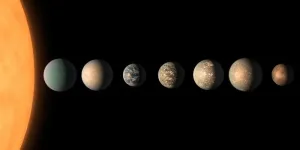

Many black holes detected to date appear to be part of a pair. These binary systems comprise a black hole and a secondary object — such as a star, a much denser neutron star, or another black hole — that spiral around each other, drawn together by the black hole’s gravity to form a tight orbital pair.

Now a surprising discovery is expanding the picture of black holes, the objects they can host, and the way they form.

In a study appearing in Nature, physicists at MIT and Caltech report that they have observed a “black hole triple” for the first time. The new system holds a central black hole in the act of consuming a small star that’s spiraling in very close to the black hole, every 6.5 days — a configuration similar to most binary systems. But surprisingly, a second star appears to also be circling the black hole, though at a much greater distance. The physicists estimate this far-off companion is orbiting the black hole every 70,000 years.

That the black hole seems to have a gravitational hold on an object so far away is raising questions about the origins of the black hole itself. Black holes are thought to form from the violent explosion of a dying star — a process known as a supernova, by which a star releases a huge amount of energy and light in a final burst before collapsing into an invisible black hole.

The team’s discovery, however, suggests that if the newly-observed black hole resulted from a typical supernova, the energy it would have released before it collapsed would have kicked away any loosely bound objects in its outskirts. The second, outer star, then, shouldn’t still be hanging around.

Instead, the team suspects the black hole formed through a more gentle process of “direct collapse,” in which a star simply caves in on itself, forming a black hole without a last dramatic flash. Such a gentle origin would hardly disturb any loosely bound, faraway objects.

Because the new triple system includes a very far-off star, this suggests the system’s black hole was born through a gentler, direct collapse. And while astronomers have observed more violent supernovae for centuries, the team says the new triple system could be the first evidence of a black hole that formed from this more gentle process.

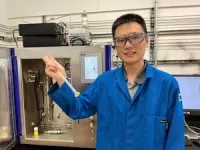

“We think most black holes form from violent explosions of stars, but this discovery helps call that into question,” says study author Kevin Burdge, a Pappalardo Fellow in the MIT Department of Physics. “This system is super exciting for black hole evolution, and it also raises questions of whether there are more triples out there.”

The study’s co-authors at MIT are Erin Kara, Claude Canizares, Deepto Chakrabarty, Anna Frebel, Sarah Millholland, Saul Rappaport, Rob Simcoe, and Andrew Vanderburg, along with Kareem El-Badry at Caltech.

Tandem motion

The discovery of the black hole triple came about almost by chance. The physicists found it while looking through Aladin Lite, a repository of astronomical observations, aggregated from telescopes in space and all around the world. Astronomers can use the online tool to search for images of the same part of the sky, taken by different telescopes that are tuned to various wavelengths of energy and light.

The team had been looking within the Milky Way galaxy for signs of new black holes. Out of curiosity, Burdge reviewed an image of V404 Cygni — a black hole about 8,000 light years from Earth that was one of the very first objects ever to be confirmed as a black hole, in 1992. Since then, V404 Cygni has become one of the most well-studied black holes, and has been documented in over 1,300 scientific papers. However, none of those studies reported what Burdge and his colleagues observed.

As he looked at optical images of V404 Cygni, Burdge saw what appeared to be two blobs of light, surprisingly close to each other. The first blob was what others determined to be the black hole and an inner, closely orbiting star. The star is so close that it is shedding some of its material onto the black hole, and giving off the light that Burdge could see. The second blob of light, however, was something that scientists did not investigate closely, until now. That second light, Burdge determined, was most likely coming from a very far-off star.

“The fact that we can see two separate stars over this much distance actually means that the stars have to be really very far apart,” says Burdge, who calculated that the outer star is 3,500 astronomical units (AU) away from the black hole (1 AU is the distance between the Earth and sun). In other words, the outer star is 3,500 times father away from the black hole as the Earth is from the sun. This is also equal to 100 times the distance between Pluto and the sun.

The question that then came to mind was whether the outer star was linked to the black hole and its inner star. To answer this, the researchers looked to Gaia, a satellite that has precisely tracked the motions of all the stars in the galaxy since 2014. The team analyzed the motions of the inner and outer stars over the last 10 years of Gaia data and found that the stars moved exactly in tandem, compared to other neighboring stars. They calculated that the odds of this kind of tandem motion are about one in 10 million.

“It’s almost certainly not a coincidence or accident,” Burdge says. “We’re seeing two stars that are following each other because they’re attached by this weak string of gravity. So this has to be a triple system.”

Pulling strings

How, then, could the system have formed? If the black hole arose from a typical supernova, the violent explosion would have kicked away the outer star long ago.

“Imagine you’re pulling a kite, and instead of a strong string, you’re pulling with a spider web,” Burdge says. “If you tugged too hard, the web would break and you’d lose the kite. Gravity is like this barely bound string that’s really weak, and if you do anything dramatic to the inner binary, you’re going to lose the outer star.”

To really test this idea, however, Burdge carried out simulations to see how such a triple system could have evolved and retained the outer star.

At the start of each simulation, he introduced three stars (the third being the black hole, before it became a black hole). He then ran tens of thousands of simulations, each one with a slightly different scenario for how the third star could have become a black hole, and subsequently affected the motions of the other two stars. For instance, he simulated a supernova, varying the amount and direction of energy that it gave off. He also simulated scenarios of direct collapse, in which the third star simply caved in on itself to form a black hole, without giving off any energy.

“The vast majority of simulations show that the easiest way to make this triple work is through direct collapse,” Burdge says.

In addition to giving clues to the black hole’s origins, the outer star has also revealed the system’s age. The physicists observed that the outer star happens to be in the process of becoming a red giant — a phase that occurs at the end of a star’s life. Based on this stellar transition, the team determined that the outer star is about 4 billion years old. Given that neighboring stars are born around the same time, the team concludes that the black hole triple is also 4 billion years old.

“We’ve never been able to do this before for an old black hole,” Burdge says. “Now we know V404 Cygni is part of a triple, it could have formed from direct collapse, and it formed about 4 billion years ago, thanks to this discovery.”

This work was supported, in part, by the National Science Foundation.

###

Written by Jennifer Chu, MIT News

END