(Press-News.org) or many plants, more branches means more fruit. But what causes a plant to grow branches? New research from the University of California, Davis shows how plants break down the hormone strigolactone, which suppresses branching, to become more “bushy.” Understanding how strigolactone is regulated could have big implications for many crop plants.

The study was published August 1 in Nature Communications.

“Being able to manipulate strigolactone could also have implications beyond plant architecture, including on a plant’s resilience to drought and pathogens,” said senior author Nitzan Shabek, an associate professor in the UC Davis Department of Plant Biology who specializes in biochemistry and structural biology.

Strigolactone’s hormonal role was discovered only in 2008, and Shabek describes it as “the new kid on the block” for plant hormone research. In addition to regulating branching behavior, strigolactone also promotes beneficial interactions belowground between mycorrhizal fungi and plant roots, and helps plants respond to stresses such as drought and high salinity.

Though scientists know a lot about how plants synthesize strigolactones and other hormones, very little is known about how plants break them down. Recent research has suggested that enzymes called carboxylesterases, which exist in all kingdoms of life, including humans, might be involved in degrading strigolactone. Plants produce more than 20 types of carboxylesterases, but only two forms in particular, CXE15 and CX20, have been linked to strigolactone. However, this link was only speculative, and Shabek’s team wanted to know more about how this degradation works.

“Our lab is interested in mechanisms, meaning we don’t want to just know that a car can drive, we want to know how it's driving; what's going on inside the engine,” said Shabek.

Deciphering an enzyme’s engine

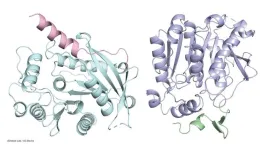

To investigate whether CXE15 and CX20 really are involved in strigolactone regulation, the researchers began by building 3D models of the enzymes’ molecular structure. This work was kickstarted by undergraduate researcher Linyi Yan, who grew and purified the carboxylesterase proteins in the lab.

That student-led project very quickly became something bigger, Shabek said.

Postdoctoral fellow Malathy Palayam used x-ray crystallography and computer simulations to solve the enzymes’ three-dimensional atomic structure, and performed biochemical experiments to compare how the two enzymes might degrade the hormone.

These experiments showed that CXE15 was much more efficient at breaking down strigolactone than CXE20, which binds to strigolactone but does not degrade it effectively. Their 3D models revealed something new: that a specific region of CXE15 actually allowed the enzyme to change its shape.

“CXE15 is a very effective enzyme—it can completely destroy the strigolactone molecule in milliseconds,” said Shabek. “When we zoomed in, we realized that there is a dynamic area in the enzyme’s structure which is required for it to function in this way.”

A dynamic enzyme

By examining CXE15’s structure, Shabek and his collaborators identified specific amino acids that allow the enzyme to dynamically bind to strigolactone. Then, to confirm that these amino acids were indeed responsible for the enzyme’s efficiency, they genetically engineered a mutant version of the enzyme with an altered dynamic region. The mutant version showed a reduced capacity to degrade strigolactone both in vitro and when the team tested it in Nicotiana benthamiana plants.

Shabek says the next steps will be to investigate how carboxylesterase enzymes are produced in different plant tissues, like roots and stems.

“In this study we were really interested in elucidating these enzymes’ mechanism and structure, but future studies can begin investigating how they affect plant growth and development,” Shabek said.

Additional authors on the study are: Ugrappa Nagalakshmi, Amelia K. Gilio and Savithramma Dinesh-Kumar, UC Davis; David Cornu and Francois-Didier Boyer, Universite Paris-Saclay, France.

The work was supported by the National Science Foundation and the U.S. Department of Energy.

END

How plants become bushy, or not

New study sheds light on hormone that controls branching

2024-08-06

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Research spotlight: Identifying potential new protein targets for melanoma therapeutics

2024-08-06

How would you summarize your study for a lay audience?

Some proteins, such as programmed cell death protein 1 (PD1), can stop the immune system from attacking cancer cells and, therefore, support the growth of cancer. Therapies targeting these proteins can be highly effective, but tumors can become resistant.

We applied a method to detect proteins on a single–cell level to uncover human carcinoembryonic antigen cell adhesion molecule 1 (CEACAM1) patterns in melanoma. We found that increased ...

Damon Runyon Cancer Research Foundation awards $5.2 million to top clinical investigators

2024-08-06

Damon Runyon Cancer Research Foundation awards $5.2 million to top clinical investigators

The Damon Runyon Cancer Research Foundation has named six new Damon Runyon Clinical Investigators. The recipients of this prestigious award are outstanding, early-career physician-scientists conducting patient-oriented cancer research at major research centers under the mentorship of the nation's leading scientists and clinicians.

The Clinical Investigator Award program was designed to increase the number of physicians capable of translating scientific discoveries into new treatments for cancer patients. Each Awardee will receive $600,000 over three years, ...

Good outcomes 10 years after surgery for ectopic bone in thoracic spine

2024-08-06

August 6, 2024 — Thoracic ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament (TOPLL) is a rare condition associated with ectopic bone formation in the thoracic spine. A long-term follow-up study from Japan shows significant and lasting improvement in outcomes with posterior decompression and fixation surgery for patients with T-OPLL, reports The Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery. The journal is published in the Lippincott portfolio by Wolters Kluwer.

"Surgical treatment of T-OPLL is effective in improving neurological function, quality ...

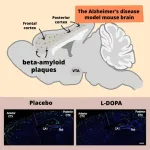

Dopamine treatment alleviates symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease

2024-08-06

A new way to combat Alzheimer’s disease has been discovered by Takaomi Saido and his team at the RIKEN Center for Brain Science (CBS) in Japan. Using mice with the disease, the researchers found that treatment with dopamine could alleviate physical symptoms in the brain as well as improve memory. Published in the scientific journal Science Signaling on August 6, the study examines dopamine’s role in promoting the production of neprilysin, an enzyme that can break down the harmful plaques in the brain that are the ...

Do your supplements contain potentially hepatoxic botanicals?

2024-08-06

Millions of Americans consume supplements that contain potentially hepatoxic botanical ingredients, according to a study from University of Michigan researchers.

Over a 30-day period, 4.7% of the adults surveyed in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey conducted from 2017 to 2020 took herbal and dietary supplements containing at least one of the botanicals of interest: turmeric; green tea; ashwagandha; black cohosh; garcinia cambogia; and red yeast rice containing products.

The resulting paper, “Estimated Exposure ...

No room for nuance in polarized political climate: SFU study

2024-08-06

Sometimes you just can’t win, and that goes double for people navigating the increasingly polarized political landscape in the United States.

Having nuanced opinions of politics in the U.S. turns out to be a very lonely, and unpopular, road, according to a recent study from a research team that includes assistant professor Aviva Phillipp-Muller from Simon Fraser University’s Beedie School of Business.

Published in the Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, the study found that people who express ambivalence about political topics – ranging from COVID-19 mask mandates, immigration and the death ...

What happens to your brain when you drink with friends?

2024-08-06

EL PASO, Texas (Aug. 6, 2024) – Grab a drink with friends at happy hour and you’re likely to feel chatty, friendly and upbeat. But grab a drink alone and you may experience feelings of depression. Researchers think they now know why this happens.

“Social settings influence how individuals react to alcohol, yet there is no mechanistic study on how and why this occurs,” said Kyung-An Han, Ph.D., a biologist at The University of Texas at El Paso who uses fruit flies to study alcoholism.

Now, Han and a team of UTEP faculty and students have taken a key step in understanding the neurobiological process behind social drinking and how it boosts ...

University of Houston researchers create new treatment and vaccine for flu and various coronaviruses

2024-08-06

A team of researchers, led by the University of Houston, has discovered two new ways of preventing and treating respiratory viruses. In back-to-back papers in Nature Communications, the team - from the lab of Navin Varadarajan, M.D. Anderson Professor of William A. Brookshire Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering - reports the development and validation of NanoSTING, a nasal spray, as a broad-spectrum immune activator for controlling infection against multiple respiratory viruses; and the development of NanoSTING-SN, a pan-coronavirus nasal vaccine, that can protect against infection and disease by all members of the coronavirus family.

NanoSTING ...

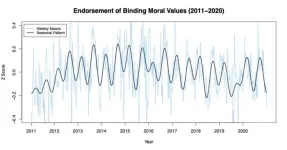

People's moral values change with the seasons

2024-08-06

A new UBC study has revealed regular seasonal shifts in people’s moral values.

The finding has potential implications for politics, law and health—including the timing of elections and court cases, as well as public response to a health crisis.

The research published this week in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) analyzed survey responses from more than 230,000 people in the U.S. over 10 years and revealed that people’s embrace of certain moral ...

Researchers reveal atomic-scale details of catalysts’ active sites

2024-08-06

The chemical and energy industries depend upon catalysts to drive the reactions used to create their products. Many important reactions use heterogeneous catalysts — meaning that the catalysts are in a different phase of matter than the substances they are reacting with, such as solid platinum reacting with gases in an automobile’s catalytic converter.

Scientists have investigated the surface of well-defined single crystals, illuminating the mechanisms underlying many chemical reactions. However, there is much more to be learned. For heterogeneous catalysts, their 3D atomic structure, their chemical composition and the nature of ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

New book captures hidden toll of immigration enforcement on families

New record: Laser cuts bone deeper than before

Heart attack deaths rose between 2011 and 2022 among adults younger than age 55

Will melting glaciers slow climate change? A prevailing theory is on shaky ground

New treatment may dramatically improve survival for those with deadly brain cancer

Here we grow: chondrocytes’ behavior reveals novel targets for bone growth disorders

Leaping puddles create new rules for water physics

Scientists identify key protein that stops malaria parasite growth

Wildfire smoke linked to rise in violent assaults, new 11-year study finds

New technology could use sunlight to break down ‘forever chemicals’

Green hydrogen without forever chemicals and iridium

Billion-DKK grant for research in green transformation of the built environment

For solar power to truly provide affordable energy access, we need to deploy it better

Middle-aged men are most vulnerable to faster aging due to ‘forever chemicals’

Starving cancer: Nutrient deprivation effects on synovial sarcoma

Speaking from the heart: Study identifies key concerns of parenting with an early-onset cardiovascular condition

From the Late Bronze Age to today - Old Irish Goat carries 3,000 years of Irish history

Emerging class of antibiotics to tackle global tuberculosis crisis

Researchers create distortion-resistant energy materials to improve lithium-ion batteries

Scientists create the most detailed molecular map to date of the developing Down syndrome brain

Nutrient uptake gets to the root of roots

Aspirin not a quick fix for preventing bowel cancer

HPV vaccination provides “sustained protection” against cervical cancer

Many post-authorization studies fail to comply with public disclosure rules

GLP-1 drugs combined with healthy lifestyle habits linked with reduced cardiovascular risk among diabetes patients

Solved: New analysis of Apollo Moon samples finally settles debate about lunar magnetic field

University of Birmingham to host national computing center

Play nicely: Children who are not friends connect better through play when given a goal

Surviving the extreme temperatures of the climate crisis calls for a revolution in home and building design

The wild can be ‘death trap’ for rescued animals

[Press-News.org] How plants become bushy, or notNew study sheds light on hormone that controls branching