(Press-News.org) Every year, life-threating invasive fungal infections afflict more than 2 million individuals globally. Mortality rates for these infections are high, even when patients receive treatment.

Aspergillus fumigatus, the most frequent cause of invasive fungal infection in people with suppressed immune systems, is responsible for approximately 100,000 deaths annually around the world. Poor treatment outcomes result from therapeutic failures and the fungi’s resistance to existing drugs.

A new multi-institutional study led by researchers at Michigan State University has characterized how fungi adapt to restructure their cell walls, effectively thwarting current antifungal medications. This new information opens opportunities to devise more effective use of antifungal drugs. The results were published July 31 in the journal Nature Communications.

“In order to improve the use of and develop new antifungal drugs, we need to understand the target,” said Tuo Wang, the inaugural Carl H. Brubaker Jr. Endowed Associate Professor in the Department of Chemistry at Michigan State University and lead author on the study. “This is not done easily, because the cell wall is very complex.”

The study was also selected to be featured among the journal's Editors' Highlights as one of the 50 best papers Nature Communications has published recently in the area of Microbiology and Infectious Diseases.

With this work, Wang and his team believe they have laid the foundation for pharmaceutical companies to adapt or combine existing antifungal drugs to help overcome their previous limitations.

Wang and his team believe they have laid the foundation for pharmaceutical companies to adapt or combine existing antifungal drugs to help overcome their previous limitations.

Cellular remodeling

Antifungal drugs target molecules in the fungal cell wall, a flexible, but rigid outer layer that provides the cell protection. By rupturing the protective structure, the drugs kill the fungal cell to control the fungal infection.

One of the newest families of antifungal drugs, echinocandins, target essential building blocks in the cell wall known as b-glucans. This attack should be effective, but fungi are extraordinary organisms that have evolved survival strategies to rebuild and reinforce the wall’s architecture.

In their new report, Wang and his colleagues determined the atom-by-atom configuration of the cell wall after exposure to echinocandins. To do this, they used biochemical analysis and state-of-the art imaging techniques, including solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance, dynamic nuclear polarization, transmission electron microscope and atomic force microscopy.

They then shared the results with a team at the MSU-Department of Energy Plant Research Laboratory, or PRL. The PRL team developed molecular dynamic simulations to illustrate nanoscale changes that unfold over hours to days in the fungal cell wall.

“NMR tells us that things are reacting but there is no picture,” said Josh Vermaas, assistant professor in the PRL. He’s also affiliated with the MSU Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology and the Molecular Plant Sciences Program.

Vermaas is a co-author on the study, who, together with Daipayan Sarkar, a research associate in the PRL, conducted the simulations portion of the study.

“We created visually appealing pictures of how molecules come together at the nanoscale, simulating the molecular details that we otherwise wouldn’t get access to,” Vermaas said.

The team found that when exposed to echinocandin, the fungi enhance their survival odds by making specific changes to the structure and organization of the components in their cell walls. In particular, as the concentration of b-glucans goes down, fungi rapidly increase the presence of different, but related molecules to regenerate and preserve the integrity of the cell wall.

In addition, polysaccharide structures, such as galactomannan and galactosaminogalactan, are reshuffled to enhance the stiffness and hydrophobic nature of the polymer network in the membrane.

“We found the supramolecular assembly has been fully reshuffled,” said Wang. “This dynamic dance unfolds both at the chemical and nanoscale levels, rendering the cell wall sturdier yet pliable, ensuring survival under stress.”

Not only did the fungal response to the drug increase the strength and resilience of the cell wall, the new architecture also eliminates the drug target in many instances. This renders the drugs ineffective against fungal spread.

“Biology is wild,” said Vermaas. “Evolutionary pressure allowed for these kinds of mechanisms to develop, but holy moly. How did fungi figure this out?”

Fungal spores are ubiquitous in the environment, but a healthy person’s immune system can sweep the spores from the body. People with compromised immune systems, however, are susceptible to the spores taking hold. That means, for example, people undergoing cancer treatments, receiving organ transplants or fighting other diseases, including AIDS and COVID, will have a harder time clearing the intruders.

In the body, fungi become established in the lungs and send long, branching structures called hyphae deep into lung tissue. Although drugs or surgery can alleviate an infection, once it’s in place, it is almost impossible to eliminate.

Only four families of an antifungal drugs are currently on the market, each limited by the evolutionary fungal roadblocks, such as the one identified in this study. That’s why the availability of effective antifungal drugs is needed now more than ever, Wang said

“We are doing the fundamental science,” said Wang. “Now that we understand how fungi survive antifungal treatment, this knowledge will be helpful for the development of new drugs.”

Also contributing to the study were Isha Gautam and Shi-You Ding at MSU; Frederic Mentink-Vigier at the National High Magnetic Field Laboratory; Andrew Lipton at the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, Thierry Fontaine at Paris Cité University; Jean-Paul Latgé at the University of Crete and Ping Wang at Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center.

END

How fungi elude antifungal treatments

2024-08-07

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

ACC Asia 2024 explores emerging trends, evidence-based strategies for improving global heart health

2024-08-07

The American College of Cardiology (ACC) and the Cardiological Society of India will host ACC Asia 2024 on August 16-18 in Delhi, India. This conference will bring together all members of the cardiac care team to examine emerging trends and best practices for cardiovascular disease patient care.

“One of the most meaningful outcomes of the annual ACC Asia conference is the ability to communicate with other cardiologists to strategize and innovate new ideas,” said Eugene Yang, MD, MS, FACC, one of the ACC Asia conference co-chairs. “As ...

CalTech team develops first noninvasive method to continually measure true blood pressure

2024-08-07

Solving a decades-old problem, a multidisciplinary team of Caltech researchers has figured out a method to noninvasively and continually measure blood pressure anywhere on the body with next to no disruption to the patient. A device based on the new technique holds the promise to enable better vital-sign monitoring at home, in hospitals, and possibly even in remote locations where resources are limited.

The new patented technique, called resonance sonomanometry, uses sound waves to gently stimulate resonance ...

Using photos or videos, these AI systems can conjure simulations that train robots to function in physical spaces

2024-08-07

Researchers working on large artificial intelligence models like ChatGPT have vast swaths of internet text, photos and videos to train systems. But roboticists training physical machines face barriers: Robot data is expensive, and because there aren’t fleets of robots roaming the world at large, there simply isn’t enough data easily available to make them perform well in dynamic environments, such as people’s homes.

Some researchers have turned to simulations to train robots. Yet even that process, which often involves a graphic designer ...

When is too much knowledge a bad thing?

2024-08-07

CORNELL UNIVERSITY MEDIA RELATIONS OFFICE

FOR RELEASE: August 7, 2024

Kaitlyn Serrao

607-882-1140

kms465@cornell.edu

When is too much knowledge a bad thing?

ITHACA, N.Y. – A new study finds an increase in knowledge could be a bad thing when people use it to act in their own self-interest rather than in the best interests of the larger group.

Cornell University economics professor Kaushik Basu and Jörgen Weibull, professor emeritus at the Stockholm School of Economics, are co-authors ...

Do smells prime our gut to fight off infection?

2024-08-07

Many organisms react to the smell of deadly pathogens by reflexively avoiding them. But a recent study from the University of California, Berkeley, shows that the nematode C. elegans also reacts to the odor of pathogenic bacteria by preparing its intestinal cells to withstand a potential onslaught.

As with humans, nematodes’ guts are a common target of disease-causing bacteria. The nematode reacts by destroying iron-containing organelles called mitochondria, which produce a cell's energy, to protect this critical element from iron-stealing bacteria. Iron is a key catalyst in many enzymatic reactions in cells — in particular, ...

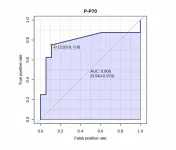

mTORC1 in classical monocytes: Links to human size variation & neuropsychiatric disease

2024-08-07

"This report suggests that a simple assay may allow cost-effective prediction of medication response."

BUFFALO, NY- August 7, 2024 – A new research paper was published in Aging (listed by MEDLINE/PubMed as "Aging (Albany NY)" and "Aging-US" by Web of Science), Volume 16, Issue 14 on July 26, 2024, entitled, “mTORC1 activation in presumed classical monocytes: observed correlation with human size variation and neuropsychiatric disease.”

In this new study, researchers Karl Berner, Naci Oz, Alaattin Kaya, Animesh Acharjee, and Jon Berner ...

In Parkinson’s, dementia may occur less often, or later, than thought

2024-08-07

MINNEAPOLIS – There’s some good news for people with Parkinson’s disease: The risk of developing dementia may be lower than previously thought, or dementia may occur later in the course of the disease than previously reported, according to a study published in the August 7, 2024, online issue of Neurology®, the medical journal of the American Academy of Neurology.

“The development of dementia is feared by people with Parkinson’s, and the combination of both a movement disorder and a cognitive disorder can be devastating to them and their loved ones,” said study author Daniel Weintraub, MD, ...

Impact of drought on drinking water contamination: disparities affecting Latino/a communities

2024-08-07

Long-term exposure to contaminants such as arsenic and nitrate in water is linked to an increased risk of various diseases, including cancers, cardiovascular diseases, developmental disorders and birth defects in infants. In the United States, there is a striking disparity in exposure to contaminants in tap water provided by community water systems (CWSs), with historically marginalized communities at greater risks compared to other populations. Often, CWSs that distribute water with higher contamination levels exist in areas that lack adequate public infrastructure or sociopolitical and financial resources.

In ...

Pesticide exposure linked to stillbirth risk in new study

2024-08-07

Living less than about one-third of a mile from pesticide use prior to conception and during early pregnancy could increase the risk of stillbirths, according to new research led by researchers at the Mel and Enid Zuckerman College of Public Health and Southwest Environmental Health Sciences Center.

Researchers found that during a 90-day pre-conception window and the first trimester of pregnancy, select pesticides, including organophosphates as a class, were associated with stillbirth.

The paper, “Pre-Conception ...

Individuals vary in how air pollution impacts their mood

2024-08-07

Affective sensitivity to air pollution (ASAP) describes the extent to which affect, or mood, fluctuates in accordance with daily changes in air pollution, which can vary between individuals, according to a study published August 7, 2024 in the open-access journal PLOS ONE by Michelle Ng from Stanford University, USA, and colleagues.

Individuals’ sensitivity to climate hazards is a central component of their vulnerability to climate change. Building on known associations between air pollution exposure and ...