(Press-News.org) Climate scientists have long agreed that humans are largely responsible for climate change. A new study, co-led by Bojana Većkalov from the University of Amsterdam and Sandra Geiger from the University of Vienna, finds that communicating the scientific consensus about climate change can clear up misperceptions and strengthen beliefs about the existence and the causes of climate change. The team surveyed over 10,000 people from 27 countries on 6 continents. The study has just been published in the renowned journal Nature Human Behaviour.

Scientific consensus identifying humans as primarily responsible for climate change is not new and was already forming in the 1980s. Today, 97% to 99.9% of climate scientists agree that climate change is happening and that human activity is the primary cause. Over the past decade, researchers have begun to study the effects of communicating this overwhelming consensus – with promising results. So far, however, such studies have primarily been conducted in the United States. "As is the case with many findings in behavioral science, we know little about the effects of communicating this consensus beyond the United States. Our study now takes an extensive and detailed look at these effects," says environmental psychologist Sandra Geiger from the University of Vienna.

The international research team of 46 collaborators showed different scientific consensus messages to more than 10,500 people and subsequently asked them about their opinions on climate change. "We observed that previous findings from the United States hold true in other parts of the world as well," explains co-lead author Bojana Većkalov from the University of Amsterdam. Across all 27 countries, people responded similarly to the scientific consensus on the existence and causes of climate change. Co-lead author Geiger further explains: "Prior to reading about the consensus among climate scientists, people estimated this consensus to be much lower than it really is. In response to reading about it, they adjusted their own perceptions, believed more in climate change, and worried more about it – but they did not support public action on climate change more."

88% of climate scientists additionally agree that climate change constitutes a crisis. How do people react when they learn about this additional crisis consensus? Interestingly, this added piece of information did not have any effects. Co-lead author Većkalov explains: "We believe that the gap between the actual and perceived consensus could have played a role. When it came to consensus on the existence and causes of climate change, respondents thought the scientific consensus was lower than it actually was, adjusted their estimate, and revised their beliefs. In the case of the crisis consensus, the respondents’ estimate was substantially closer to the actual consensus, and this gap was likely not big enough to alter beliefs about climate change."

These new findings show that it is important to continue emphasizing the consensus among climate scientists – be it in the media or in our everyday lives when we have conversations about climate change and its impacts. "Especially in the face of increasing politicization of science and misinformation about climate change, cultivating universal awareness of the scientific consensus will help protect public understanding of the issue", adds senior author Sander van der Linden from the University of Cambridge. "Beyond climate change communication, these findings also underscore the importance of testing previous findings in behavioral science globally. Such endeavors are only possible if we bring together researchers worldwide", summarizes study co-lead Sandra Geiger.

Besides Sandra Geiger, Mathew White and Jakob Götz from the University of Vienna were also involved in this study. What is particularly unique about this work is the involvement of students and early-career researchers from the Junior Researcher Programme (JRP) and the Global Behavioral Science (GLOBES) program at Columbia University.

END

Scientific consensus can strengthen pro-climate attitudes in society

A new study clearly shows how important it is to emphasize consensus among climate scientists

2024-08-26

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

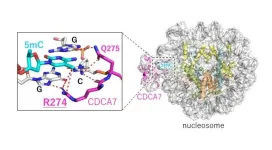

Unraveling the role of CDCA7 in maintenance of DNA methylation

2024-08-26

DNA methylation, a process by which methyl groups are added to DNA molecules, is essential for the maintenance of DNA and the overall health of an organism. Disruptions in the standard DNA methylation patterns can lead to immunodeficiency and diseases such as cancer. Helicase lymphoid-specific (HELLS) is an enzyme that facilitates DNA methylation by remodeling the nucleosome - the tightly packed structure of DNA wound around histone proteins. The absence of HELLS or its activator, cell division cycle associated 7 (CDCA7) is known to be a factor that leads to the disruption of DNA methylation. Mutations in the genes that code for HELLS and CDCA7 cause rare disorder immunodeficiency, ...

Study finds salamanders are surprisingly abundant in northeastern forests

2024-08-26

RESTON, Va. — Two recent amphibian-focused studies shed light on the ecological importance of red-backed salamanders, while confirming that proactive measures would prevent costly impacts from a wildlife disease spreading across Europe that has not yet reached North America.

Scientists knew that red-backed salamanders were abundant in eastern North America, but a recent study found their densities and biomass across the region were much higher than expected. The study authors estimated an average of ...

Old chemo drug, new pancreatic cancer therapy?

2024-08-26

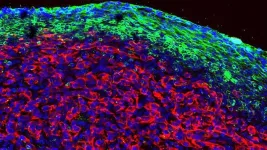

The fight against cancer is an arms race, and one of the most effective weapons in clinicians’ arsenals is immunotherapy. Immune checkpoint therapy has become the standard for treating several types of cancer. However, the Nobel Prize-winning strategy is ineffective for most pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) patients.

“Immune checkpoint therapy is only an option in rare cases of PDAC,” Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) Professor Douglas Fearon says. “It’s only effective for patients with a specific subtype of PDAC—that’s less than 5% of all cases.”

Until recently, it was thought that PDAC didn’t ...

Shakespeare in sign language, seen through AI

2024-08-26

A new study uses co-creation with reference communities to develop an app for sign language machine translation (SLMT). The research team designed a theatrical performance in sign language, seen through the eyes of artificial intelligence (AI), as one of the methodologies. “Historically, deaf people have been excluded from the development of automatic translation technologies,” says Shaun O’Boyle, Research Fellow in the School of Inclusive and Special Education (Dublin City University DCU). “This has often caused backlash and resistance from deaf communities, as the projects were designed and ...

PLOS and the University of South Carolina announce APC-free Open Access publishing agreement

2024-08-26

SAN FRANCISCO — The University of South Carolina and the Public Library of Science (PLOS) today announced a three-year Open Access agreement that allows researchers to publish in PLOS journals[1] without incurring article processing charges (APC). This partnership brings together two organizations that believe researchers should be able to access content freely and make their work available publicly, regardless of their access to funds.

“The evidence is undeniable — open research enables the convergence of ...

Why children can’t pay attention to the task at hand

2024-08-26

COLUMBUS, Ohio – Scientists have learned that children find it hard to focus on a task, and often take in information that won’t help them complete their assignment. But the question is, why?

In a new study, researchers found that this “distributed attention” wasn’t because children’s brains weren’t mature enough to understand the task or pay attention, and it wasn’t because they were easily distracted and lacked the control to focus.

It now appears that kids distribute their attention broadly either out of simple curiosity or because their working memory isn’t developed enough to complete a task without “over ...

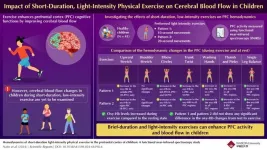

Short-duration, light-intensity exercises improve cerebral blood flow in children

2024-08-26

Cognitive functions, also known as intellectual functions, encompass thinking, understanding, memory, language, computation, and judgment, and are performed in the cerebrum. The prefrontal cortex (PFC), located in the frontal lobe of the cerebral cortex, handles these functions. Studies have shown that exercise improves cognitive function through mechanisms such as enhanced cerebral blood flow, structural changes in the brain, and promotion of neurogenesis. However, 81% of children globally do not engage in enough physical activity, leading to high levels of sedentary behavior and insufficient exercise. This lack of physical ...

Exploring the role of cytochrome oxygenases in augmenting austocystin D-mediated cytotoxicity

2024-08-26

Austocystin D, a natural compound produced by fungi, has been recognized for its cytotoxic effects and anticancer activity in various cell types. It exhibits potent activity even in cells that express proteins associated with multidrug resistance, attracting significant global research interest. Austocystin D promotes cell death by damaging their DNA, a process which might be dependent on cytochrome P450 (CYP) oxygenase enzymes. Notably, austocystin D has shown significant activity against cancer cells with increased CYP expression. However, the specific role and function of the CYP2J2 enzyme in the cytotoxicity of austocystin D remain ...

Knowing you have a brain aneurysm may raise anxiety risk, other mental health conditions

2024-08-26

Research Highlights:

People diagnosed with unruptured cerebral aneurysms (weakened areas in brain blood vessels) who are being monitored without treatment have a higher risk of developing mental illness compared to those who have not been diagnosed with a cerebral aneurysm. The largest impact was among adults younger than age 40.

The study conducted in South Korea found that the psychological burden caused by the diagnosis of an unruptured aneurysm may contribute to the development of mental health conditions, such as anxiety, stress, depression, eating ...

Non-cognitive skills: the hidden key to academic success

2024-08-26

A new Nature Human Behaviour study, jointly led by Dr Margherita Malanchini at Queen Mary University of London and Dr Andrea Allegrini at University College London, has revealed that non-cognitive skills, such as motivation and self-regulation, are as important as intelligence in determining academic success. These skills become increasingly influential throughout a child's education, with genetic factors playing a significant role. The research, conducted in collaboration with an international team of experts, suggests that fostering non-cognitive skills alongside cognitive abilities could significantly improve educational ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Differing immune responses in infants may explain increased severity of RSV over SARS-CoV-2

The invisible hand of climate change: How extreme heat dictates who is born

Surprising culprit leads to chronic rejection of transplanted lungs, hearts

Study explains how ketogenic diets prevent seizures

New approach to qualifying nuclear reactor components rolling out this year

U.S. medical care is improving, but cost and health differ depending on disease

AI challenges lithography and provides solutions

Can AI make society less selfish?

UC Irvine researchers expose critical security vulnerability in autonomous drones

Changes in smoking status and their associations with risk of Parkinson’s, death

In football players with repeated head impacts, inflammation related to brain changes

Being an early bird, getting more physical activity linked to lower risk of ALS

The Lancet: Single daily pill shows promise as replacement for complex, multi-tablet HIV treatment regimens

Single daily pill shows promise as replacement for complex, multi-tablet HIV treatment regimens

Black Americans face increasingly higher risk of gun homicide death than White Americans

Flagging claims about cancer treatment on social media as potentially false might help reduce spreading of misinformation, per online experiment with 1,051 US adults

Yawns in healthy fetuses might indicate mild distress

Conservation agriculture, including no-dig, crop-rotation and mulching methods, reduces water runoff and soil loss and boosts crop yield by as much as 122%, in Ethiopian trial

Tropical flowers are blooming weeks later than they used to through climate change

Risk of whale entanglement in fishing gear tied to size of cool-water habitat

Climate change could fragment habitat for monarch butterflies, disrupting mass migration

Neurosurgeons are really good at removing brain tumors, and they’re about to get even better

Almost 1-in-3 American adolescents has diabetes or prediabetes, with waist-to-height ratio the strongest independent predictor of prediabetes/diabetes, reveals survey of 1,998 adolescents (10-19 years

Researchers sharpen understanding of how the body responds to energy demands from exercise

New “lock-and-key” chemistry

Benzodiazepine use declines across the U.S., led by reductions in older adults

How recycled sewage could make the moon or Mars suitable for growing crops

Don’t Panic: ‘Humanity’s Last Exam’ has begun

A robust new telecom qubit in silicon

Vertebrate paleontology has a numbers problem. Computer vision can help

[Press-News.org] Scientific consensus can strengthen pro-climate attitudes in societyA new study clearly shows how important it is to emphasize consensus among climate scientists