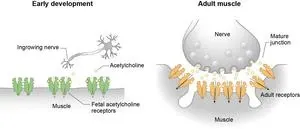

(Press-News.org) The connections between the nervous system and muscles develop differently across the kingdom of life. It takes newborn humans roughly a year to develop the proper muscular systems that support the ability to walk, while cows can walk mere minutes after birth and run not long after.

University of California San Diego researchers, using powerful new visualization technologies, now have a clear picture of why these two scenarios develop so differently. The results offer new insight into understanding muscle contraction in humans that may help in developing future treatments for muscular diseases.

“In this study we set out to understand the molecular details involved in muscle contraction at the point of contact between motor neurons and skeletal muscles, which are the muscles we consciously control,” said School of Biological Sciences Professor Ryan Hibbs, of the new study published in Nature. “We have discovered how the muscle protein changes in its composition during development, which is important in the context of diseases that cause progressive muscle weakness.”

The ability of skeletal muscles to contract allows for our bodies to move — from walking and jumping to breathing and blinking our eyes. All skeletal muscle contractions originate at the junction between motor neurons, which originate in the spinal cord and brainstem, and muscle fibers. It’s here that neurons release a transmitter chemical called acetylcholine. These molecules bind to a protein receptor on the cells of muscles, triggering an opening in the cell membrane. Electrical currents flow into the cell, which causes muscles to contract.

The way neurons release chemicals that communicate with muscles has been a model system studied for more than a century. But a missing piece of this system has been visual depictions of how the process works. What does the structure of the muscle receptor protein that opens up look like?

To find out, Hibbs, study first author Huanhuan Li, a postdoctoral scholar, and Jinfeng Teng, a research data analyst, tapped cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) technology based at UC San Diego’s new Goeddel Family Technology Sandbox, a hub for cutting-edge research instruments. Cryo-EM leverages ultra-powerful microscopes to capture images of molecules that are “frozen” in place.

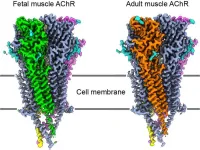

The results featured the first visualizations of the 3-D structure of the muscle acetylcholine receptor. Since human tissue is difficult to obtain for such muscle contraction studies, the researchers accessed fetal tissue samples from cow skeletal muscles. In order to isolate the receptor in the samples, the researchers turned to an unlikely source: snake venom. A poisonous snake neurotoxin that paralyzes prey was used to latch onto the muscle receptors in the cow samples, allowing the researchers to isolate the receptors to study them. The cryo-EM visualizations then allowed the researchers to witness how the receptor development process unfolds.

Along with the new data came a serendipitous finding. The researchers discovered that they could see the structures of both fetal and adult receptors from the same fetal cow tissue samples.

“We hoped to see the structure of the receptor and we did see that, but we also saw that there were two different versions of it,” said Hibbs. “That was a surprise.”

In retrospect, the discovery of two receptor types makes sense, according to Hibbs. Since calves are developing in utero, the fetal receptors were expected. To walk like an adult shortly after birth, they start building adult nerve-muscle connections much earlier in development.

“This discovery explains how animals like cows that need to walk on the day they are born form mature neuromuscular junctions before birth, unlike humans, who have poor muscle coordination for months after birth,” said Hibbs. “Being able to see the receptor details allows us to connect their differences to how one allows for nerve-muscle connection and the other allows for muscle contraction.”

The findings of the study are already being applied to investigations of muscle-based disorders, such as congenital myasthenic syndromes (CMS) that result in muscle weakness. A common autoimmune disease known as myasthenia gravis involves antibodies that mistakenly attack the muscle acetylcholine receptor, causing weak skeletal muscles.

“This new level of insight into the muscle receptor will help researchers understand how mutations in its gene cause disease, and may facilitate personalized treatment for individual patients with different pathologies in the future,” said lead author Li.

END

Unraveling a key junction underlying muscle contraction

Researchers capture the first 3-D images of the structure of a key muscle receptor, setting the stage for possible future treatments for muscular disorders

2024-07-31

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

New method recovers phosphorus from wastewater to power the future of lithium-iron phosphate batteries

2024-07-31

In a recent study published in Engineering, a research team from the Shenzhen Engineering Research Laboratory for Sludge and Food Waste Treatment and Resource Recovery has introduced a pioneering method to tackle the critical global issue of phosphorus (P) scarcity. Their innovative approach leverages municipal wastewater to produce phosphorus vital for the manufacture of lithium iron phosphate (LiFePO4) batteries, a key component in the rapidly growing electric vehicle market.

As the demand for LiFePO4 batteries ...

SwRI awarded $35.7 million to support cryptologic systems for U.S. Navy

2024-07-31

SAN ANTONIO — July 31, 2024 —Southwest Research Institute will provide engineering and equipment support for advanced cryptologic technology for shipboard and airborne platforms as part of a $35.7 million contract with the U.S. Navy. The five-year contract will deliver services from June 2024 through June 2029, with the option for the U.S. Navy to add $14 million and extend the contract through 2031.

SwRI develops electronic warfare (EW) technology to detect, intercept and disrupt a range of signals on the electromagnetic spectrum, supporting efforts to thwart ...

With biodiversity under threat, scientists suggest the need for a new biorepository—on the moon

2024-07-31

With numerous species facing extinction, an international team of researchers has proposed an innovative solution to protect the planet's biodiversity: a lunar biorepository. This concept, detailed in a recent article in the journal BioScience, is aimed at creating a passive, long-lasting storage facility for cryopreserved samples of Earth's most at-risk animal species.

Led by Dr. Mary Hagedorn of the Smithsonian's National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute, the team envisions taking advantage of the Moon's naturally cold temperatures, particularly in permanently shadowed regions near the poles, where temperatures remain consistently below –196 degrees ...

Strong El Nino makes European winters easier to forecast

2024-07-31

Heavy rain and flooding in Brazil in November could tell forecasters whether December, January and February in Britain will be cold and dry or mild and wet.

This is because forecasting European winter weather patterns months in advance is made simpler during years of strong El Niño or La Niña events in the tropical Pacific Ocean, a new study has found.

A strong El Nino or La Nina in the Pacific Ocean can bring big changes in temperatures, wind patterns and rainfall patterns to South America. When ...

MD Anderson and collaborators to launch project studying T cells on International Space Station

2024-07-31

HOUSTON ― The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center and collaborators are initiating a research project that will send T cells to the International Space Station (ISS) to study the effects of prolonged microgravity on cell differentiation, activation, memory and exhaustion. These results will be further analyzed on Earth to uncover signaling pathways and identify potential immune targets that can improve treatment strategies for patients with cancer and other diseases.

To accomplish this work, MD Anderson researchers ...

Chameleon testbed secures $12 million in funding for phase 4: Expanding frontiers in computer science research

2024-07-31

Chameleon, led by Senior Scientist Kate Keahey from Argonne National Laboratory, has been a cornerstone of CS research and education for nearly a decade. The platform has served over 10,000 users, contributing to more than 700 research publications. Chameleon has now secured an additional $12 million in funding from the U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF) to roll out its next four-year phase. With this new funding, Chameleon will continue to innovate and support its growing community, enabling groundbreaking discoveries in CS systems research.

ABOUT CHAMELEON: A PLATFORM FOR INNOVATION

Chameleon is a large-scale, deeply reconfigurable experimental ...

For bigger muscles push close to failure, for strength, maybe not

2024-07-31

When performing resistance training such as lifting weights, there’s a lot of interest in how close you push yourself to failure – the point where you can’t do another rep – and how it affects your results.

While research has looked at this concept in different ways, to date, no meta-analysis has explored the pattern (i.e., linear or non-linear) of how the distance from failure (measured by repetitions in reserve) affects changes in muscle strength and size.

As such, it’s ...

Improving Alzheimer’s disease imaging — with fluorescent sensors

2024-07-31

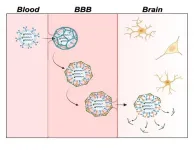

Neurotransmitter levels in the brain can indicate brain health and neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s. However, the protective blood-brain barrier (BBB) makes delivering fluorescent sensors that can detect these small molecules to the brain difficult. Now, researchers in ACS Central Science demonstrate a way of packaging these sensors for easy passage across the BBB in mice, allowing for improved brain imaging. With further development, the technology could help advance Alzheimer’s disease diagnosis and treatment.

It is common for neurotransmitter levels ...

Most blood thinner dosing problems happen after initial prescription

2024-07-31

Millions of Americans take anticoagulants, commonly known as blood thinners. These medications work to prevent blood clots that cause heart attack and stroke.

More than two-thirds of those people take a type of blood thinner called a direct oral anticoagulant. DOACs, such as rivaroxaban (brand name Xarelto) and apixaban (brand name Eliquis), are under- or over-prescribed in up to one in eight patents.

These prescribing issues can have life threatening consequences, and they most often occur after a provider writes the initial prescription, according to a study led by Michigan Medicine.

“Direct oral anticoagulants may be viewed ...

AI boosts the power of EEGs, enabling neurologists to quickly, precisely pinpoint signs of dementia

2024-07-31

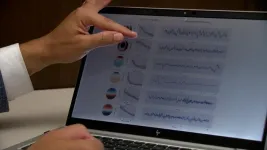

ROCHESTER, Minn. — Mayo Clinic scientists are using artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning to analyze electroencephalogram (EEG) tests more quickly and precisely, enabling neurologists to find early signs of dementia among data that typically go unexamined.

The century-old EEG, during which a dozen or more electrodes are stuck to the scalp to monitor brain activity, is often used to detect epilepsy. Its results are interpreted by neurologists and other experts trained to spot patterns among the test's squiggly waves.

In new research published in Brain Communications, scientists at the Mayo Clinic Neurology AI Program (NAIP) demonstrate ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Alkali cation effects in electrochemical carbon dioxide reduction

Test platforms for charging wireless cars now fit on a bench

$3 million NIH grant funds national study of Medicare Advantage’s benefit expansion into social supports

Amplified Sciences achieves CAP accreditation for cutting-edge diagnostic lab

Fred Hutch announces 12 recipients of the annual Harold M. Weintraub Graduate Student Award

Native forest litter helps rebuild soil life in post-mining landscapes

Mountain soils in arid regions may emit more greenhouse gas as climate shifts, new study finds

Pairing biochar with other soil amendments could unlock stronger gains in soil health

Why do we get a skip in our step when we’re happy? Thank dopamine

UC Irvine scientists uncover cellular mechanism behind muscle repair

Platform to map living brain noninvasively takes next big step

Stress-testing the Cascadia Subduction Zone reveals variability that could impact how earthquakes spread

We may be underestimating the true carbon cost of northern wildfires

Blood test predicts which bladder cancer patients may safely skip surgery

Kennesaw State's Vijay Anand honored as National Academy of Inventors Senior Member

Recovery from whaling reveals the role of age in Humpback reproduction

Can the canny tick help prevent disease like MS and cancer?

Newcomer children show lower rates of emergency department use for non‑urgent conditions, study finds

Cognitive and neuropsychiatric function in former American football players

From trash to climate tech: rubber gloves find new life as carbon capturers materials

A step towards needed treatments for hantaviruses in new molecular map

Boys are more motivated, while girls are more compassionate?

Study identifies opposing roles for IL6 and IL6R in long-term mortality

AI accurately spots medical disorder from privacy-conscious hand images

Transient Pauli blocking for broadband ultrafast optical switching

Political polarization can spur CO2 emissions, stymie climate action

Researchers develop new strategy for improving inverted perovskite solar cells

Yes! The role of YAP and CTGF as potential therapeutic targets for preventing severe liver disease

Pancreatic cancer may begin hiding from the immune system earlier than we thought

Robotic wing inspired by nature delivers leap in underwater stability

[Press-News.org] Unraveling a key junction underlying muscle contractionResearchers capture the first 3-D images of the structure of a key muscle receptor, setting the stage for possible future treatments for muscular disorders