(Press-News.org) Plant cold specialists like the spoonworts have adapted well to the cold climates of the Ice Ages. As cold and warm periods alternated, they developed a number of species that also resulted in a proliferation of the genome. Evolutionary biologists from the universities of Heidelberg, Nottingham, and Prague studied the influence this genome duplication has on the adaptive potential of plants. The results show that polyploids – species with more than two sets of chromosomes – can have an accumulation of structural mutations with signals for a possible local adaptation, enabling them to occupy ecological niches time and time again.

The spoonwort genus of the Brassicaceae family separated from its Mediterranean relatives more than ten million years ago. While their direct descendants specialized in response to drought stress, the spoonworts, or Latin Cochlearia, conquered the cold and Arctic habitats at the beginning of the Ice Age 2.5 million years ago. In their earlier studies, researchers under the direction of Prof. Dr Marcus Koch investigated how the Cochlearia were repeatedly able to adapt to the rapidly alternating cold and warm periods over the last two million years. Among other things, the newly created cold-adapted plants developed separate gene pools that came into contact with one another in the cold regions. The exchange of genes gave rise to populations with multiple sets of chromosomes. With the size of their genome continually reduced, they were then able to occupy cold ecological niches time and time again.

Nonetheless, explains Marcus Koch, only little has been known until now about the genomic mechanisms and potential that enable the plants to adapt to rapid changes in the environment. “This is even more extraordinary since the majority of our most important crops is polyploid and hence has multiple sets of chromosomes. This very fact is the result of strong selection during the cultivation and selection process,” states Prof. Koch, whose “Biodiversity and Plant Systematics” research group is based at the Centre for Organismal Studies of Heidelberg University.

In the current research under the direction of Prof. Dr Levi Yant, a diploid reference genome with two sets of chromosomes of an Alpine spoonwort species, Cochlearia excelsa, was sequenced and a so-called pan genome reconstructed. It joins together different genome sequences and therefore shows the genetic variations between individuals and further species. To this end, more than 350 genomes of various Cochlearia species with different chromosome set numbers were analyzed. “Surprisingly, the results show that polyploids actually exhibit genomic structural variants with signals for possible local adaptation more frequently than diploid species,” explains Prof. Yant, a researcher in evolutionary genomics at the University of Nottingham (UK).

These structural mutations are concealed by the additional genome copies and are therefore protected from selection to a certain extent, because the accumulation of structural variants can also result in a loss of function. With their models, the international research team were further able to demonstrate that the polyploid-specific structural variants also appear in the very gene regions that could play a significant role in future climate adaptations. A detailed analysis of the genomic data showed that this mainly involves biological processes of seed germination or resistance against plant diseases, according to Dr Filip Kolář, who conducts research at Charles University in Prague and at the Czech Academy of Sciences.

It is, however, probably highly unlikely that the Cochlearia species found in Central Europe today will survive climate change in the end, as Prof. Koch stresses. “Especially the diploid Cochlearia excelsa cannot migrate further in higher and colder regions in the Austrian mountains, since this species of spoonwort has already reached the summit regions to some extent. The Pyrenees spoonwort from the Central European hill and mountain country will also find it difficult.” The researchers did show, however, that the entire gene pool especially in the polyploid cold specialists can survive, particularly in the northern regions of the Earth. The evolutionary history of these cruciferous plants thereby provides insights into how plants may be able to cope with climate change in the future.

The research work was conducted in particular within the framework of a grant from the European Research Council (ERC), an ERC Starting Grant for Levi Yant. The cooperating team from Heidelberg University developed the Cochlearia model system over the past 25 years with funding from the German Research Foundation. The findings were published in the journal “Nature Communications”.

END

How plant cold specialists can adapt to the environment

International team of evolutionary biologists investigate genomic underpinnings for the adaptive potential of spoonworts

2024-07-12

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Biomarkers reveal how patients with glaucoma may respond to treatment

2024-07-12

Markers in the blood that predict whether glaucoma patients are at higher risk of continued loss of vision following conventional treatment have been identified by researchers at UCL and Moorfields Eye Hospital.

Over 700,000 people in the UK have glaucoma and it is the leading cause of irreversible blindness worldwide. The condition occurs when the cells in the eye that help you see (called retinal ganglion cells) start to die.

The main risk factors for glaucoma are high eye pressure and older age.

Currently, all licenced treatments are designed to lower pressure in the eye – also known as intraocular pressure. However, some patients ...

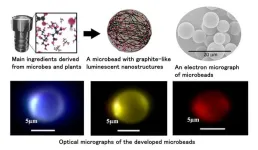

Microbeads with adaptable fluorescent colors from visible light to near-infrared

2024-07-12

1. A research team at NIMS has successfully developed an environmentally friendly, microspherical fluorescent material primarily made from citric acid. These microbeads emit various colors of light depending on the illuminating light and the size of the beads, which suggests a wide range of applications. Furthermore, the use of plant-derived materials allows for low-cost and energy-efficient synthesis.

2. Conventional luminescent devices commonly utilized thin films of compound semiconductors containing metals or sintered inorganic materials with rare earth elements. However, in a circular economy, there ...

Neighborhood disadvantage and prostate tumor RNA expression of stress-related genes

2024-07-12

About The Study: In this cross-sectional study, the expression of several stress-related genes in prostate tumors was higher among men residing in disadvantaged neighborhoods. This study is one of the first to suggest associations of neighborhood disadvantage with prostate tumor RNA expression. Additional research is needed in larger studies to replicate findings and further investigate interrelationships of neighborhood factors, tumor biology, and aggressive prostate cancer to inform interventions to reduce disparities.

Corresponding Author: To contact the corresponding author, ...

Screen media use and mental health of children and adolescents

2024-07-12

About The Study: This secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial found that a short-term reduction in leisure-time screen media use within families positively affected psychological symptoms of children and adolescents, particularly by mitigating internalizing behavioral issues and enhancing prosocial behavior. More research is needed to confirm whether these effects are sustainable in the long term.

Corresponding Author: To contact the corresponding author, Jesper Schmidt-Persson, Ph.D., email jesp@kp.dk.

To ...

Mediterranean diet and cardiometabolic biomarkers in children and adolescents

2024-07-12

About The Study: The findings of this study suggest that Mediterranean diet-based interventions may be useful tools to optimize cardiometabolic health among children and adolescents.

Corresponding Author: To contact the corresponding author, Jose Francisco Lopez-Gil, Ph.D., email josefranciscolopezgil@gmail.com.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.21976)

Editor’s Note: Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, author contributions ...

A chemical claw machine bends and stretches when exposed to vapors

2024-07-12

Scientists at King Abdullah University of Science and Technology (KAUST) in Saudi Arabia have developed a tiny “claw machine” that is able to pick up and drop a marble-sized ball in response to exposure to chemical vapors.

The findings, published July 12 in the journal Chem, point to a technique that can enable soft actuators—the parts of a machine that make it move—to perform multiple tasks without the need for additional costly materials. While existing soft actuators can be “one-trick ponies” restricted to one type of movement, this novel composite film contorts itself ...

Living in disadvantaged neighborhoods influences stress-related genes, which may contribute to aggressive prostate cancer in African American men

2024-07-12

BALTIMORE, MD, July 12, 2024 — Those living in disadvantaged neighborhoods have significantly higher activity of stress-related genes, new research suggests, which could contribute to higher rates of aggressive prostate cancer in African American men. The study, which was co-led by the University of Maryland School of Medicine (UMSOM) and Virginia Commonwealth University (VCU), was published today in JAMA Network Open.

African American men have a higher incidence of prostate cancer and are more than twice as likely to die from the disease than White men in the U.S. They are often diagnosed with an ...

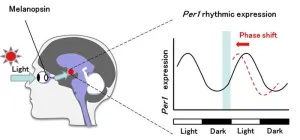

Melanopsin DNA aptamers can regulate input signals of mammalian circadian rhythms by altering the phase of the molecular clock

2024-07-12

Overview:

DNA aptamers of melanopsin that regulate the clock hands of biological rhythms were developed by the Toyohashi University of Technology and the National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology (AIST) group.

DNA aptamers can specifically bind to biomolecules to modify their function, potentially making them ideal oligonucleotide therapeutics. We screened the DNA aptamer melanopsin (OPN4), a blue light photopigment in the retina that plays a key role in the use of light signals to reset the phase of circadian rhythms in the central clock.

First, 15 DNA aptamers of melanopsin (Melapts) were identified following eight rounds of Cell-SELEX ...

Challenges and prospects for post-conflict peacebuilding in urban settings

2024-07-12

Wars and conflicts leave devastating destruction in their wake. With so many conflicts now taking place in urban environments, scientists are studying how post-conflict peacebuilding happens in these urban settings. Dahlia Simangan, an associate professor at The IDEC Institute, Hiroshima University, has analyzed the case of Marawi, a city in the Philippines, to better understand the urban environment’s influence on post-siege reconstruction and peacebuilding. This study contributes to a more comprehensive understanding of peacebuilding by integrating conventional peacebuilding components and urban characteristics.

The findings are published ...

Neutrons give a hot new way to measure the temperature of electronic components

2024-07-12

Osaka, Japan – From LEDs to batteries, our lives are full of electronics, and there is a constant push to make them more efficient and reliable. But as components become increasingly sophisticated, getting reliable temperature measurements of specific elements inside an object can be a challenge.

This is problematic because measuring a device’s temperature is vital for monitoring its performance or designing the materials from which it’s manufactured. Now, in a new study led by Osaka ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

A kaleidoscope of cosmic collisions: the new catalogue of gravitational signals from LIGO, Virgo and KAGRA

New catalog more than doubles the number of gravitational-wave detections made by LIGO, Virgo, and KAGRA observatories

Antifibrotic drug shows promise for premature ovarian insufficiency

Altered copper metabolism is a crucial factor in inflammatory bone diseases

Real-time imaging of microplastics in the body improves understanding of health risks

Reconstructing the world’s ant diversity in 3D

UMD entomologist helps bring the world’s ant diversity to life in 3D imagery

ESA’s Mars orbiters watch solar superstorm hit the Red Planet

The secret lives of catalysts: How microscopic networks power reactions

Molecular ‘catapult’ fires electrons at the limits of physics

Researcher finds evidence supporting sucrose can help manage painful procedures in infants

New study identifies key factors supporting indigenous well-being

Bureaucracy Index 2026: Business sector hit hardest

ECMWF’s portable global forecasting model OpenIFS now available for all

Yale study challenges notion that aging means decline, finds many older adults improve over time

Korean researchers enable early detection of brain disorders with a single drop of saliva!

Swipe right, but safer

Duke-NUS scientists identify more effective way to detect poultry viruses in live markets

Low-intensity treadmill exercise preconditioning mitigates post-stroke injury in mouse models

How moss helped solve a grave-robbing mystery

How much sleep do teens get? Six-seven hours.

Patients regain weight rapidly after stopping weight loss drugs – but still keep off a quarter of weight lost

GLP-1 diabetes drugs linked to reduced risk of addiction and substance-related death

Councils face industry legal threats for campaigns warning against wood burning stoves

GLP-1 medications get at the heart of addiction: study

Global trauma study highlights shared learning as interest in whole blood resurges

Almost a third of Gen Z men agree a wife should obey her husband

Trapping light on thermal photodetectors shatters speed records

New review highlights the future of tubular solid oxide fuel cells for clean energy systems

Pig farm ammonia pollution may indirectly accelerate climate warming, new study finds

[Press-News.org] How plant cold specialists can adapt to the environmentInternational team of evolutionary biologists investigate genomic underpinnings for the adaptive potential of spoonworts