(Press-News.org) 50,000 years ago, North America was ruled by megafauna. Lumbering mammoths roamed the tundra, while forests were home to towering mastodons, fierce saber-toothed tigers and enormous wolves. Bison and extraordinarily tall camels moved in herds across the continent, while giant beavers plied its lakes and ponds. Immense ground sloths weighing over 1,000 kg were found across many regions east of the Rocky Mountains.

And then, sometime at the end of the Last Ice Age, most of North America’s megafauna disappeared. How and why remains hotly contested. Some researchers believe the arrival of humans was pivotal. Maybe the animals were hunted and eaten, or maybe humans just altered their habitats or competed for vital food sources. But other researchers contend that climate change was to blame, as the Earth thawed after several thousand years of glacial temperatures, changing environments faster than megafauna could adapt. Disagreement between these two schools has been fierce and debates contentious.

Despite decades of study, this Ice Age mystery remains unsolved. We simply don’t have sufficient evidence at this point to rule out one scenario or the other – or indeed other explanations that have been proposed (eg disease, an impact event from a comet, a combination of factors). One of the reasons is that many of the bones through which we track the presence of megafauna are fragmented and difficult to identify. While some sites preserve megafaunal remains really well, conditions at others have been tough on the animal bones, wearing them down into smaller fragments that are too altered to identify. These decay processes include exposure, abrasion, breakage, and biomolecular decay.

Such problems leave us lacking critical information about where particular megafaunal species were distributed, exactly when they disappeared, and how they responded to the arrival of humans or the climatic alteration of environments in the Late Pleistocene.

Applying modern technology to old bones

Our work has set out to address this information deficit. To do so, we have turned our attention to the exceptional collections of the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History in Washington, DC. Housing the findings of numerous archaeological excavations conducted over the past hundred years, the Museum is an extraordinary reservoir of animal bones that are deeply relevant to the question of how North America’s megafauna went extinct. Yet many of these remains are heavily fragmented and unidentifiable, meaning their ability to shed light on this question has, at least up until now, been limited.

Fortunately, recent years have seen the development of new biomolecular methods of archaeological exploration. Rather than heading out to excavate new sites, archaeologists are increasingly turning their attention to the scientific laboratory, using new techniques to probe existing material. One such novel technique is called ZooMS – short for Zooarchaeology by Mass Spectrometry. The method relies on the fact that while most of its proteins degrade quickly after an animal dies, some, like bone collagen, can preserve over long time periods. Since collagen proteins frequently differ in small, subtle ways between different taxonomic groups of animals, and even individual species, collagen sequences can provide a kind of molecular barcode to help identify bone fragments that are otherwise unidentifiable. So, collagen protein segments extracted from minute quantities of bone can be separated and analyzed on a mass spectrometer to perform the identifications of remnant bones that traditional zooarchaeologists cannot.

Selecting archaeological material for study

We decided to use this method to revisit the Smithsonian Museum’s archived material. Our study was a pilot one that asked the key question: would bones housed in the Smithsonian Museum preserve sufficient collagen for us to learn more about fragmented bone material in its storerooms? The answer was not obvious, because many of the excavations had taken place decades ago. While the material had been stored for the last decade or so in a state-of-the-art, climate-controlled facility, the early date of the excavations meant that modern standards were not necessarily applied to their handling, processing, and storage at all stages.

We examined bone material from five archaeological sites. The sites all dated to the Late Pleistocene/earliest Holocene (c. 13,000 to 10,000 calendar years before present) or earlier and were located in Colorado, in the western United States. The earliest had been excavated in 1934, the latest in 1981. Although some of the material from the sites was identifiable, much of it was highly fragmented and did not retain diagnostic features that could enable zooarchaeological identification to species, genus or even family. Some of the bone fragments looked highly unpromising – they were bleached and weathered, or edge-rounded, suggesting they had been transported by water or sediment prior to burial at the site.

Discovering excellent biomolecular preservation

What we found surprised us. Despite the old age of many of the collections, the unpromising appearance of much of the material, and the ancient origins of the bones themselves, they yielded excellent ZooMS results. In fact, a remarkable 80% of the bones sampled yielded sufficient collagen for ZooMS identifications. 73% could be identified to genus level.

The taxa we identified using ZooMS included Bison, Mammuthus (the genus to which mammoths belong), Camelidae (the camel family), and possibly Mammut (the genus to which mastodons belong). In some cases, we could only assign the specimens to broad taxonomic groups because many North American animals still lack ZooMS reference libraries. These databases, which are comparatively well developed for Eurasia but not for other regions, are essential for identifying the spectra a sample produces when we run it on a mass spectrometer.

Our findings have major implications for museum collections. The material we looked at is in every way the poor cousin of the glamorous material that goes on display in natural history museums. To look at, these highly fragmentary, small and undiagnostic animal bones are uninspiring and superficially uninformative. But like other biomolecular tools, ZooMS is revealing the rich information retained in neglected specimens that have drawn neither researcher nor visitor attention for decades.

Our results also highlight the potential of such collections for addressing ongoing debates about exactly when, where and how megafauna went extinct. By opening up for analysis the fragmented bone material that makes up much of the megafaunal record, ZooMS has the potential to help provide much new research data to address long-standing questions about megafaunal extinctions. ZooMS offers a relatively easy, rapid, and cheap way to extract new information from long-ago excavated sites.

Our research also highlights the importance of preserving archaeological collections. When researchers and institutions are strapped for funding, archaeological artefacts and bones that are not glamorous or of obvious immediate benefit may be neglected or even discarded. It is critical that museums are provided with adequate funding to care for and house archaeological remains over the long term. As our analysis shows, such old material can find new life in unexpected ways – in this case, allowing us to use tiny bone fragments to help get a little closer to solving the mystery of why some of Earth’s largest ever animals disappeared from the landscapes of ancient North America.

END

Clues to mysterious disappearance of North America’s large mammals 50,000 years ago found within ancient bone collagen

Dr Mariya Antonosyan, Dr Torben Rick, and Prof Nicole Boivin are co-authors of a new Frontiers in Mammal Science article in which they used new methods to identify fossil bone fragments housed at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History.

2024-05-31

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

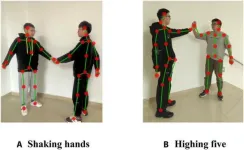

Revolutionizing interaction recognition: The power of merge-and-split graph convolutional networks

2024-05-31

In a significant advancement for robotics and artificial intelligence, researchers at Chongqing University of Technology, along with their international collaborators, have developed a cutting-edge method for enhancing interaction recognition. The study, published in Cyborg and Bionic Systems, introduces the Merge-and-Split Graph Convolutional Network (MS-GCN), a novel approach specifically designed to address the complexities of skeleton-based interaction recognition.

Human interaction recognition plays a crucial role in various applications, ranging from enhancing human-computer interfaces ...

Do shape-memory alloys remember past strains in their life?

2024-05-31

Endowed with the power of memory, certain alloys can magically return to their original shape when heated or deformed. However, the repeated back-and-forth between the original and new configuration may leave permanent imprints on the alloy’s microscopic features, which could then impact its ability to reversibly transform shape. Thus, unraveling the impact of the strain history on these alloys’ functionality is essential to improving predictive capabilities, but it has not received enough attention.

To fill this knowledge gap, the National Science Foundation ...

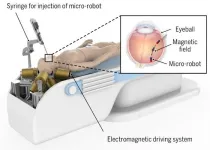

A novel electromagnetic driving system for 5-DOF manipulation in intraocular microsurgery

2024-05-31

The electromagnetic driving systems are proposed for the flexible 5-DOF magnetic manipulation of a micro-robot within the posterior eye, enabling precise targeted drug delivery. A research team has presented a novel electromagnetic driving system that consists of eight optimized electromagnets arranged in an optimal configuration and employs a control framework based on an active disturbance rejection controller (ADRC) and virtual boundary.

The team published their findings in Cyborg and Bionic Systems on Mar 23, 2024.

Intraocular microsurgery has witnessed a transition from the utilization of conventional handheld surgical tools to the adoption of robot-assisted surgery, owing ...

Researchers identify a genetic cause of intellectual disability affecting tens of thousands

2024-05-31

New York, NY [May 31, 2024]—Researchers at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai and others have identified a neurodevelopmental disorder, caused by mutations in a single gene, that affects tens of thousands of people worldwide. The work, published in the May 31 online issue of Nature Medicine [DOI: 10.1038/s41591-024-03085-5], was done in collaboration with colleagues at the University of Bristol, UK; KU Leuven, Belgium; and the NIHR BioResource, currently based at the University of Cambridge, UK.

The findings will improve clinical diagnostic ...

EMBARGOED: Nearly one-third of US adults know someone who’s died of drug overdose

2024-05-31

Losing a loved one to drug overdose has been a common experience for many Americans in recent years, crossing political and socioeconomic divides and boosting the perceived importance of the overdose crisis as a policy issue, according to a new survey led by researchers at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

A nationally representative survey of more than 2,300 Americans, fielded in spring 2023, suggests that 32 percent of the U.S. adult population, or an estimated 82.7 million individuals, has lost someone they know to a fatal drug overdose. ...

Mediterranean diet adherence and risk of all-cause mortality in women

2024-05-31

About The Study: Higher adherence to the Mediterranean diet was associated with a 23% lower risk of all-cause mortality in this cohort study. This inverse association was partially explained by multiple cardiometabolic factors.

Corresponding Author: To contact the corresponding author, Shafqat Ahmad, Ph.D., email shafqat.ahmad@medsci.uu.se.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.14322)

Editor’s Note: Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, author contributions and affiliations, conflict of interest ...

Traumatic brain injury strikes 1 in 8 older Americans

2024-05-31

Some 13% of older adults are diagnosed with traumatic brain injury (TBI), according to a study by UC San Francisco and the San Francisco VA Health Care System. These injuries are typically caused by falls from ground level.

Researchers followed about 9,200 Medicare enrollees, whose average age was 75 at the start of the study, and found that contrary to other studies of younger people, being female, white, healthier and wealthier was associated with higher risk of TBI.

The study publishes in JAMA Network Open on May 31, 2024.

The researchers, ...

Stem cells shed new light on how the human embryo forms

2024-05-31

A new study using stem cell-based models has shed new light on how the human embryo begins to develop, which could one day benefit the development of fertility treatment.

The study led by at the University of Exeter Living Systems Institute has revealed how early embryo cells decide between contributing to the foetus or to the supporting yolk sac.

Understanding this decision is important because the yolk sac is essential for later development in the womb. Producing the right number of yolk sac forming cells may be critical for infertility treatment using in vitro fertilised (IVF) embryos.

Only limited research ...

BU study finds policy makers’ use of in-hospital mortality as a sepsis quality metric may unfairly penalize safety-net hospitals

2024-05-31

EMBARGOED by JAMA Network Open until 11 a.m., ET May 31, 2024

Contact: Maria Ober, mpober@bu.edu

BU Study Finds Policy Makers’ Use of In-Hospital Mortality as a Sepsis Quality Metric May Unfairly Penalize Safety-net Hospitals

(Boston)—Sepsis is a leading cause of death and disability and a key target of state and federal quality measures for hospitals. In-hospital mortality of patients with sepsis is frequently measured for benchmarking, both by researchers and policymakers. For example, in New York, sepsis regulations mandate reporting of risk-adjusted in-hospital mortality, and hospitals with lower or higher than expected in-hospital ...

Mediterranean diet tied to one-fifth lower risk of death in women

2024-05-31

Investigators from Brigham and Women’s Hospital identified and assessed underlying mechanisms that may explain the Mediterranean diet’s 23 percent reduction in all-cause mortality risk for American women

The health benefits of the Mediterranean diet have been reported in multiple studies, but there is limited long-term data of its effects in U.S. women and little understanding about why the diet may reduce risk of death. In a new study that followed more than 25,000 initially healthy U.S. women for up ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Molecular glue discovery: large scale instead of lucky strike

Insulin resistance predictor highlights cancer connection

Explaining next-generation solar cells

Slippery ions create a smoother path to blue energy

Magnetic resonance imaging opens the door to better treatments for underdiagnosed atypical Parkinsonisms

National poll finds gaps in community preparedness for teen cardiac emergencies

One strategy to block both drug-resistant bacteria and influenza: new broad-spectrum infection prevention approach validated

Survey: 3 in 4 skip physical therapy homework, stunting progress

College students who spend hours on social media are more likely to be lonely – national US study

Evidence behind intermittent fasting for weight loss fails to match hype

How AI tools like DeepSeek are transforming emotional and mental health care of Chinese youth

Study finds link between sugary drinks and anxiety in young people

Scientists show how to predict world’s deadly scorpion hotspots

ASU researchers to lead AAAS panel on water insecurity in the United States

ASU professor Anne Stone to present at AAAS Conference in Phoenix on ancient origins of modern disease

Proposals for exploring viruses and skin as the next experimental quantum frontiers share US$30,000 science award

ASU researchers showcase scalable tech solutions for older adults living alone with cognitive decline at AAAS 2026

Scientists identify smooth regional trends in fruit fly survival strategies

Antipathy toward snakes? Your parents likely talked you into that at an early age

Sylvester Cancer Tip Sheet for Feb. 2026

Online exposure to medical misinformation concentrated among older adults

Telehealth improves access to genetic services for adult survivors of childhood cancers

Outdated mortality benchmarks risk missing early signs of famine and delay recognizing mass starvation

Newly discovered bacterium converts carbon dioxide into chemicals using electricity

Flipping and reversing mini-proteins could improve disease treatment

Scientists reveal major hidden source of atmospheric nitrogen pollution in fragile lake basin

Biochar emerges as a powerful tool for soil carbon neutrality and climate mitigation

Tiny cell messengers show big promise for safer protein and gene delivery

AMS releases statement regarding the decision to rescind EPA’s 2009 Endangerment Finding

Parents’ alcohol and drug use influences their children’s consumption, research shows

[Press-News.org] Clues to mysterious disappearance of North America’s large mammals 50,000 years ago found within ancient bone collagenDr Mariya Antonosyan, Dr Torben Rick, and Prof Nicole Boivin are co-authors of a new Frontiers in Mammal Science article in which they used new methods to identify fossil bone fragments housed at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History.