(Press-News.org) Philadelphia, April 24, 2024 – As patients with congenital heart diseases live longer, researchers are attempting to understand some of the other complications they may face as they age. In a new study, a team from Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) used state-of-the-art technologies to understand the underlying biology of Fontan-associated liver disease (FALD).

The findings, published today in Science Translational Medicine, reveal unprecedented insights into how the disease develops and potential therapeutic targets for future treatment options.

The Fontan operation is the current standard of care for single-ventricle congenital heart disease. In this surgery, blood carried by the inferior vena cava, a vein that carries deoxygenated blood from the lower body into the heart, is channeled directly into the pulmonary arteries. After this operation, all the deoxygenated blood from the body is delivered to the lungs but without the benefit of a pump, resulting in the potential for venous congestion. Approximately 80,000 people worldwide have had a Fontan procedure.

The Fontan circulation (FC) – when the heart receives oxygenated blood from the lungs and pumps it to the body – is life-sustaining for individuals with single ventricle type of congenital heart disease but comes with many potential challenges. Patients with FC can face potentially life-threatening complications from early-onset hepatic fibrosis, now known as FALD. As more patients undergo the Fontan surgery for single-ventricle congenital heart disease, FALD has become a more recognized problem. Little information exists on FALD, yet it is distinct from other forms of liver disease, which is why researchers at CHOP wanted to understand the basic biology that could lead to better treatment options and improve these patients’ quality of life.

“As our expertise with Fontan surgery improves and the number of survivors increase, we want to be able to offer these patients an improved quality and duration of life,” said study co-author Jack Rychik, MD, Director of the Fontan Rehabilitation, Wellness, Activity and Resilience Development (FORWARD) Program at CHOP, one of the first multidisciplinary clinics established in the world focused on Fontan circulation specific care. “This study allowed us to achieve a deeper understanding of Fontan-associated liver disease, and this translational research is something we hope leads us to studies that cure and improve the outcomes for patients born with half a heart.”

In the study, researchers generated the first complete atlas of RNA and epigenetic statuses of human FALD at a single-cell level by studying tissues samples from patients with early-stage disease. The atlas revealed profound cell-type specific changes in livers with Fontan circulation. The most significant changes were observed in central hepatocytes, cells that play a key role in proper liver function. The researchers found that these hepatocytes had significant metabolic reprograming that preceded the activation of other cells closely associated with FALD, suggesting that central hepatocytes are a key part in understanding the origins of the disease.

The researchers also identified how Activins A and B, signaling molecules involved in several key developmental processes, may play a role in the development of fibrosis, or the thickening or scarring of tissue that in this case can contribute to FALD, suggesting that they may serve as potential therapeutic targets.

“Our findings make the case that there may be some way for us to blunt the process that leads to scarring at the cellular level,” said senior study author Liming Pei, PhD, an associate professor of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine at CHOP and member of the CHOP Cardiovascular Institute. “The pathways we identified are worth studying in additional models and confirming whether that information could lead to the discovery of new therapeutic options.”

This study was supported by the Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health Affairs through the Peer Reviewed Medical Research Program under Awards W81XWH20-1-0042, W81XWH20-1-0089, W81XWH22-1-0058 and W81XWH22-1-0561, NIH R01DK111495, U54HL165442, U01HL166058, P30DK019525, the American Heart Association Established Investigator Award 227477, a CHOP Foerderer Award, an SVRF grant from Additional Ventures, and by the Robert & Dolores Harrington Endowed Chair in Cardiology at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

Hu et al, “Single-cell multiomics guided mechanistic understanding of Fontan-associated liver disease.” Sci Transl Med. Online April 24, 2024. DOI: 10.1126/scitranslmed.adk6213.

About Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia:

A non-profit, charitable organization, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia was founded in 1855 as the nation’s first pediatric hospital. Through its long-standing commitment to providing exceptional patient care, training new generations of pediatric healthcare professionals, and pioneering major research initiatives, the hospital has fostered many discoveries that have benefited children worldwide. Its pediatric research program is among the largest in the country. The institution has a well-established history of providing advanced pediatric care close to home through its CHOP Care Network, which includes more than 50 primary care practices, specialty care and surgical centers, urgent care centers, and community hospital alliances throughout Pennsylvania and New Jersey, as well as the Middleman Family Pavilion and its dedicated pediatric emergency department in King of Prussia. In addition, its unique family-centered care and public service programs have brought Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia recognition as a leading advocate for children and adolescents. For more information, visit https://www.chop.edu.

END

CHOP researchers discover underlying biology behind Fontan-associated liver disease

Findings provide some of the first evidence of potential therapeutic targets for condition affecting thousands of patients with single ventricle congenital heart disease

2024-04-24

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

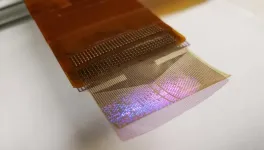

A flexible microdisplay can monitor brain activity in real-time during brain surgery

2024-04-24

A thin film that combines an electrode grid and LEDs can both track and produce a visual representation of the brain’s activity in real-time during surgery–a huge improvement over the current state of the art. The device is designed to provide neurosurgeons visual information about a patient’s brain to monitor brain states during surgical interventions to remove brain lesions including tumors and epileptic tissue.

Each LED in the device mirrors the activity of a few thousand neurons. In a series of proof-of-concept experiments in rodents and large non-primate mammals, researchers showed that ...

Diversity and productivity go branch-in-branch

2024-04-24

Kyoto, Japan -- Climate change can be characterized as the Grim Reaper or some other harbinger of dire times for humanity and natural environment, including forests. Previous studies reporting a decline in forest productivity due to climate warming and long-term drought may suggest that trees' survival hangs in the balance.

Now, a study by an international group, including Kyoto University, found that forests with higher trait diversity not only adapt better to climate change but may also thrive.

The study, conducted by researchers from Lakehead ...

Color variants in cuckoos: the advantages of rareness

2024-04-24

Every cuckoo is an adopted child – raised by foster parents, into whose nest the cuckoo mother smuggled her egg. The cuckoo mother is aided in this subterfuge by her resemblance to a bird of prey. There are two variants of female cuckoos: a gray morph that looks like a sparrowhawk, and a rufous morph. Male cuckoos are always gray.

“With this mimicry, the bird imitates dangerous predators of the host birds, so that they keep their distance instead of attacking,” says Professor Jochen Wolf from LMU Munich. Together with researchers at CIBIO (Centro de Investigação ...

Laser technology offers breakthrough in detecting illegal ivory

2024-04-24

A new way of quickly distinguishing between illegal elephant ivory and legal mammoth tusk ivory could prove critical to fighting the illegal ivory trade. A laser-based approach developed by scientists at the Universities of Bristol and Lancaster, could be used by customs worldwide to aid in the enforcement of illegal ivory from being traded under the guise of legal ivory. Results from the study are published in PLOS ONE today [24 April].

Despite the Convention on the International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) ban on ivory, poaching associated with its illegal trade has ...

Why can’t robots outrun animals?

2024-04-24

Robotics engineers have worked for decades and invested many millions of research dollars in attempts to create a robot that can walk or run as well as an animal. And yet, it remains the case that many animals are capable of feats that would be impossible for robots that exist today.

“A wildebeest can migrate for thousands of kilometres over rough terrain, a mountain goat can climb up a literal cliff, finding footholds that don't even seem to be there, and cockroaches can lose a leg and not slow down,” ...

After spinal cord injury, neurons wreak havoc on metabolism

2024-04-24

COLUMBUS, Ohio – Conditions such as diabetes, heart attack and vascular diseases commonly diagnosed in people with spinal cord injuries can be traced to abnormal post-injury neuronal activity that causes abdominal fat tissue compounds to leak and pool in the liver and other organs, a new animal study has found.

After discovering the connection between dysregulated neuron function and the breakdown of triglycerides in fat tissue in mice, researchers found that a short course of the drug gabapentin, commonly prescribed for nerve pain, prevented ...

Network model unifies recency and central tendency biases

2024-04-24

Neuroscientists have revealed that recency bias in working memory naturally leads to central tendency bias, the phenomenon where people’s (and animals’) judgements are biased towards the average of previous observations. Their findings may hint at why the phenomenon is so ubiquitous.

Researchers in the Akrami Lab at the Sainsbury Wellcome Centre at UCL and the Clopath Lab at Imperial College London developed a network model with a working memory module and another accounting for sensory histories. The study, published in eLife, describes how the model shows neural circuits ...

Ludwig Lausanne scientists identify and show how to target a key tumor defense against immune attack

2024-04-24

April 24, 2024, NEW YORK – A Ludwig Cancer Research study has discovered how a lipid molecule found at high levels within tumors undermines the anti-cancer immune response and compromises a recently approved immunotherapy known as adoptive cell therapy (ACT) using tumor infiltrating lymphocytes, or TIL-ACT. In this individualized cell therapy, TILs—CD8+ T cells that kill cancer cells—are expanded in culture from a patient’s tumor samples and reinfused into the patient as a treatment.

Researchers led by Ludwig Lausanne’s Matteo ...

Can climate change accelerate transmission of malaria? Pioneering research sheds light on impacts of temperature

2024-04-24

In 2022, an estimated 249 million malaria cases killed 608,000 people in 85 countries worldwide including the United States, according to the World Health Organization.

Malaria continues to pose a considerable public health risk in tropical and subtropical areas, where it impacts human health and economic progress.

Despite concerns about the potential impact of climate change on increasing malaria risk, there is still limited understanding of how temperature affects malaria transmission – until now.

Malaria is a mosquito-borne disease caused by a parasite that spreads from bites of infected female Anopheles mosquitoes. If left untreated in humans, malaria can cause severe symptoms, ...

A new attempt to identify salt gland development and salt resistance genes of Limonium bicolor ——Identification of bHLH gene family and its function analysis in salt gland development

2024-04-24

The secondary salinization of saline-alkali land is increasing globally. It is of strategic significance to explore the salt-tolerant molecular mechanism of halophytes and cultivate saline-alkali resistant crops for the improvement of saline-alkali land. The recretohalophyte Limonium bicolor has a unique salt-secreting structure, salt gland, which can directly excrete Na+ out of the body to effectively avoid salt stress. Exploring the development mechanism of salt gland structure in recretohalophyte is of great significance for analyzing the development of plant epidermis structure and improving the salt-resistant mechanism of plants.

Recently, Wang ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Mining the dark transcriptome: University of Toronto Engineering researchers create the first potential drug molecules from long noncoding RNA

IU researchers identify clotting protein as potential target in pancreatic cancer

Human moral agency irreplaceable in the era of artificial intelligence

Racial, political cues on social media shape TV audiences’ choices

New model offers ‘clear path’ to keeping clean water flowing in rural Africa

Ochsner MD Anderson to be first in the southern U.S. to offer precision cancer radiation treatment

Newly transferred jumping genes drive lethal mutations

Where wells run deep, biodiversity runs thin

Q&A: Gassing up bioengineered materials for wound healing

From genetics to AI: Integrated approaches to decoding human language in the brain

Leora Westbrook appointed executive director of NR2F1 Foundation

Massive-scale spatial multiplexing with 3D-printed photonic lanterns achieved by researchers

Younger stroke survivors face greater concentration, mental health challenges — especially those not employed

From chatbots to assembly lines: the impact of AI on workplace safety

Low testosterone levels may be associated with increased risk of prostate cancer progression during surveillance

Analysis of ancient parrot DNA reveals sophisticated, long-distance animal trade network that pre-dates the Inca Empire

How does snow gather on a roof?

Modeling how pollen flows through urban areas

Blood test predicts dementia in women as many as 25 years before symptoms begin

Female reproductive cancers and the sex gap in survival

GLP-1RA switching and treatment persistence in adults without diabetes

Gnaw-y by nature: Researchers discover neural circuit that rewards gnawing behavior in rodents

Research alert: How one receptor can help — or hurt — your blood vessels

Lamprey-inspired amphibious suction disc with hybrid adhesion mechanism

A domain generalization method for EEG based on domain-invariant feature and data augmentation

Bionic wearable ECG with multimodal large language models: coherent temporal modeling for early ischemia warning and reperfusion risk stratification

JMIR Publications partners with the University of Turku for unlimited OA publishing

Strange cosmic burst from colliding galaxies shines light on heavy elements

Press program now available for the world's largest physics meeting

New release: Wiley’s Mass Spectra of Designer Drugs 2026 expands coverage of emerging novel psychoactive substances

[Press-News.org] CHOP researchers discover underlying biology behind Fontan-associated liver diseaseFindings provide some of the first evidence of potential therapeutic targets for condition affecting thousands of patients with single ventricle congenital heart disease