(Press-News.org) Discrimination may speed up the biological processes of aging, according to a new study led by researchers at the NYU School of Global Public Health.

The research links interpersonal discrimination to changes at the molecular level, revealing a potential root cause of disparities in aging-related illness and death.

“Experiencing discrimination appears to hasten the process of aging, which may be contributing to disease and early mortality and fueling health disparities,” said Adolfo Cuevas, assistant professor in the Department of Social and Behavioral Sciences at NYU’s School of Global Public Health and senior author of the study published in the journal Brain, Behavior, and Immunity-Health.

Research shows that people who experience discrimination based on their identity (e.g. race, gender, weight, or disability) are at increased risk for a range of health issues, including heart disease, high blood pressure, and depression. While the precise biological factors driving these poor health outcomes are not fully understood, chronic activation of the body’s stress response is a likely contributor. Moreover, a growing body of research connects persistent exposure to discrimination to the biological processes of aging.

To better understand the connection between discrimination and aging, Cuevas and his colleagues looked at three measures of DNA methylation, a marker that can be used to assess the biological impacts of stress and the aging process. Blood samples and surveys were collected from nearly 2,000 U.S. adults as part of the Midlife in the United States (MIDUS) study, a longitudinal analysis of health and well-being funded by the National Institute on Aging.

Participants were asked about their experiences with three forms of discrimination: everyday, major, and workplace. Everyday discrimination refers to subtle and minor instances of disrespect in daily life, whereas major discrimination focuses on acute and intense instances of discrimination (for example, being physically threatened by police officers). Discrimination in the workplace includes unjust practices, stunted professional opportunities, and punishment based on identity.

The researchers found that discrimination was linked to accelerated biological aging, with people who reported more discrimination aging faster biologically compared to those who experienced less discrimination. Everyday and major discrimination were consistently associated with biological aging, while exposure to discrimination in the workplace was also linked to accelerated aging, but its impact was comparatively less severe.

A deeper analysis showed that two health factors—smoking and body mass index—explained roughly half of the association between discrimination and aging, suggesting that other stress responses to discrimination, such as increased cortisol and poor sleep, are contributing to accelerated aging.

“While health behaviors partly explain these disparities, it’s likely that a range of processes are at play connecting psychosocial stressors to biological aging,” said Cuevas, who is also a core faculty at the Center for Anti-racism, Social Justice, & Public Health at NYU School of Global Public Health.

In addition, the link between discrimination and accelerated biological aging varied by race. Black study participants reported more discrimination and tended to exhibit older biological age and faster biological aging. However, White participants, who reported less discrimination, were more susceptible to the impacts of discrimination when they did experience it, perhaps due to less frequent exposure and fewer coping strategies. (Data on other racial and ethnic groups were not available in the MIDUS study.)

“These findings underscore the importance of addressing all forms of discrimination to support healthy aging and promote health equity,” added Cuevas.

In addition to Cuevas, study authors include Steven W. Cole of the University of California, Los Angeles; Daniel W. Belsky of Columbia University; and Anna-Michelle McSorley, Jasmine M. Shon, and Virginia W. Chang of the NYU School of Global Public Health.

The MIDUS study is supported by the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation Research Network and the National Institute on Aging (P01-AG020166 and U19-AG051426). The study itself was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (R01DK137246 and R01DK137805).

About the NYU School of Global Public Health

At the NYU School of Global Public Health (NYU GPH), we are preparing the next generation of public health pioneers with the critical thinking skills, acumen, and entrepreneurial approaches necessary to reinvent the public health paradigm. Devoted to employing a nontraditional, interdisciplinary model, NYU GPH aims to improve health worldwide through a unique blend of global public health studies, research, and practice. The School is located in the heart of New York City and extends to NYU's global network on six continents. Innovation is at the core of our ambitious approach, thinking and teaching. For more, visit: publichealth.nyu.edu

END

Discrimination may accelerate aging

Signs of biological aging at the molecular level linked to small and large experiences of interpersonal discrimination for Black and white Americans

2024-05-09

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

New machine learning algorithm promises advances in computing

2024-05-09

COLUMBUS, Ohio – Systems controlled by next-generation computing algorithms could give rise to better and more efficient machine learning products, a new study suggests.

Using machine learning tools to create a digital twin, or a virtual copy, of an electronic circuit that exhibits chaotic behavior, researchers found that they were successful at predicting how it would behave and using that information to control it.

Many everyday devices, like thermostats and cruise control, utilize linear controllers – which use ...

How climate change will affect malaria transmission

2024-05-09

University of Leeds news release

Embargoed until 1900 BST, 9 May 2024

How climate change will affect malaria transmission

A new model for predicting the effects of climate change on malaria transmission in Africa could lead to more targeted interventions to control the disease according to a new study.

Previous methods have used rainfall totals to indicate the presence of surface water suitable for breeding mosquitoes, but the research led by the University of Leeds used several climatic and hydrological models to include real-world processes of evaporation, infiltration and flow through rivers.

This ...

Presenting a safer, low-cost, and low-energy whole-body magnetic resonance imaging device

2024-05-09

Machine learning enables cheaper and safer low-power magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) without sacrificing accuracy, according to a new study. According to the authors, these advances pave the way for affordable, patient-centric, and deep learning-powered ultra-low-field (ULF) MRI scanners, addressing unmet clinical needs in diverse healthcare settings worldwide. Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) has revolutionized healthcare, offering noninvasive and radiation-free imaging. It holds immense promise for advancing medical diagnoses through artificial intelligence. However, despite its five decades of development, MRI remains largely inaccessible, particularly ...

Climate models predict larger than expected decline in African malaria transmission areas

2024-05-09

Areas at risk for malaria transmission in Africa may decline more than previously expected because of climate change in the 21st century, suggests an ensemble of environmental and hydrologic models. The combined models predicted that the total area of suitable malaria transmission will start to decline in Africa after 2025 through 2100, including in West Africa and as far east as South Sudan. The new study’s approach captures hydrologic features that are typically missed with standard predictive models of malaria transmission, offering a more nuanced view that could inform malaria control efforts in a warming world. Most of the burden of malaria falls on people living ...

Indian ocean temperature anomalies predict global dengue trends

2024-05-09

Sea surface temperature anomalies in the Indian Ocean predict the magnitude of global dengue epidemics, according to a new study. The findings suggest that the climate indicator could enhance the forecasting and planning for outbreak responses. Dengue – a mosquito-borne flavivirus disease – affects nearly half the world’s population. Currently, there are no specific drugs or vaccines for the disease, and outbreaks can have serious public health and economic impacts. As a result, the ability to predict the risk of outbreaks and prepare accordingly is crucial for many regions where ...

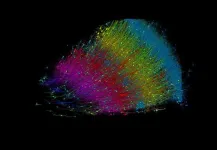

Cubic millimeter fragment of human brain reconstructed at nanoscale resolution

2024-05-09

Using more than 1.4 petabytes of electron microscopy (EM) imaging data, researchers have generated a nanoscale-resolution reconstruction of a millimeter-scale fragment of human cerebral cortex, providing an unprecedented view into the structural organization of brain tissue at the supracellular, cellular, and subcellular levels. The human brain is a vastly complex organ and, to date, little is known about its cellular microstructure, including the synaptic and neural circuits it supports. Disruption of these circuits is known to play a role in myriad brain disorders. Yet studying human brain ...

What makes a public health campaign successful?

2024-05-09

The highest performing countries across public health outcomes share many drivers that contribute to their success. That’s the conclusion of a new study published May 9 in the open-access journal PLOS Global Public Health by Dr. Nadia Akseer, an Epidemiologist-Biostatistician at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and co-author of the study and colleagues in the Exemplars in Global Health (EGH) program.

In recent years, the EGH program has begun to identify and study positive outliers when it comes to global health programs around the world, with an aim of uncovering not only which health interventions work, ...

Manganese sprinkled with iridium: a quantum leap in green hydrogen production

2024-05-09

As the world is transitioning from a fossil fuel-based energy economy, many are betting on hydrogen to become the dominant energy currency. But producing “green” hydrogen without using fossil fuels is not yet possible on the scale we need because it requires iridium, a metal that is extremely rare. In a study published May 10 in Science, researchers led by Ryuhei Nakamura at the RIKEN Center for Sustainable Resource Science (CSRS) in Japan report a new method that reduces the amount of iridium needed for the reaction by 95%, without altering the rate of hydrogen production. This breakthrough could revolutionize our ability to produce ecologically ...

Topological Phonos: Where vibrations find their twist

2024-05-09

An international team of researchers has discovered that the quantum particles responsible for the vibrations of materials—which influence their stability and various other properties—can be classified through topology. Phonons, the collective vibrational modes of atoms within a crystal lattice, generate disturbances that propagate like waves through neighboring atoms. These phonons are vital for many properties of solid-state systems, including thermal and electrical conductivity, neutron scattering, and quantum phases like charge density waves and superconductivity.

The spectrum of phonons—essentially ...

A fragment of human brain, mapped

2024-05-09

A cubic millimeter of brain tissue may not sound like much. But considering that tiny square contains 57,000 cells, 230 millimeters of blood vessels, and 150 million synapses, all amounting to 1,400 terabytes of data, Harvard and Google researchers have just accomplished something enormous.

A Harvard team led by Jeff Lichtman, the Jeremy R. Knowles Professor of Molecular and Cellular Biology and newly appointed dean of science, has co-created with Google researchers the largest synaptic-resolution, 3D reconstruction of a piece of human brain to date, showing in vivid detail each cell and its web of neural connections in a piece of human ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Science reveals why you can’t resist a snack – even when you’re full

Kidney cancer study finds belzutifan plus pembrolizumab post-surgery helps patients at high risk for relapse stay cancer-free longer

Alkali cation effects in electrochemical carbon dioxide reduction

Test platforms for charging wireless cars now fit on a bench

$3 million NIH grant funds national study of Medicare Advantage’s benefit expansion into social supports

Amplified Sciences achieves CAP accreditation for cutting-edge diagnostic lab

Fred Hutch announces 12 recipients of the annual Harold M. Weintraub Graduate Student Award

Native forest litter helps rebuild soil life in post-mining landscapes

Mountain soils in arid regions may emit more greenhouse gas as climate shifts, new study finds

Pairing biochar with other soil amendments could unlock stronger gains in soil health

Why do we get a skip in our step when we’re happy? Thank dopamine

UC Irvine scientists uncover cellular mechanism behind muscle repair

Platform to map living brain noninvasively takes next big step

Stress-testing the Cascadia Subduction Zone reveals variability that could impact how earthquakes spread

We may be underestimating the true carbon cost of northern wildfires

Blood test predicts which bladder cancer patients may safely skip surgery

Kennesaw State's Vijay Anand honored as National Academy of Inventors Senior Member

Recovery from whaling reveals the role of age in Humpback reproduction

Can the canny tick help prevent disease like MS and cancer?

Newcomer children show lower rates of emergency department use for non‑urgent conditions, study finds

Cognitive and neuropsychiatric function in former American football players

From trash to climate tech: rubber gloves find new life as carbon capturers materials

A step towards needed treatments for hantaviruses in new molecular map

Boys are more motivated, while girls are more compassionate?

Study identifies opposing roles for IL6 and IL6R in long-term mortality

AI accurately spots medical disorder from privacy-conscious hand images

Transient Pauli blocking for broadband ultrafast optical switching

Political polarization can spur CO2 emissions, stymie climate action

Researchers develop new strategy for improving inverted perovskite solar cells

Yes! The role of YAP and CTGF as potential therapeutic targets for preventing severe liver disease

[Press-News.org] Discrimination may accelerate agingSigns of biological aging at the molecular level linked to small and large experiences of interpersonal discrimination for Black and white Americans