Strength training activates cellular waste disposal

University of Bonn study: regulated degradation of damaged cell components prevents heart failure and nerve diseases

2024-08-23

(Press-News.org)

The elimination of damaged cell components is essential for the maintenance of the body’s tissues and organs. An international research team led by the University of Bonn has made significant findings on mechanisms for the clearing of cellular wastes, showing that strength training activates such mechanisms. The findings could form the basis for new therapies for heart failure and nerve diseases, and even afford benefits for manned space missions. A corresponding article has been published in the latest issue of the journal Current Biology. EMBARGOED: Do not publish until 5 pm CEST on August, 23rd!

Muscles and nerves are long-lasting, high-performance organs whose cellular components are subject to constant wear and tear. The protein BAG3 plays a critical role in the elimination of damaged components, identifying these and ensuring that they are enclosed by cellular membranes to form an “autophagosome”. Autophagosomes are like a garbage bag in which cellular waste is collected for later shredding and recycling. The research team led by Professor Jörg Höhfeld of the University of Bonn Institute of Cell Biology has shown that strength training activates BAG3 in the muscles. This has important ramifications for cellular waste disposal because BAG3 has to be activated to efficiently bind damaged cell components and promote membrane envelopment. An active elimination or clearing system is essential for the long-term preservation of muscle tissues. “Impairment of the BAG3 system does indeed cause swiftly progressing muscle weakness in children as well as heart failure—one of the most common causes of death in industrialized Western nations,” Professor Höhfeld explains.

Important implications for sports training and physical therapy

The study was conducted with significant involvement by sports physiologists of German Sport University Cologne and the University of Hildesheim. Professor Sebastian Gehlert of Hildesheim emphasizes how important the findings are: “We now know what intensity level of strength training it takes to activate the BAG3 system, so we can optimize training programs for top athletes and help physical therapy patients build muscle better.” Professor Gehlert also makes use of these findings to support members of the German Olympic team.

Necessary for the muscles ... and more

The BAG3 system is not only active in the muscles. Mutations in BAG3 can lead to a nerve disease known as Charcot-Marie-Tooth syndrome (named after the discovering scientist). The disease cause nerve fibers in the arms and legs to die off, leaving the individual unable to move his or her hands or feet. By studying cells from sufferers, the research team has now shown that certain manifestations of the syndrome cause faulty regulation of BAG3 elimination processes. The findings demonstrate the far-reaching significance of this system for tissue preservation.

Unexpected regulation pointing the way to new therapies

In analyzing BAG3 activation more closely, the researchers were surprised at what they observed. “Many cell proteins are activated by the attachment of phosphate groups in a process known as phosphorylation. With BAG3, however, the process is reversed,” explains Professor Jörg Höhfeld, also a member of the Transdisciplinary Research Area (TRA) Life and Health at the University of Bonn, “BAG3 is phosphorylated in resting muscles, and the phosphate groups are removed during activation.” At this point, phosphatases become the main focus of interest—the enzymes that remove the phosphate groups. To identify the phosphatases that activate BAG3, Höhfeld is collaborating with chemist and cell biologist Professor Maja Köhn of the University of Freiburg. “Identifying the phosphatases involved is a key step,” she relates, “so we can pursue the development of substances potentially able to influence BAG3 activation in the body." The research may open up new therapeutic possibilities for muscle weakness, heart failure and nerve diseases.

Relevant for space travel

Work on the BAG3 system is supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (German Research Foundation) through a research unit headed by Prof. Höhfeld. In addition, Höhfeld receives funds from the German Space Agency as the research is of interest for purposes of manned space missions. Professor Höhfeld points out: “BAG3 is activated under mechanical force. But what happens if mechanical stimulation does not take place? In astronauts living in a weightless environment, for example, or immobilized intensive care patients on ventilation?” In such cases, the lack of mechanical stimulation rapidly leads to muscle atrophy, the cause of which Höhfeld ascribes at least in part to the non-activation of BAG3. Drugs developed to activate BAG3 might help in such situations, he believes, which is why Höhfeld’s team is preparing experiments to be conducted on board of the International Space Station (ISS). BAG3 research thus could in fact help us reach Mars someday.

Institutions involved and funding secured

The University of Bonn’s partners in this study are the University of Freiburg, German Sport University, Forschungszentrum Jülich, the University of Antwerp and the University of Hildesheim. The work is co-funded by the German Research Foundation and the German Space Agency, part of the German Aerospace Center.

END

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2024-08-23

Exploring new energy storage and conversion technologies is crucial for sustainable human development. Proton exchange membrane fuel cells (PEMFCs) and metal-air batteries are particularly promising due to their high energy efficiency and environmental friendliness. A key component in these technologies is the oxygen reduction reaction (ORR) catalyst. Traditionally, ORR catalysts rely on expensive platinum group metals (PGM), which are cost-prohibitive for widespread use. This has spurred interest in developing non-precious metal alternatives, such as transition metal/nitrogen-doped carbon-based materials (M–N–C). Among these, Fe–N–C ...

2024-08-23

This study is led by Prof. Shunxin Wang (State Key Laboratory of Reproductive Medicine and Offspring Health, Center for Reproductive Medicine, Institute of Women, Children and Reproductive Health, Shandong University) and Prof. Liangran Zhang (Advanced Medical Research Institute, Shandong University). In their study of meiosis in budding yeast, the research team found that yeast senses temperature changes by increasing the level of DNA negative supercoils to increase crossovers and modulate chromosome organization ...

2024-08-23

Individual cells divide through a process called mitosis, during which the cell’s copied DNA is separated between two resulting daughter cells. Despite recent advances in cell biology, the mechanism by which DNA condenses during mitosis is still poorly understood. Researchers recently tracked small stretches of DNA wound around histone proteins, called nucleosomes, to better characterize nucleosome behavior during cell division.

DNA is organized as chromatin, which are dynamic structures comprised of DNA, RNA, and proteins that regulate the accessibility of genes for expression and the overall configuration of genetic material in the cell. Histone proteins, for example, are positively ...

2024-08-23

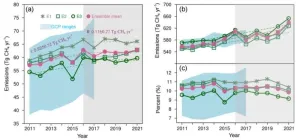

Methane is a potent greenhouse gas. Since the Industrial Revolution, atmospheric methane concentrations have nearly doubled, with its radiative forcing accounting for one-third of all greenhouse gases. As one of the world's largest methane emitters, China made a clear commitment as early as 2007 to "strive to control the growth rate of methane emissions." The country's 12th, 13th, and 14th Five-Year Plans all proposed measures to control methane emissions. In 2023, China released the "Methane Emission Control Action ...

2024-08-23

The income and education levels of a child’s environment determine their relationship to nature, not whether they live in a city or the countryside. This is the finding of a new study conducted by researchers at Lund University, Sweden. The results run counter to the assumption that growing up in the countryside automatically increases our connection to nature, and yet the study also shows that nature close to home increases children’s well-being.

There is a general concern that, with urbanisation, people have lost contact with nature. According to research, less contact ...

2024-08-23

An international study led by Institute of Natural Resources and Agrobiology of Seville (IRNAS-CSIC), of the Spanish National Research Council (CISC), has shown that as the number of global change factors increases, terrestrial ecosystems become more sensitive to the impacts of global change. The results, published in the prestigious journal Nature Geoscience, show that the resistance of our ecosystems to global change decreases significantly as the number of environmental stressors increases, especially when this stress is sustained over time.

This is the conclusion reached by the Biodiversity and Ecosystem Functioning ...

2024-08-23

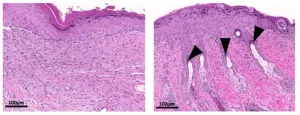

Researchers at Rutgers University in New Jersey have discovered that a protein produced by parasitic worms in the gut enhances wound healing in mice. The study, to be published August 23 in the journal Life Science Alliance (LSA), reveals that applying the protein to skin wounds speeds up wound closure, improves skin regeneration, and inhibits the formation of scar tissue. Whether the protein can be harnessed to enhance wound healing in human patients remains to be seen.

Skin wounds must be rapidly closed in order to prevent infection, but rapid wound closure can favor the development of scar tissue instead of properly regenerated skin. The balance between scarring ...

2024-08-23

In a recent comprehensive review published in Cyborg Bionic Systems, researchers led by Keyi Li from the General Hospital of Northern Theater Command in Shenyang, along with international collaborators, detail significant advances in the identification and application of biomarkers for prostate cancer (PCa). This critical insight is pivotal as prostate cancer remains one of the most common malignancies among men globally, emphasizing the urgent need for effective diagnostic and therapeutic strategies.

Prostate cancer is characterized by a multitude of molecular aberrations that complicate its early ...

2024-08-23

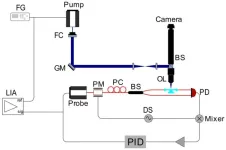

A team of researchers led by Professor Sebastian Deindl at Uppsala University has developed a pioneering method that vastly improves the ability to observe and analyse complex biological processes at the single-molecule level. Their work is set to be published in the upcoming issue of the journal Science.

“With our new technique, we can now extend single-molecule biophysics to the genome scale. This advance is expected to significantly deepen our understanding of how nucleic-acid interacting proteins function in ...

2024-08-23

The detection of individual particles and molecules has opened new horizons in analytical chemistry, cellular imaging, nanomaterials, and biomedical diagnostics. Traditional single-molecule detection methods rely heavily on fluorescence techniques, which require labeling of the target molecules. In contrast, photothermal microscopy has emerged as a promising label-free, non-invasive imaging technique. This method measures localized variations in the refractive index of a sample's surroundings, resulting from light absorption by sample components, which induces temperature changes in the surrounding region. Whispering ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Strength training activates cellular waste disposal

University of Bonn study: regulated degradation of damaged cell components prevents heart failure and nerve diseases