(Press-News.org) Media Contact: laura.kurtzman@ucsf.edu, (415) 502-6397

Subscribe to UCSF News

After a spinal cord injury, nearby cells quickly rush to action, forming protective scar tissue around the damaged area to stabilize and protect it. But over time, too much scarring can prevent nerves from regenerating, impeding the healing process and leading to permanent nerve damage, loss of sensation or paralysis.

Now, UC San Francisco researchers have discovered how a rarely studied cell type controls the formation of scar tissue in spinal cord injuries. Activating a molecular pathway within these cells, the team showed in mice, lets them control levels of spinal cord scarring. The new research appears Sept. 18 in Nature.

“By illuminating the basic signaling biology behind spinal cord scarring, these findings raise the possibility of one day being able to pharmacologically fine-tune the extent of that scarring,” said David Julius, PhD, the senior author of the new paper, professor and chair of physiology at UCSF, and winner of the 2021 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.

Spinal cord injuries — caused by physical trauma such as vehicle accidents, falls, or sports collisions — can damage the nerves that run down the length of the spinal cord and coordinate messages between the brain and the rest of the body. Treatments largely revolve around surgery or braces to stabilize the spine, drugs to control pain and swelling and physical therapy.

Julius and his colleagues were studying the function of a poorly understood group of neurons, called cerebrospinal fluid (CSF)-contacting neurons. These neurons are found along the hollow channel that runs through the center of the cord, and they extend into the spinal fluid that fills the channel.

An opioid that modulates scarring

The team developed a new method to label these neurons, isolate them and measure which genes were active in the cells. That led them to discover that the cells express a receptor that senses κ-opioids, which are naturally produced by the human body.

The group went on to identify the spinal cord cells that produce κ-opioids, and show how the molecules excite the CSF-contacting neurons.

Further experiments revealed that signaling through these κ-opioids decreased in the aftermath of a spinal cord injury, transforming nearby cells into scar tissue for protection.

The researchers tried delivering extra κ-opioids to the mice, and the scarring was reduced; but the spinal cord injuries were more severe, and the mice did not recover their motor coordination as well.

“κ-opioids might give us a way, after a spinal cord injury, to pharmacologically modulate the fine balance between producing enough scar tissue and having excessive scarring,” said Wendy Yue, PhD, a former postdoctoral research fellow in Julius’ lab who is now an assistant professor of physiology at UCSF and the first author of the new paper.

Importantly, κ-opioids are different from commercial opioid drugs such as oxycodone and hydrocodone, and generally not addictive.

Scientists must do more work to understand why κ-opioid levels drop after spinal cord injuries, as well as what the ideal levels of scarring are to support optimal healing. Further preclinical studies also would be required before testing κ-opioid-related drugs in humans with spinal cord injuries.

Julius said the new findings underscore the importance of carrying out basic scientific research on how various cell types and signaling molecules work.

“We were not looking for a way to control spinal cord healing,” he said. “This came out of asking questions about this mysterious cell type, and then running into a mechanism that is both biologically interesting and could eventually have some therapeutic potential.”

Authors: The other authors were Kouki Touhara, Kenichi Toma, and Xin Duan of UCSF.

Funding: The work was supported by a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Hanna Gray Fellowship, a Croucher Fellowship for Postdoctoral Research, a Damon Runyon Cancer Research Foundation Fellowship (DRG-2387-30), a New Frontier Research Award from the UCSF Program for Breakthrough Biomedical Research, and the National Institutes of Health (R01EY030138, R35 NS105038).

About UCSF: The University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) is exclusively focused on the health sciences and is dedicated to promoting health worldwide through advanced biomedical research, graduate-level education in the life sciences and health professions, and excellence in patient care. UCSF Health, which serves as UCSF's primary academic medical center, includes top-ranked specialty hospitals and other clinical programs, and has affiliations throughout the Bay Area. UCSF School of Medicine also has a regional campus in Fresno. Learn more at ucsf.edu, or see our Fact Sheet.

###

Follow UCSF

ucsf.edu | Facebook.com/ucsf | YouTube.com/ucsf

END

Research points a way to modulate scarring in spinal cord injury

UCSF scientists have discovered a new molecular pathway that controls the formation of scar tissue in spinal cord injuries. In the future, it could be targeted by drugs to promote healing.

2024-09-18

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Breast and ovarian cancer newly linked to thousands of gene variants

2024-09-18

Scientists have pinpointed thousands of genetic changes in a gene that may increase a person’s risk of developing breast and ovarian cancer, paving the way for better risk assessment and more personalised care.

Researchers from the Wellcome Sanger Institute and their collaborators focused on the ‘cancer protection’ gene RAD51C, finding over 3,000 harmful genetic changes that could potentially disrupt its function and increase ovarian cancer risk six-fold and risk of aggressive subtypes of breast ...

Metal exposure can increase cardiovascular disease risk

2024-09-18

Metal exposure from environmental pollution is associated with increased calcium buildup in the coronary arteries at a level comparable to traditional risk factors like smoking and diabetes, according to a study published today in JACC, the flagship journal of the American College of Cardiology. The findings support that metals in the body are associated with the progression of plaque buildup in the arteries and potentially provide a new strategy for managing and preventing atherosclerosis.

"Our findings highlight the importance ...

Penny for your thoughts? Master copper regulator discovery may offer Alzheimer’s clues

2024-09-18

New therapeutic opportunities often emerge from research on simple organisms. For instance, the 2020 Nobel Prize in Chemistry awarded to Emmanuelle Charpentier, Ph.D., and Jennifer Doudna, Ph.D., for their CRISPR-based DNA editing discovery began with studies using bacteria just a decade prior. Today, CRISPR therapies are approved for several disorders, and more such treatments are in the offing.

Recognizing the translational potential of studies in simpler animal models, a team of scientists led by Randy D. Blakely, ...

Keck Hospital of USC named a 2024 top performer by Vizient, Inc.

2024-09-18

LOS ANGELES — Keck Hospital of USC has been named a top performer in the 2024 Bernard A. Birnbaum, MD, Quality Leadership award by Vizient, Inc., a leading health care performance improvement company.

The top performer designation acknowledges the hospital’s excellence in delivering high-quality care as measured by the annual Vizient Quality and Accountability Study.

Keck Hospital was among 14 top performers out of 115 comprehensive academic medical centers nationally and achieved a five-star ...

NSF and Simons Foundation launch 2 AI Institutes to help astronomers understand the cosmos

2024-09-18

Note: Embargoed until 8:00 a.m. ET on Sept. 18, 2024

From the early telescopes made hundreds of years ago by Galileo to the sophisticated astronomical observatories of today, people have built increasingly innovative tools to probe and measure the cosmos. Soon, researchers at two new institutes funded by the U.S. National Science Foundation and the Simons Foundation will build a new breed of astronomical tools by harnessing the uniquely powerful abilities of artificial intelligence to assist and accelerate humanity's understanding of the universe.

The new National Artificial Intelligence ...

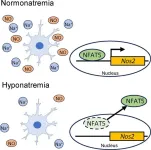

Exploring the effect of low sodium concentrations on brain microglial cells

2024-09-18

Low serum sodium concentrations in blood are called hyponatremia, a prevalent clinical electrolyte disorder. In contrast to acute hyponatremia, chronic hyponatremia has been previously considered asymptomatic because the brain can successfully adapt to hyponatremia. If not treated, chronic hyponatremia can lead to complications such as fractures, falls, memory impairment, and other mental issues. Treating the chronic condition is, however, quite tricky as it has been observed that overly rapid correction of hyponatremia ...

New Alzheimer’s studies reveal disease biology, risk for progression, and the potential for a novel blood test

2024-09-18

EMBARGOED by Alzheimer’s & Dementia until 7 a.m., ET, Sept. 18, 2024

Contact: Gina DiGravio, Boston University, 617-358-7838, ginad@bu.edu

Contact: Andrea Zeek, IU School of Medicine, 317-671-3114, anzeek@iu.edu

(Boston)— The failure to diagnose Alzheimer’s disease, the most common form of dementia in the elderly, at an early stage of molecular pathology is considered a major reason why treatments fail in clinical trials. Previous research to molecularly diagnose Alzheimer’s disease yielded "A/T/N" central biomarkers based on the measurements of proteins, β-amyloid (“A”) and tau (“T”), ...

Comorbidity and disease activity in multiple sclerosis

2024-09-18

About The Study: In this study, a higher burden of comorbidity was associated with worse clinical outcomes in people with multiple sclerosis (MS), although comorbidity could potentially be a partial mediator of other negative prognostic factors. The findings suggest a substantial adverse association of the comorbidities investigated with MS disease activity and that prevention and management of comorbidities should be a pressing concern in clinical practice.

Corresponding Author: To contact the corresponding author, Amber Salter, PhD, email amber.salter@utsouthwestern.edu.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this ...

£18 million for DARE UK to support secure research on sensitive data

2024-09-18

London, United Kingdom, 18 September 2024 – UK Research and Innovation (UKRI), the UK’s largest public funder of research, has confirmed funding for a new phase of the DARE UK (Data and Analytics Research Environments UK) programme with up to £18.2 million made available over 2.5 years.

Starting this month, Phase 2 of the DARE UK programme will bring together Trusted Research Environments (TREs) across the UK to test and build new capabilities for a connected national network of secure data ...

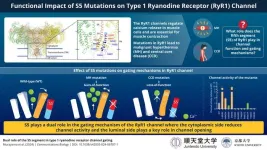

New study unveils the impact of mutations in the calcium release channel on muscle diseases

2024-09-18

The type 1 ryanodine receptor (RyR1) is an important calcium release channel in skeletal muscles essential for muscle contraction. It mediates calcium release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum, a calcium-storing organelle in muscle cells, a process vital for muscle function. Mutations in the RyR1 gene can affect the channel's function in extremely contrasting ways leading to severe muscle diseases such as malignant hyperthermia (MH) and central core disease (CCD). MH is an inherited disease that causes high fever and muscle contractures in response to inhalational anesthetics in patients with gain-of-function RyR1 variants. CCD is one ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Learning makes brain cells work together, not apart

Engineers improve infrared devices using century-old materials

Physicists mathematically create the first ‘ideal glass’

Microbe exposure may not protect against developing allergic disease

Forest damage in Europe to rise by around 20% by 2100 even if warming is limited to 2°C

Rapid population growth helped koala’s recovery from severe genetic bottleneck

CAR-expressing astrocytes target and clear amyloid-β in mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease

Unique Rubisco subunit boosts carbon assimilation in land plants

Climate change will drive increasing forest disturbances across Europe throughout the next century

Enhanced brain cells clear away dementia-related proteins

This odd little plant could help turbocharge crop yields

Flipped chromosomal segments drive natural selection

Whole-genome study of koalas transforms how we understand genetic risk in endangered species

Worcester Polytechnic Institute identifies new tool for predicting Alzheimer’s disease

HSS studies highlight advantages of osseointegration for people with an amputation

Buck Institute launches Healthspan Horizons to turn long-term health data into Actionable healthspan insights

University of Ottawa Heart Institute, the University of Ottawa and McGill University launch ARCHIMEDES to advance health research in Canada

The world’s largest brain research prize awarded for groundbreaking discoveries on how we sense touch and pain

Magnetofluids help to overcome challenges in left atrial appendage occlusion

Brain-clearing cells offer clues to slowing Alzheimer’s disease progression

mRNA therapy restores fertility in genetically infertile mice

Cloaked stem cells evade immune rejection in mice, pointing to a potential universal donor cell line

Growth in telemedicine has not improved mental health care access in rural areas, study finds

Pitt scientists engineer “living eye drop” to support corneal healing

Outcomes of older adults with advanced cancer who prefer quality of life vs prolonging survival

Lower music volume levels in fitness class and perceived exercise intensity

Of crocodiles, counting and conferences

AERA announces 2026 award winners in education research

Saving two lives with one fruit drop

Photonic chips advance real-time learning in spiking neural systems

[Press-News.org] Research points a way to modulate scarring in spinal cord injuryUCSF scientists have discovered a new molecular pathway that controls the formation of scar tissue in spinal cord injuries. In the future, it could be targeted by drugs to promote healing.