(Press-News.org) LA JOLLA, CA—Fighting cancer effectively often involves stopping cancer cells from multiplying, which requires understanding proteins that the cells rely on to survive. Protein profiling plays a critical role in this process by helping researchers identify proteins—and their specific parts—that future drugs should target. But when used on their own, past approaches haven’t been detailed enough to spotlight all potential protein targets, leading to some being missed.

Now, by combining two methods of protein analysis, a team of chemists at Scripps Research has mapped more than 300 small molecule-reactive cancer proteins, as well as their small molecule binding sites. Revealing key protein targets that, when disrupted with certain chemical compounds (or small molecules), halt cancer cell growth may eventually enable the development of more effective and precise cancer treatments. The findings were published in Nature Chemistry on August 13, 2024.

“One method gave us a broad view of which proteins were interacting with the chemicals, and the second method showed exactly where those interactions were happening,” says co-senior author Benjamin Cravatt, PhD, the Norton B. Gilula Chair in Biology and Chemistry at Scripps Research.

Both methods are forms of activity-based protein profiling (ABPP), a technique that Cravatt pioneered to capture protein activity on a global scale. The research team used their dual approach to flag both the proteins and protein sites that interacted with a library of stereoprobes—chemical compounds designed to permanently bind to proteins in a selective manner. Stereoprobes are used to study protein functions and identify possible drug targets.

“We made a conscious effort to design our stereoprobes with chemical features that tend to be underrepresented in compounds typically used in drug discovery settings,” says co-senior author Bruno Melillo, PhD, an institute investigator in the Department of Chemistry at Scripps Research. “This strategy increases our chances of making discoveries that can advance biology, and eventually translate into improvements to human health.”

The research team’s stereoprobes were electrophilic, meaning they were designed to irreversibly bind to proteins—specifically to cysteine. This amino acid is pervasive in proteins, including those found in cancer cells, and it helps form important structural bonds. When chemicals react with cysteine, they can disrupt these bonds and cause proteins to malfunction, which interferes with cell growth, and many cancer drugs irreversibly bind to cysteines on proteins.

“We also focused on cysteine because it’s the most nucleophilic amino acid,” says first author Evert Njomen, PhD, an HHMI Hanna H. Gray Fellow at Scripps Research and a postdoctoral research associate in Cravatt’s lab.

To find out which specific proteins would bond with the stereoprobes, the team turned to a method known as protein-directed ABPP. Using this approach, the researchers uncovered more than 300 individual proteins that reacted with the stereoprobe compounds. But still, they wanted to dig deeper and identify the reactions’ precise locations.

The second method, called cysteine-directed ABPP, pinpointed exactly where the stereoprobes were binding on the proteins. This allowed the team to “zoom in” on a specific protein pocket and examine whether the cysteine within reacted with the stereoprobes, similar to focusing on a single spot on a puzzle board to see if a particular piece fits.

Each stereoprobe molecule had two main components: the binding part and the electrophilic part. Once the binding component recognizes the cancer cell protein pocket, hopefully, the stereoprobe molecule can enter—like how a key needs to fit in a lock. When a stereoprobe remained in a pocket that’s critical to the cancer cell’s function, it blocked the protein from binding to other proteins—ultimately preventing cell division.

“By targeting these very specific stages in the cell cycle, there’s potential to slow down the growth of cancer cells,” says Njomen. “A cancer cell would stay in what is almost a state of two cells, and your body’s immune system would detect it as defective and direct it to die.”

Identifying precise protein regions that are critical to cancer cell survival could help researchers develop more targeted treatments to stop cells from multiplying.

Among the team’s other key findings was confirming that their double-pronged approach painted a more accurate picture of protein-stereoprobe reactivity than a single method.

“We've always known that both methods had their drawbacks, but we didn’t know exactly how much information was lost by using just one technique,” says Njomen. “It was surprising to see that a substantial number of protein targets were missed when we used one platform over the other.”

The team hopes that their findings will one day inform new cancer therapies targeting cell division. In the meantime, Njomen wants to design new stereoprobe libraries to uncover protein pockets implicated in illnesses beyond cancer, including inflammatory disorders.

“Many proteins have been implicated in diseases, but we don't have stereoprobes to research them,” she said. “Moving forward, I’d like to find more protein pockets that we can study for drug discovery purposes.”

In addition to Cravatt, Njomen and co-senior author Bruno Melillo, authors of the study, “Multi-Tiered Chemical Proteomic Maps of Tryptoline Acrylamide-Protein Interactions in Cancer Cells” are Rachel E. Hayward, Kristen E. DeMeester, Daisuke Ogasawara and Melissa M. Dix of Scripps Research; Tracey Nguyen, Paige Ashby and Gabriel M. Simon of Vividion Therapeutics; and Stuart L. Schreiber of the Broad Institute.

This work and the researchers involved were supported by funding from the National Institutes of Health (U19 AI142784 and R35 CA231991); Cancer Research UK (CGCATF-2021/100012 and CGCATF-2021/100021) the National Cancer Institute (OT2CA278688 and OT2CA278692); the Howard Hughes Medical Institute Hanna H. Gray Fellowship (NGT15176), the Jane Coffin Childs Memorial Fellowship, and Vividion Therapeutics.

//

About Scripps Research

Scripps Research is an independent, nonprofit biomedical institute ranked one of the most influential in the world for its impact on innovation by Nature Index. We are advancing human health through profound discoveries that address pressing medical concerns around the globe. Our drug discovery and development division, Calibr-Skaggs, works hand-in-hand with scientists across disciplines to bring new medicines to patients as quickly and efficiently as possible, while teams at Scripps Research Translational Institute harness genomics, digital medicine and cutting-edge informatics to understand individual health and render more effective healthcare. Scripps Research also trains the next generation of leading scientists at our Skaggs Graduate School, consistently named among the top 10 US programs for chemistry and biological sciences. Learn more at www.scripps.edu.

END

New way to potentially slow cancer growth

Using a combination of two protein-mapping methods, Scripps Research scientists uncover novel proteins that could be targeted by future cancer drugs

2024-08-26

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Using machine learning to speed up simulations of irregularly shaped particles

2024-08-26

Simulating particles is a relatively simple task when those particles are spherical. In the real world, however, most particles are not perfect spheres but take on irregular and varying shapes and sizes. Simulating these particles becomes a much more challenging and time-consuming task.

The ability to simulate particles is critical to understanding how they behave. For example, microplastics are a new form of pollution as plastic waste has increased drastically and uncontrollably decays in the environment ...

Ochsner Digital Medicine teams up with AmeriHealth Caritas Louisiana to improve treatment of hypertension, Type 2 diabetes

2024-08-26

New Orleans, LA. – Ochsner Digital Medicine has teamed up with AmeriHealth Caritas Louisiana to offer digital medicine services to the health plan’s members. Utilizing remote patient management (RPM), Ochsner Digital Medicine and AmeriHealth Caritas Louisiana will work together to help members with certain chronic conditions better manage their health and improve their quality of life.

AmeriHealth Caritas Louisiana, part of the AmeriHealth Caritas Family of Companies, is a Healthy Louisiana managed Medicaid health plan covering ...

Closing the RNA loop holds promise for more stable, effective RNA therapies

2024-08-26

New methods to shape RNA molecules into circles could lead to more effective and long-lasting therapies, shows a study by researchers at the University of California San Diego. The advance holds promise for a range of diseases, offering a more enduring alternative to existing RNA therapies, which often suffer from short-lived effectiveness in the body.

The work was published Aug. 26 in Nature Biomedical Engineering.

RNA molecules have emerged as powerful tools in modern medicine. They can silence ...

Controlling molecular electronics with rigid, ladder-like molecules

2024-08-26

As electronic devices continue to get smaller and smaller, physical size limitations are beginning to disrupt the trend of doubling transistor density on silicon-based microchips approximately every two years according to Moore’s law. Molecular electronics—the use of single molecules as the building blocks for electronic components—offers a potential pathway for the continued miniaturization of small-scale electronic devices. Devices that utilize molecular electronics require precise control over the flow of electrical current. However, the dynamic nature of these single molecule components affects device performance and impacts ...

Marine science oxygen produced in the deep sea raises questions about extraterrestrial life

2024-08-26

Over 12,000 feet below the surface of the sea, in a region of the Pacific Ocean known as the Clarion-Clipperton Zone (CCZ), million-year-old rocks cover the seafloor. These rocks may seem lifeless, but nestled between the nooks and crannies on their surfaces, tiny sea creatures and microbes make their home, many uniquely adapted to life in the dark.

These deep-sea rocks, called polymetallic nodules, don’t only host a surprising number of sea critters. A team of scientists that includes Boston University experts has discovered they ...

What microscopic fossilized shells tell us about ancient climate change

2024-08-26

At the end of the Paleocene and beginning of the Eocene epochs, between 59 to 51 million years ago, Earth experienced dramatic warming periods, both gradual periods stretching millions of years and sudden warming events known as hyperthermals.

Driving this planetary heat up were massive emissions of carbon dioxide (CO2) and other greenhouse gases, but other factors like tectonic activity may have also been at play.

New research led by University of Utah geoscientists pairs sea surface temperatures with levels ...

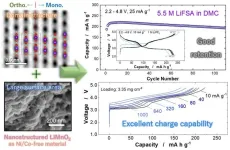

Li-ion batteries show promise as cheap and sustainable alternative to Ni/Co materials

2024-08-26

Lithium-ion (or Li-ion) batteries are heavy hitters when it comes to the world of rechargeable batteries. As electric vehicles become more common in the world, a high-energy, low-cost battery utilizing the abundance of manganese (Mn) can be a sustainable option to become commercially available and utilized in the automobile industry. Currently, batteries used for powering electric vehicles (EVs) are nickel (Ni) and cobalt (Co)-based, which can be expensive and unsustainable for a society with a growing desire for EVs. By switching the positive electrode ...

The Lundquist Institute announces updates to its Board of Directors

2024-08-26

The Lundquist Institute for Biomedical Innovation at Harbor-UCLA Medical Center (TLI) announced updates to its Board of Directors today. TLI welcomes one new distinguished member and thanks the two outgoing members for their invaluable contributions.

“On behalf of the Board, I am delighted that Dr. Bill Dorfman, a global leader in cosmetic dentistry, has joined the TLI Board. Dr. Dorfman's extensive expertise and commitment to philanthropy make him an invaluable addition to our leadership,” said Mitchel Sayare, PhD, TLI Board ...

Research from UTHealth Houston finds parents who recently experienced intimate partner violence had higher potential for parenting stress and child maltreatment

2024-08-26

Parents who recently experienced intimate partner violence reported more parenting stress and higher potential for child maltreatment, and were less likely to use positive parenting strategies, according to UTHealth Houston research published Aug. 26, 2024, in JAMA Pediatrics.

“Our findings demonstrate the collateral damage of domestic violence — that the negative consequences are not limited to the couple and instead have the potential to affect how they parent, and ultimately the health of their children. We must expend every effort to prevent this public health problem,” said Jeff Temple, PhD, ...

Research spotlight: Key regulators of pd-1 in melanoma cells and the immune system’s response

2024-08-26

How would you summarize your study for a lay audience?

Immune checkpoint inhibitors are cancer fighting drugs that help the immune system do its job of detecting and attacking tumor cells. Programmed Cell Death 1 (PD-1) is a common target for this type of drug—it is a protein that sits on the surface of T cells and helps regulate the immune system’s response to neighboring cells, both normal and cancerous. While most research efforts to date have focused on PD-1’s role in T cells, it is also active in many other kinds of cells—including cancer cells as first demonstrated by the Schatton ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Pathway to residency program helps kids and the pediatrician shortage

How the color of a theater affects sound perception

Ensuring smartphones have not been tampered with

Overdiagnosis of papillary thyroid cancer

Association of dual eligibility and medicare type with quality of postacute care after stroke

Shine a light, build a crystal

AI-powered platform accelerates discovery of new mRNA delivery materials

Quantum effect could power the next generation of battery-free devices

New research finds heart health benefits in combining mango and avocado daily

New research finds peanut butter consumption builds muscle power in older adults

Study identifies aging-associated mitochondrial circular RNAs

The brain’s primitive ‘fear center’ is actually a sophisticated mediator

Brain Healthy Campus Collaborative announces winner of first-ever Brain Health Prize

Tokyo Bay’s night lights reveal hidden boundaries between species

As worms and jellyfish wriggle, new AI tools track their neurons

ATG14 identified as a central guardian against liver injury and fibrosis

Research identifies blind spots in AI medical triage

$9M for exploring the fundamental limits of entangled quantum sensor networks

Study shows marine plastic pollution alters octopus predator-prey encounters

Night lights can structure ecosystems

A parasitic origin for the ribosome?

A gold-standard survey of the American mood

Tool for identifying children at risk of speech disorders

How Japanese medical trainees view artificial intelligence in medicine

MambaAlign fusion framework for detecting defects missed by inspection systems

Children born with upper limb difference show the incredible adaptability of the young brain

How bacteria can reclaim lost energy, nutrients, and clean water from wastewater

Fast-paced lives demand faster vision: ecology shapes how “quickly” animals see time

Global warming and heat stress risk close in on the Tour de France

New technology reveals hidden DNA scaffolding built before life ‘switches on’

[Press-News.org] New way to potentially slow cancer growthUsing a combination of two protein-mapping methods, Scripps Research scientists uncover novel proteins that could be targeted by future cancer drugs