(Press-News.org)

Researchers have long observed that a common family of environmental bacteria, Comamonadacae, grow on plastics littered throughout urban rivers and wastewater systems. But what, exactly, these Comamonas bacteria are doing has remained a mystery.

Now, Northwestern University-led researchers have discovered how cells of a Comamonas bacterium are breaking down plastic for food. First, they chew the plastic into small pieces, called nanoplastics. Then, they secrete a specialized enzyme that breaks down the plastic even further. Finally, the bacteria use a ring of carbon atoms from the plastic as a food source, the researchers found.

The discovery opens new possibilities for developing bacteria-based engineering solutions to help clean up difficult-to-remove plastic waste, which pollutes drinking water and harms wildlife.

The study will be published on Thursday (Oct. 3) in the journal Environmental Science & Technology.

“We have systematically shown, for the first time, that a wastewater bacterium can take a starting plastic material, deteriorate it, fragment it, break it down and use it as a source of carbon,” said Northwestern’s Ludmilla Aristilde, who led the study. “It is amazing that this bacterium can perform that entire process, and we identified a key enzyme responsible for breaking down the plastic materials. This could be optimized and exploited to help get rid of plastics in the environment.”

An expert in the dynamics of organics in environmental processes, Aristilde is an associate professor of environmental engineering at Northwestern’s McCormick School of Engineering. She also is a member of the Center for Synthetic Biology, International Institute for Nanotechnology and Paula M. Trienens Institute for Sustainability and Energy. The study’s co-first authors are Rebecca Wilkes, a former Ph.D. student in Aristilde’s lab, and Nanqing Zhou, a current postdoctoral associate in Aristilde’s lab. Several former graduate and undergraduate researchers from the Aristilde Lab also contributed to the work.

The pollution problem

The new study builds on previous research from Aristilde’s team, which unraveled the mechanisms that enable Comamonas testosteri to metabolize simple carbons generated from broken down plants and plastics. In the new research, Aristilde and her team again looked to C. testosteroni, which grows on polyethylene terephthalate (PET), a type of plastic commonly used in food packaging and beverage bottles. Because it does not break down easily, PET is a major contributor to plastic pollution.

“It’s important to note that PET plastics represent 12% of total global plastics usage,” Aristilde said. “And it accounts for up to 50% of microplastics in wastewaters.”

Innate ability to degrade plastics

To better understand how C. testosteroni interacts with and feeds on the plastic, Aristilde and her team used multiple theoretical and experimental approaches. First, they took bacterium — isolated from wastewater — and grew it on PET films and pellets. Then, they used advanced microscopy to observe how the surface of the plastic material changed over time. Next, they examined the water around the bacteria, searching for evidence of plastic broken down into smaller nano-sized pieces. And, finally, the researchers looked inside the bacteria to pinpoint tools the bacteria used to help degrade the PET.

“In the presence of the bacterium, the microplastics were broken down into tiny nanoparticles of plastics,” Aristilde said. “We found that the wastewater bacterium has an innate ability to degrade plastic all the way down to monomers, small building blocks which join together to form polymers. These small units are a bioavailable source of carbon that bacteria can use for growth.”

After confirming that C. testosteroni, indeed, can break down plastics, Aristilde next wanted to learn how. Through omics techniques that can measure all enzymes inside the cell, her team discovered one specific enzyme the bacterium expressed when exposed to PET plastics. To further explore this enzyme’s role, Aristilde asked collaborators at Oak Ridge National Laboratory in Tennessee to prepare bacterial cells without the abilities to express the enzyme. Remarkably, without that enzyme, the bacteria’s ability to degrade plastic was lost or significantly diminished.

How plastics change in water

Although Aristilde imagines this discovery potentially could be harnessed for environmental solutions, she also says this new knowledge can help people better understand how plastics evolve in wastewater.

“Wastewater is a huge reservoir of microplastics and nanoplastics,” Aristilde said. “Most people think nanoplastics enter wastewater treatment plants as nanoplastics. But we’re showing that nanoplastics can be formed during wastewater treatment through microbial activity. That’s something we need to pay attention to as our society tries to understand the behavior of plastics throughout its journey from wastewater to receiving rivers and lakes.”

The study, “Mechanisms of polyethylene terephthalate pellet fragmentation into nanoplastics and assimilable carbons by wastewater Comamonas,” was supported by the National Science Foundation (award number CHE-2109097).

END

10-2-24

Contacts:

Sougata Roy, Mechanical Engineering, 515-294-5001, sroy@iastate.edu

Mike Krapfl, News Service, 515-294-4917, mkrapfl@iastate.edu

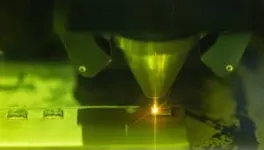

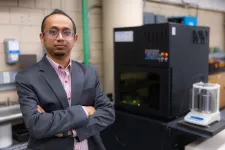

Researchers study 3D printing tungsten parts for extreme conditions in nuclear reactors

AMES, Iowa – Sougata Roy, who doesn’t study electrons or grids or wind turbines, has found a way to contribute to a clean-energy future.

“This work in advanced manufacturing, particularly in using additive manufacturing, is about making a difference,” ...

EMBARGOED: NOT FOR RELEASE UNTIL THURSDAY 3 OCTOBER AT 07:00 ET (12:00 UK TIME)

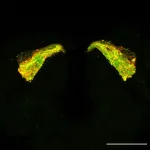

An international team of researchers have made a promising breakthrough in the development of drugs to treat Alzheimer’s Disease.

For the first time, scientists have developed a drug that works on both major aggregation-promoting ‘hotspots’ of the Tau protein - addressing a critical gap in current treatments.

The drug, a peptide inhibitor called RI-AG03, was effective at preventing the build-up of Tau proteins - a key driver of neurodegeneration - in both lab and fruit fly studies.

The ...

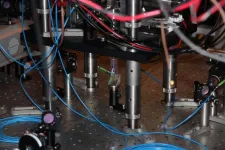

University of Copenhagen mathematicians have developed a recipe for upgrading quantum computers to simulate complex quantum systems, such as molecules. Their discovery brings us closer to being able to predict how new drugs will behave within our bodies and has the potential to revolutionize pharmaceutical development.

Developing a new drug can take more than a decade and cost anywhere from hundreds of millions to billions of euro — with multiple failed attempts along the way. But what if we could predict how a drug worked ...

A new publication in Nature Reviews Methods Primers provides essential guidance for conducting rigorous systematic reviews on studies with animals and cells. It also highlights the benefits of these reviews, such as improving reproducibility and reducing animal use, and addresses potential pitfalls and recent advancements like review automation.

Systematic reviews synthesize existing evidence in a scientific field to answer specific research questions in a structured and unbiased way. With over 100 million animals used in scientific ...

Oysters once formed extensive reefs along much of Europe's coastline – but these complex ecosystems were destroyed over a century ago, new research shows.

Based on documents from the 18th and 19th Centuries, the study reveals that European flat oysters formed large reefs of both living and dead shells, providing a habitat supporting rich biodiversity.

Today these oysters are mostly found as scattered individuals – but the researchers found evidence of reefs almost everywhere, from Norway to the Mediterranean, covering at least 1.7 million hectares, an area larger than Northern Ireland.

The research was ...

Utilizing one of the longest-running ecosystem experiments in the Arctic, a Colorado State University-led team of researchers have developed a better understanding of the interplay among plants, microbes and soil nutrients — findings that offer new insight into how critical carbon deposits may be released from thawing Arctic permafrost.

Estimates suggest that Arctic soils contain nearly twice the amount of carbon that is currently in the atmosphere. As climate change has caused portions of Earth’s northernmost polar regions to thaw, scientists have long been concerned about significant amounts of carbon being released in the ...

The legacy of the Soviet Union’s collapse plays a greater role in the foreign policies of Georgia and Ukraine than previous studies have suggested. Conducting foreign policy in former Soviet countries can be a major challenge as the Russian state does not accept the new order. These are the findings outlined in the thesis of political scientist Per Ekman from Uppsala University.

“To understand Russia’s war in Ukraine, for example, it is important to see the war as part of a longer historical event. Since their first day of independence, Georgia and Ukraine have had to deal with Russian ambitions to control the region. For many in the West, it took a ...

Oxford, UK – Genomic Press has released a captivating interview with Professor Robin Dunbar, the eminent evolutionary psychologist and anthropologist whose work has fundamentally altered our understanding of human social networks. Published in the Innovators and Ideas section of Genomic Psychiatry, this in-depth conversation offers unique insights into Professor Dunbar's scientific journey and the far-reaching implications of his research.

Professor Dunbar, best known for conceptualizing "Dunbar's number" - the cognitive limit to the number of stable social relationships ...

Hepatocellular carcinoma, a type of liver cancer associated with hepatitis infections, is known to have a high recurrence rate after cancer removal. Recent advances in antiviral therapy have reduced the number of patients affected, but obesity and diabetes are factors in hepatocellular carcinoma prevalence. However, these factors’ effects on patient survival and cancer recurrence have been unclear.

To gain insights, Dr. Hiroji Shinkawa’s research team at Osaka Metropolitan University’s Graduate School of Medicine analyzed the relationship between diabetes mellitus, obesity, and postoperative outcomes in 1,644 patients with hepatocellular carcinoma ...

Duke-NUS introduces 35 innovative pictograms to make medication instructions clearer, especially for seniors.

These visual aids are designed to ensure patients take their medications correctly and safely, with the aim of improving overall health outcomes.

The team looks to collaborate with healthcare institutions and pharmacies to standardise pictograms portraying medication instructions across Singapore.

SINGAPORE, 3 OCTOBER 2024 – Transforming patient care through clarity and simplicity, Duke-NUS Medical School has introduced visual aids or pictograms designed to make medication instructions clearer. ...