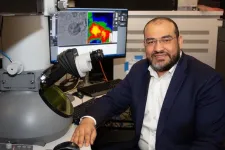

(Press-News.org) Imagine owning a camera so powerful it can take freeze-frame photographs of a moving electron – an object traveling so fast it could circle the Earth many times in a matter of a second. Researchers at the University of Arizona have developed the world's fastest electron microscope that can do just that.

They believe their work will lead to groundbreaking advancements in physics, chemistry, bioengineering, materials sciences and more.

"When you get the latest version of a smartphone, it comes with a better camera," said Mohammed Hassan, associate professor of physics and optical sciences. "This transmission electron microscope is like a very powerful camera in the latest version of smart phones; it allows us to take pictures of things we were not able to see before – like electrons. With this microscope, we hope the scientific community can understand the quantum physics behind how an electron behaves and how an electron moves."

Hassan led a team of researchers in the departments of physics and optical sciences that published the research article "Attosecond electron microscopy and diffraction" in the Science Advances journal. Hassan worked alongside Nikolay Golubev, assistant professor of physics; Dandan Hui, co-lead author and former research associate in optics and physics who now works at the Xi'an Institute of Optics and Precision Mechanics, Chinese Academy of Sciences; Husain Alqattan, co-lead author, U of A alumnus and assistant professor of physics at Kuwait University; and Mohamed Sennary, a graduate student studying optics and physics.

A transmission electron microscope is a tool used by scientists and researchers to magnify objects up to millions of times their actual size in order to see details too small for a traditional light microscope to detect. Instead of using visible light, a transmission electron microscope directs beams of electrons through whatever sample is being studied. The interaction between the electrons and the sample is captured by lenses and detected by a camera sensor in order to generate detailed images of the sample.

Ultrafast electron microscopes using these principles were first developed in the 2000's and use a laser to generate pulsed beams of electrons. This technique greatly increases a microscope's temporal resolution – its ability to measure and observe changes in a sample over time. In these ultrafast microscopes, instead of relying on the speed of a camera's shutter to dictate image quality, the resolution of a transmission electron microscope is determined by the duration of electron pulses.

The faster the pulse, the better the image.

Ultrafast electron microscopes previously operated by emitting a train of electron pulses at speeds of a few attoseconds. An attosecond is one quintillionth of a second. Pulses at these speeds create a series of images, like frames in a movie – but scientists were still missing the reactions and changes in an electron that takes place in between those frames as it evolves in real time. In order to see an electron frozen in place, U of A researchers, for the first time, generated a single attosecond electron pulse, which is as fast as electrons moves, thereby enhancing the microscope's temporal resolution, like a high-speed camera capturing movements that would otherwise be invisible.

Hassan and his colleagues based their work on the Nobel Prize-winning accomplishments of Pierre Agostini, Ferenc Krausz and Anne L’Huilliere, who won the Novel Prize in Physics in 2023 after generating the first extreme ultraviolet radiation pulse so short it could be measured in attoseconds.

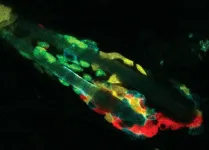

Using that work as a steppingstone, U of A researchers developed a microscope in which a powerful laser is split and converted into two parts – a very fast electron pulse and two ultra-short light pulses. The first light pulse, known as the pump pulse, feeds energy into a sample and causes electrons to move or undergo other rapid changes. The second light pulse, also called the "optical gating pulse" acts like a gate by creating a brief window of time in which the gated, single attosecond electron pulse is generated. The speed of the gating pulse therefore dictates the resolution of the image. By carefully synchronizing the two pulses, researchers control when the electron pulses probe the sample to observe ultrafast processes at the atomic level.

"The improvement of the temporal resolution inside of electron microscopes has been long anticipated and the focus of many research groups – because we all want to see the electron motion," Hassan said. "These movements happen in attoseconds. But now, for the first time, we are able to attain attosecond temporal resolution with our electron transmission microscope – and we coined it 'attomicroscopy.' For the first time, we can see pieces of the electron in motion."

END

Freeze-frame: U of A researchers develop world's fastest microscope that can see electrons in motion

2024-08-21

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

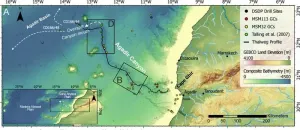

Study finds highest prediction of sea-level rise unlikely

2024-08-21

In recent years, the news about Earth's climate—from raging wildfires and stronger hurricanes, to devastating floods and searing heat waves—has provided little good news.

A new Dartmouth-led study, however, reports that one of the very worst projections of how high the world's oceans might rise as the planet's polar ice sheets melt is highly unlikely—though it stresses that the accelerating loss of ice from Greenland and Antarctica is nonetheless dire.

The study challenges a new and alarming prediction in the latest high-profile report from the United Nations' Intergovernmental Panel on ...

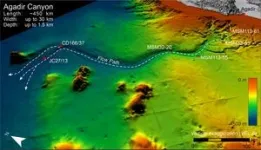

New study reveals devastating power and colossal extent of a giant underwater avalanche off the Moroccan coast

2024-08-21

New research by the University of Liverpool has revealed how an underwater avalanche grew more than 100 times in size causing a huge trail of destruction as it travelled 2000km across the Atlantic Ocean seafloor off the North West coast of Africa.

In a study publishing in the journal Science Advances (and featured on the front cover), researchers provide an unprecedented insight into the scale, force and impact of one of nature’s mysterious phenomena, underwater avalanches.

Dr Chris Stevenson, a sedimentologist from the University of Liverpool’s School of Environmental Sciences, co-led the team that for the first time has mapped a giant underwater avalanche from head ...

To kill mammoths in the Ice Age, people used planted pikes, not throwing spears, researchers say

2024-08-21

How did early humans use sharpened rocks to bring down megafauna 13,000 years ago? Did they throw spears tipped with carefully crafted, razor-sharp rocks called Clovis points? Did they surround and jab mammoths and mastadons? Or did they scavenge wounded animals, using Clovis points as a versatile tool to harvest meat and bones for food and supplies?

UC Berkeley archaeologists say the answer might be none of the above.

Instead, researchers say humans may have braced the butt of their pointed spears against the ground and angled the weapon upward in a way that would impale a charging animal. The force would have driven the spear deeper ...

Using AI to link heat waves to global warming

2024-08-21

Researchers at Stanford and Colorado State University have developed a rapid, low-cost approach for studying how individual extreme weather events have been affected by global warming. Their method, detailed in a Aug. 21 study in Science Advances, uses machine learning to determine how much global warming has contributed to heat waves in the U.S. and elsewhere in recent years. The approach proved highly accurate and could change how scientists study and predict the impact of climate change on a range of extreme weather events. The ...

The role of an energy-producing enzyme in treating Parkinson’s disease

2024-08-21

An enzyme called PGK1 has an unexpectedly critical role in the production of chemical energy in brain cells, according to a preclinical study led by researchers at Weill Cornell Medicine. The investigators found that boosting its activity may help the brain resist the energy deficits that can lead to Parkinson’s disease.

The study, published Aug. 21 in Science Advances, presented evidence that PGK1 is a “rate-limiting” enzyme in energy production in the output-signaling branches, or axons, of the dopamine neurons that are affected in Parkinson’s disease. This means that even a modest boost to PGK1 activity can have ...

Life from a drop of rain: New research suggests rainwater helped form the first protocell walls

2024-08-21

One of the major unanswered questions about the origin of life is how droplets of RNA floating around the primordial soup turned into the membrane-protected packets of life we call cells.

A new paper by engineers from the University of Chicago’s Pritzker School of Molecular Engineering (UChicago PME), the University of Houston’s Chemical Engineering Department, and biologists from the UChicago Chemistry Department, have proposed a solution.

In the paper, published today in Science Advances, UChicago PME postdoctoral researcher Aman Agrawal and his co-authors ...

Surprising mechanism for removing dead cells identified

2024-08-21

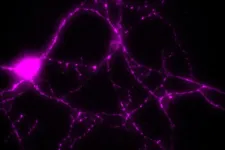

Billions of our cells die every day to make way for the growth of new ones. Most of these goners are cleaned up by phagocytes—mobile immune cells that migrate where needed to engulf problematic substances. But some dying or dead cells are consumed by their own neighbors, natural tissue cells with other primary jobs. How these cells sense the dying or dead around them has been largely unknown.

Now researchers from The Rockefeller University have shown how the sensor system operates in hair follicles, which have a well-known cycle of birth, decay, and regeneration put into motion by hair follicle stem cells (HFSCs). In a new study published in Nature, ...

UC Irvine discovery of ‘item memory’ brain cells offers new Alzheimer’s treatment target

2024-08-21

Irvine, Calif., Aug. 21, 2024 — Researchers from the University of California, Irvine have discovered the neurons responsible for “item memory,” deepening our understanding of how the brain stores and retrieves the details of “what” happened and offering a new target for treating Alzheimer’s disease.

Memories include three types of details: spatial, temporal and item, the “where, when and what” of an event. Their creation is a complex process that involves storing information based on the meanings and outcomes of different experiences and forms the foundation of our ability to recall and recount them.

The study, published ...

Study shows successful use of ChatGPT in ag education

2024-08-21

By John Lovett

University of Arkansas System Division of Agriculture

FAYETTEVILLE, Ark. — Artificial intelligence tools such as ChatGPT show promise as a useful means in agriculture to write simple computer programs for microcontrollers, according to a study published this month.

Microcontrollers are small computers that can perform tasks based on custom computer programs. They receive inputs from sensors and can be used in climate and irrigation controls, food processing systems, as well as robotic and drone applications, to name a few agricultural uses.

A recent study published with the Arkansas Agricultural ...

Early interventions may improve long-term academic achievement in young childhood brain tumor survivors

2024-08-21

(MEMPHIS, Tenn. – August 20, 2024) Children who survive a brain tumor often experience effects from both the cancer and its treatment long after therapy concludes. Scientists at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital found very young children treated for brain tumors were less prepared for school (represented by lower academic readiness scores) compared to their peers. This gap persisted once survivors entered formal schooling. Children from families of higher socioeconomic status were partially protected from the effect, suggesting that providing early developmental resources may proactively help reduce the academic achievement gap. The findings were published today in ...