward a myopic focus on drug use over other innate needs, like eating or drinking water, often ...

Mess is best: disordered structure of battery-like devices improves performance

2024-04-18

The energy density of supercapacitors – battery-like devices that can charge in seconds or a few minutes – can be improved by increasing the ‘messiness’ of their internal structure.

Researchers led by the University of Cambridge used experimental and computer modelling techniques to study the porous carbon electrodes used in supercapacitors. They found that electrodes with a more disordered chemical structure stored far more energy than electrodes with a highly ordered structure.

Supercapacitors are a key technology for the energy transition and could be useful for certain forms of public transport, as well as for ...

Skyrmions move at record speeds: a step towards the computing of the future

2024-04-18

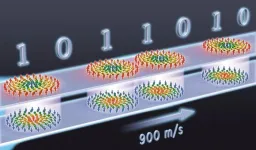

An international research team led by scientists from the CNRS1 has discovered that the magnetic nanobubbles2 known as skyrmions can be moved by electrical currents, attaining record speeds up to 900 m/s.

Anticipated as future bits in computer memory, these nanobubbles offer enhanced avenues for information processing in electronic devices. Their tiny size3 provides great computing and information storage capacity, as well as low energy consumption.

Until now, these nanobubbles moved no faster than 100 m/s, which is too slow for computing applications. ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Roadmap for Europe’s biodiversity monitoring system

Novel camel antimicrobial peptides show promise against drug-resistant bacteria

Scientists discover why we know when to stop scratching an itch

A hidden reason inner ear cells die – and what it means for preventing hearing loss

Researchers discover how tuberculosis bacteria use a “stealth” mechanism to evade the immune system

New microscopy technique lets scientists see cells in unprecedented detail and color

Sometimes less is more: Scientists rethink how to pack medicine into tiny delivery capsules

Scientists build low-cost microscope to study living cells in zero gravity

The Biophysical Journal names Denis V. Titov the 2025 Paper of the Year-Early Career Investigator awardee

Scientists show how your body senses cold—and why menthol feels cool

Scientists deliver new molecule for getting DNA into cells

Study reveals insights about brain regions linked to OCD, informing potential treatments

Does ocean saltiness influence El Niño?

2026 Young Investigators: ONR celebrates new talent tackling warfighter challenges

Genetics help explain who gets the ‘telltale tingle’ from music, art and literature

Many Americans misunderstand medical aid in dying laws

Researchers publish landmark infectious disease study in ‘Science’

New NSF award supports innovative role-playing game approach to strengthening research security in academia

Kumar named to ACMA Emerging Leaders Program for 2026

AI language models could transform aquatic environmental risk assessment

New isotope tools reveal hidden pathways reshaping the global nitrogen cycle

Study reveals how antibiotic structure controls removal from water using biochar

Why chronic pain lasts longer in women: Immune cells offer clues

Toxic exposure creates epigenetic disease risk over 20 generations

More time spent on social media linked to steroid use intentions among boys and men

New study suggests a “kick it while it’s down” approach to cancer treatment could improve cure rates

Milken Institute, Ann Theodore Foundation launch new grant to support clinical trial for potential sarcoidosis treatment

New strategies boost effectiveness of CAR-NK therapy against cancer

Study: Adolescent cannabis use linked to doubling risk of psychotic and bipolar disorders

Invisible harms: drug-related deaths spike after hurricanes and tropical storms

[Press-News.org] Solving antibiotic and pesticide resistance with infectious wormsUCR scientist wins $1.9 million to decode nematodes’ attack strategies