(Press-News.org)

Collagen, a protein found in bones and connective tissue, has been found in dinosaur fossils as old as 195 million years. That far exceeds the normal half-life of the peptide bonds that hold proteins together, which is about 500 years.

A new study from MIT offers an explanation for how collagen can survive for so much longer than expected. The research team found that a special atomic-level interaction defends collagen from attack by water molecules. This barricade prevents water from breaking the peptide bonds through a process called hydrolysis.

“We provide evidence that that interaction prevents water from attacking the peptide bonds and cleaving them. That just flies in the face of what happens with a normal peptide bond, which has a half-life of only 500 years,” says Ron Raines, the Firmenich Professor of Chemistry at MIT.

Raines is the senior author of the new study, which will appear in ACS Central Science. MIT postdoc Jinyi Yang PhD ’24 is the lead author of the paper. MIT postdoc Volga Kojasoy and graduate student Gerard Porter are also authors of the study.

Water-resistant

Collagen is the most abundant protein in animals, and it is found in not only bones but also skin, muscles, and ligaments. It’s made from long strands of protein that intertwine to form a tough triple helix.

“Collagen is the scaffold that holds us together,” Raines says. “What makes the collagen protein so stable, and such a good choice for this scaffold, is that unlike most proteins, it’s fibrous.”

In the past decade, paleobiologists have found evidence of collagen preserved in dinosaur fossils, including an 80-million-year-old Tyrannosaurus rex fossil, and a sauropodomorph fossil that is nearly 200 million years old.

Over the past 25 years, Raines’ lab has been studying collagen and how its structure enables its function. In the new study, they revealed why the peptide bonds that hold collagen together are so resistant to being broken down by water.

Peptide bonds are formed between a carbon atom from one amino acid and a nitrogen atom of the adjacent amino acid. The carbon atom also forms a double bond with an oxygen atom, forming a molecular structure called a carbonyl group. This carbonyl oxygen has a pair of electrons that don’t form bonds with any other atoms. Those electrons, the researchers found, can be shared with the carbonyl group of a neighboring peptide bond.

Because this pair of electrons is being inserted into those peptide bonds, water molecules can’t also get into the structure to disrupt the bond.

To demonstrate this, Raines and his colleagues created two interconverting mimics of collagen — the one that usually forms a triple helix, which is known as trans, and another in which the angles of the peptide bonds are rotated into a different form, known as cis. They found that the trans form of collagen did not allow water to attack and hydrolyze the bond. In the cis form, water got in and the bonds were broken.

“A peptide bond is either cis or trans, and we can change the cis to trans ratio. By doing that, we can mimic the natural state of collagen or create an unprotected peptide bond. And we saw that when it was unprotected, it was not long for the world,” Raines says.

“No weak link”

This sharing of electrons has also been seen in protein structures known as alpha helices, which are found in many proteins. These helices may also be protected from water, but the helices are always connected by protein sequences that are more exposed, which are still susceptible to hydrolysis.

“Collagen is all triple helices, from one end to the other,” Raines says. “There’s no weak link, and that’s why I think it has survived.”

Previously, some scientists have suggested other explanations for why collagen might be preserved for millions of years, including the possibility that the bones were so dehydrated that no water could reach the peptide bonds.

“I can’t discount the contributions from other factors, but 200 million years is a long time, and I think you need something at the molecular level, at the atomic level in order to explain it,” Raines says.

The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health and the National Science Foundation.

###

Written by Anne Trafton, MIT News

Paper: “Pauli Exclusion by n→π* Interactions: Implications for Paleobiology”

END

Feeld, the dating app for the curious, in collaboration with Dr. Justin Lehmiller of The Kinsey Institute, has released a groundbreaking report, "The State of Dating: How Gen Z is Redefining Sexuality and Relationships." Released on World Sexual Health Day under the theme #PositiveRelationships, this report takes a deep dive into how Gen Z—shaped by global instability, digital immersion, and evolving cultural scripts—are shaping their approach to dating and sexuality.

After analyzing ...

Seattle, WA and New York, NY—September 4, 2024—Today, the Allen Institute for Cell Science and New York Stem Cell Foundation (NYSCF) announced a pioneering collaboration to address this critical issue, combining two cutting-edge technologies to create more inclusive cellular models for studying disease. This partnership will introduce the Allen Institute for Cell Science’s structure tags into NYSCF’s collection of ethnically diverse stem cell lines. The result: an unprecedented resource that will enable researchers to examine disease mechanisms and potential treatments across a ...

Photosynthesis can take place in nature even at extremely low light levels. This is the result of an international study that investigated the development of Arctic microalgae at the end of the polar night. The measurements were carried out as part of the MOSAiC expedition at 88° northern latitude and revealed that even this far north, microalgae can build up biomass through photosynthesis as early as the end of March. At this time, the sun is barely above the horizon, so that it is still almost completely dark in the microalgae's habitat under the snow and ice cover of the Arctic Ocean. The results of the study now published in the journal Nature Communications show that photosynthesis ...

New research shows that parasitic nematodes, responsible for infecting more than a billion people globally, carry viruses that may solve the puzzle of why some cause serious diseases.

A study led by Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine (LSTM) used cutting-edge bioinformatic data mining techniques to identify 91 RNA viruses in 28 species of parasitic nematodes, representing 70% of those that infect people and animals. Often these are symptomless or not serious, but some can lead to severe, ...

A new study led by Portuguese paleontologist Pedro Mocho, from the Instituto Dom Luiz of the Faculty of Sciences of the University of Lisbon (CIÊNCIAS), has just been published in the Communications Biology journal, which announces a new species of sauropod dinosaur that lived in Cuenca, Spain, 75 million years ago: Qunkasaura pintiquiniestra.

The more than 12,000 fossils collected from 2007 onwards during works to install the Madrid-Levante high-speed train (AVE) tracks revealed this deposit, giving rise to one of the most relevant collections ...

Sports-related concussions (SRC) may not be associated with long-term cognitive risks for non-professional athletes, a study led by a UNSW medical researcher suggests. In fact, study participants who had experienced an SRC had better cognitive performance in some areas than those who had never suffered a concussion, pointing to potential protective effects of sports participation.

Published in the Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry (JNNP), the research reveals that individuals who reported experiencing any SRC during their lifetime had a marginally better cognitive performance than those who reported no concussions.

The study, a collaboration ...

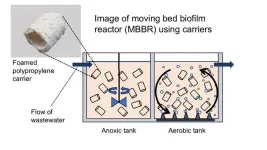

For the sake of the environment and our quality of life, effective treatment of wastewater plays a vital role. A biological method to treat sewage using moving, biofilm-covered plastic items known as carriers has been gaining prominence, and an Osaka Metropolitan University-led team has found ways to make the process more efficient.

The moving bed biofilm reactor (MBBR) process purifies wastewater by putting these carriers in motion to get the biofilm’s microorganisms into greater contact with organic matter and other impurities. The more biofilm that can be attached ...

A common image of cats today comes in the form of cute cat memes online, but these furry felines commonly experience kidney disease. Amid advances in medicine to improve people’s quality of life, an Osaka Metropolitan University-led team has, for the first time in the world, generated high-quality feline induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), which have the potential to help companion animals and humans alike.

Human iPSCs have been generated using just four genes known as transcription factors, but feline iPSCs have been difficult to generate. Graduate School of Veterinary Science Professor Shingo Hatoya led the team in introducing six transcription factors via the Sendai virus ...

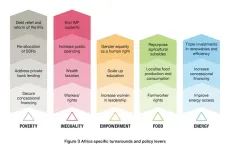

In the best-case scenario, called the "Giant Leap," Sub-Saharan Africa could see poverty drop from 500 million to 25 million people, hunger nearly eradicated, and universal access to education, clean water, and sustainable electricity. On the other hand, the "Too Little Too Late" scenario paints a grim picture where poverty rises to 900 million, hunger still affects 180 million, and over a billion people lack clean water. The Too Little Too Late scenario is based on existing policies in the region. These two scenarios highlight the critical importance of action this decade to drive five extraordinary turnarounds in the areas of poverty, inequality, ...

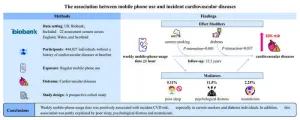

Philadelphia, September 4, 2024 – A new study has found that regular mobile phone use was positively associated with incident cardiovascular diseases risk, especially in current smokers and individuals with diabetes. In addition, this association was partly attributed to poor sleep, psychological distress, and neuroticism. The article in the Canadian Journal of Cardiology, published by Elsevier, details the results of this large-scale prospective cohort study.

Yanjun Zhang, MD, Division of Nephrology, Nanfang Hospital, Southern Medical University, Guangzhou, China, explains, "Mobile phone use is a ubiquitous exposure in modern society, so exploring its impact on health has ...