(Press-News.org) Could This New Drug Turn Back the Clock on Multiple Sclerosis?

Ten years of work, and a little help from the green mamba snake, has resulted in a promising new drug that is already being tested in clinical trials.

Multiple sclerosis (MS) degrades the protective insulation around nerve cells, leaving their axons, which carry electrical impulses, exposed like bare wires. This can cause devastating problems with movement, balance and vision; and without treatment, it can lead to paralysis, loss of independence and a shortened lifespan.

Now, scientists at UC San Francisco and Contineum Therapeutics have developed a drug that spurs the body to replace the lost insulation, which is called myelin. If it works in people, it could be a way to reverse the damage caused by the disease.

The new therapy, called PIPE-307, targets an elusive receptor on certain cells in the brain that prompts them to mature into myelin-producing oligodendrocytes. Once the receptor is blocked, the oligodendrocytes spring into action, wrapping themselves around the axons to form a new myelin sheath.

It was crucial to prove that the receptor, known as M1R, was present on the cells that can repair damaged fibers. Contineum scientist and first author Michael Poon, PhD, figured this out using a toxin found in green mamba snake venom.

The work, which appears Aug. 2 in PNAS, caps a decade of work by UCSF scientists Jonah Chan, PhD, and Ari Green, MD. Chan led the team to discover in 2014 that an obscure antihistamine known as clemastine could induce remyelination, which no one knew was possible.

“Ten years ago, we discovered one way that the body can regenerate its myelin in response to the right molecular signal, winding back the consequences of MS,” said Chan, a Debbie and Andy Rachleff Distinguished Professor of Neurology at UCSF and senior author of the paper. “By carefully studying the biology of remyelination, we’ve developed a precise therapy to activate it – the first of a new class of MS therapies.”

A dirty drug creates a clean opening

The original breakthrough came when Chan invented a method to screen drugs for their ability to instigate remyelination. The screen identified a group drugs, including clemastine, that had one thing in common: they blocked muscarinic receptors.

Clemastine's benefits begin with its effect on oligodendrocyte precursor cells (OPCs). These cells stay dormant in the brain and spinal cord until they sense injured tissue. Then they move in and give rise to oligodendrocytes, which produce myelin.

For some reason during MS, OPCs gather around decaying myelin but fail to rebuild it. Chan figured out that clemastine activated OPCs by blocking muscarinic receptors, enabling the OPCs to mature into myelin-producing oligodendrocytes.

Nerves and their myelin are notoriously hard to repair, whether due to MS, dementia or other injury. Green and Chan carried out a trial of clemastine in patients with MS, and it was a success – the first time that a drug showed the capacity to restore the myelin lost in MS. Despite being safe to use, however, clemastine was only modestly effective.

“Clemastine is not a targeted drug, affecting several different pathways in the body,” said Green, Chief of the Division of Neuroimmunology and Glial Biology in the UCSF Department of Neurology and co-author of the paper. “But from the get-go, we saw that its pharmacology with muscarinic receptors could point us toward the next generation of restorative therapies in MS.”

A snake venom toxin illuminates the right target

The researchers continued using clemastine to understand the curative potential of regenerating myelin in MS. They developed a series of tools to monitor remyelination, both in animal models of MS and in MS patients, showing that the benefits seen with clemastine came from remyelination – and pointing the way for how new drugs should be tested and evaluated.

They also found that clemastine’s benefits came from blocking just one of the five muscarinic receptors, M1R, but the effect on M1R was middling, and the drug also affected the other receptors. The ideal drug would need to zero in on M1R.

At this point, the UCSF scientists needed an industry partner to advance the project. Ultimately, Contineum Therapeutics (then known as Pipeline Therapeutics) was formed to take a meticulous approach to creating that ideal drug. Chan and Green helped the company confirm that M1R was the right target for a remyelinating drug, and then make a drug that blocked it exclusively.

Poon, a biologist at Contineum, realized that MT7, a toxin found in the venom of the deadly green mamba snake, could reveal exactly where M1R was in the brain.

“We needed to prove, beyond doubt, that M1R was present in OPCs that were near the damage caused by MS,” Poon said. “MT7, which is exquisitely selective for M1R, fit the bill.”

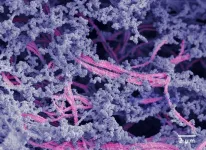

Poon used MT7 to engineer a molecular label for M1R that revealed rings of OPCs gathering around damage in a mouse model of MS and in human MS tissue.

Developing a clinic-ready drug

A team of medicinal chemists at Contineum, led by Austin Chen, PhD, then got to work on the drug that Chan and Green envisioned, designing PIPE-307 to potently block M1R and get into the brain.

The researchers tested the effects of the new drug on OPCs grown in petri dishes and the animal models of MS using Chan’s and Green’s methods for tracking remyelination. PIPE-307 blocked the M1R receptor much better than clemastine; prompted OPCs to mature into oligodendrocytes and begin myelinating nearby axons; and it crossed the blood-brain barrier.

But most tellingly, it reversed the degradation seen in a mouse model of MS.

“A drug might seem to work in these abstract scenarios, affecting the right receptor or cell, but the key finding was actual recovery of nervous system function,” Chan said.

In 2021, PIPE-307 passed a Phase I clinical trial, demonstrating its safety. It is currently being tested in MS patients in Phase II.

If it succeeds, it could transform how MS is treated.

“Every patient we diagnose with MS comes in with some degree of pre-existing injury,” Green said. “Now we might have a chance to not just stop their disease, but to also heal.”

Other authors are Kym I Lorrain, Karin J Stebbins, Geraldine C Edu, Alexander R Broadhead, Ariana J Lorenzana, Jeffrey R Roppe, Jill M Baccei, Christopher S Baccei, and Daniel S Lorrain, all employees of Contineum Therapeutics.

Funding: The work was partially funded by the NIH/National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (grants R01NS115746 and R01MH125515).

Disclosures: All Contineum Therapeutics employees hold financial shares of the company. Chan and Green also hold financial shares in Contineum Therapeutics but no longer serve in any role. Contineum Therapeutics owns patent rights to PIPE-307.

About UCSF: The University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) is exclusively focused on the health sciences and is dedicated to promoting health worldwide through advanced biomedical research, graduate-level education in the life sciences and health professions, and excellence in patient care. UCSF Health, which serves as UCSF's primary academic medical center, includes top-ranked specialty hospitalsand other clinical programs, and has affiliations throughout the Bay Area. UCSF School of Medicine also has a regional campus in Fresno. Learn more at ucsf.edu, or see our Fact Sheet.

###

Follow UCSF

ucsf.edu | Facebook.com/ucsf | YouTube.com/ucsf

END

Could this new drug turn back the clock on multiple sclerosis?

2024-08-05

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Greenland fossil discovery reveals increased risk of sea-level catastrophe

2024-08-05

The story of Greenland keeps getting greener—and scarier.

A new study provides the first direct evidence that the center—not just the edges—of Greenland’s ice sheet melted away in the recent geological past and the now-ice-covered island was then home to a green, tundra landscape.

A team of scientists re-examined a few inches of sediment from the bottom of a two-mile-deep ice core extracted at the very center of Greenland in 1993—and held for 30 years in a Colorado storage facility. They were amazed to discover ...

New biomaterial regrows damaged cartilage in joints

2024-08-05

Northwestern University scientists have developed a new bioactive material that successfully regenerated high-quality cartilage in the knee joints of a large-animal model.

Although it looks like a rubbery goo, the material is actually a complex network of molecular components, which work together to mimic cartilage’s natural environment in the body.

In the new study, the researchers applied the material to damaged cartilage in the animals’ knee joints. Within just six months, the researchers observed evidence of enhanced repair, including ...

Horse miscarriages offer clues to causes of early human pregnancy loss

2024-08-05

ITHACA, N.Y. – A study of horses – which share many important similarities with humans in their chromosomes and pregnancies – revealed that 42% of miscarriages and spontaneous abortions in the first two months of pregnancy were due to complications from an extra set of chromosomes, a condition called triploidy.

“Over that embryonic period [up to eight weeks from conception], triploidy had rarely been reported in mammals outside of women,” said Mandi de Mestre, professor of equine medicine at Cornell University. “The study tells us that over the first six weeks ...

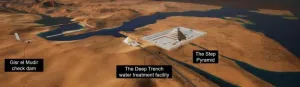

Hydraulic lift technology may have helped build Egypt’s iconic Pyramid of Djoser

2024-08-05

The Pyramid of Djoser, the oldest of Egypt’s iconic pyramids, may have been built with the help of a unique hydraulic lift system, according to a study published August 5, 2024, in the open-access journal PLOS ONE by Xavier Landreau from CEA Paleotechnic Institute, France, and colleagues. The new study suggests that water may have been able to flow into two shafts located inside the pyramid itself, where that water could have been used to help raise and lower a float used to carry the building stones.

The Pyramid of Djoser, also known as the Step Pyramid, is believed ...

Honey added to yogurt supports probiotic cultures for digestive health

2024-08-05

URBANA, Ill. – If you enjoy a bowl of plain yogurt in the morning, adding a spoonful of honey is a delicious way to sweeten your favorite breakfast food. It also supports the probiotic cultures in the popular fermented dairy product, according to two new studies from the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign.

“We were interested in the culinary pairing of yogurt and honey, which is common in the Mediterranean diet, and how it impacts the gastrointestinal microbiome,” said Hannah Holscher, associate professor in the Department of Food ...

Tradition meets transformation for Maasai women

2024-08-05

Few communities reveal both the challenges and opportunities presented by cultural globalism more than Maasai communities in northern Tanzania. Traditionally pastoralists, the Maasai ethnic group’s social structure is historically patriarchal, with a man’s prestige measured by the size of his family and by the livestock he owns.

The shrinking world has brought change: Urban centers and the promise of jobs are luring young Maasai from communities, and new technologies such as mobile phones are shifting social patterns and structures that ...

Ochsner Health nurses named to the “Great 100 Nurses of Louisiana” 2024 List

2024-08-05

NEW ORLEANS, La. – Ochsner Health proudly announces that 21 Ochsner nurses have been named to the 2024 Great 100 Nurses of Louisiana list by the Great 100 Nurses Foundation. This recognition highlights the contributions and commitment to excellence demonstrated by Ochsner’s nursing staff.

The Great 100 Nurses Foundation was established to honor nurses in Louisiana, North Carolina, Texas and Oklahoma. Each year, the foundation selects 100 nurses throughout Louisiana based on their concern for humanity, ...

Improved chemokine homing enhances CAR T–cell therapy for osteosarcoma

2024-08-05

(MEMPHIS, Tenn. – August 5, 2024) Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T–cell immunotherapy re-engineers a patient’s immune cells to target cancer cells. While successful in some types of leukemia, the approach has yet to realize its potential against pediatric solid tumors. Scientists at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital have identified a way to improve CAR T–cell homing – a T cell’s ability to navigate effectively to a tumor – for osteosarcoma. Improved homing is a necessary step in designing more successful CAR T–cell therapies. The results were published today in Clinical Cancer ...

Forecasting climate’s impact on a debilitating disease

2024-08-05

In Brazil, climate and other human-made environmental changes threaten decades-long efforts to fight a widespread and debilitating parasitic disease. Now, a partnership between researchers from Stanford and Brazil is helping to proactively predict these impacts.

Schistosomiasis, spread by freshwater snails, affects more than 200 million people in many tropical regions of the world. It can cause stomach pain and irreversible consequences such as enlarged liver and cancer. Public health officials worry that deforestation, rapid urban sprawl, and changing rainfall patterns – such as ...

Deaths from advanced lung cancer have dropped significantly since immunotherapy became standard-of-care

2024-08-05

Since the first immunotherapy drug to boost the body’s immune response against advanced lung cancer was introduced in the United States in 2015, survival rates of patients with the disease have improved significantly. That’s the conclusion of a recent real-world study published by Wiley online in CANCER, a peer-reviewed journal of the American Cancer Society.

For the research, a team led by Dipesh Uprety, MD, FACP, of the Barbara Ann Karmanos Cancer Institute and the Wayne State University School of Medicine, analyzed data from the National Cancer Institute Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database, which compiles cancer-related data ...