(Press-News.org)

Imagine trying to settle into a new home while constantly being attacked. That’s what the bacterium Pseudomonas aeruginosa faces when it infects the lungs, and it can’t both spread and protect itself from antibiotics at the same time. Nonetheless, it’s one of the top culprits in hospital-acquired infections and it’s notorious for causing long-lasting, antibiotic-resistant infections, causing damage especially in people with lung diseases like cystic fibrosis, COPD, or bronchiectasis.

To survive tough conditions, P. aeruginosa forms colonies known as “biofilms” – clusters of bacteria encased in a self-produced matrix that provides them with significant advantages, including protection from antibiotics.

But biofilms come at a cost: the clustered bacteria also lose the ability to move around, find nutrients, and spread effectively. For P. aeruginosa infecting a lung, this poses a dilemma: should it spread across the lung’s surface or bunker down to resist incoming antibiotics? Achieving the right balance can mean life and death for the pathogen – and disrupting it can mean life or death for patients.

New research by the group of Alexandre Persat at EPFL’s Global Health Institute has now uncovered how P. aeruginosa manages the trade-off between colonizing and surviving during infection by switching between biofilm formation for antibiotic protection and a more mobile, “planktonic” state to spread and access nutrients, depending on the environmental pressures they face. The study is published in Nature Microbiology.

Mimicking natural infection environments to observe the bacteria

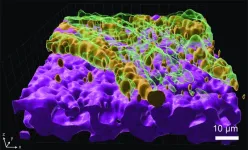

To better understand P. aeruginosa’s behavior, the researchers grew the bacteria on mucus-covered tissue models that mimic human lungs. These tissue models, known as “organoids”, are at the cutting-edge of bioengineering.

“We then used a high throughput screening technique called transposon-insertion sequencing (Tn-seq), combined with metabolic modeling and live imaging, to study how P. aeruginosa adapts to colonize the mucosal surface of the lung and tolerate antibiotic treatment,” says Lucas Meirelles, who led the study.

Thanks to the Tn-seq technique, the scientists identified which genes were important for the bacterium’s survival under different conditions: those which contributed to fitness during mucosal colonization and those which helped the bacteria tolerate antibiotics.

The scientists also used computational modeling to simulate how the bacteria metabolize nutrients in the lung environment, which helped pinpoint the exact metabolic pathways P. aeruginosa relies on during infection.

Finding the right balance

The study found that P. aeruginosa adapts to the lung’s mucus by relying on sugars and lactate, nutrients that are abundant in infected lungs. However, to survive on the mucus, the bacterium also needs to synthesize essential but less available nutrients, like amino acids. This self-sufficiency, or “metabolic independence”, helps the bacterium thrive in the early stages of lung infection.

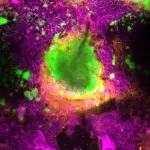

What Persat's team uncovered is the mechanism behind this dilemma. They found that biofilm formation imposes a “metabolic burden,” meaning that producing the sticky matrix that holds the biofilm together consumes resources, slowing down the bacteria’s ability to spread. In experiments, bacteria that couldn’t form biofilms spread more efficiently but were left vulnerable to antibiotics. This new insight into the metabolic costs of biofilm formation explains how the bacterium balances growth and antibiotic tolerance.

The study highlights the delicate balancing act that Pseudomonas aeruginosa must perform during infections. While the bacteria need to colonize the lung effectively, their best survival strategy – forming biofilms – limits their access to nutrients and, therefore, their ability to spread. However, once antibiotics are introduced, biofilm formation becomes advantageous, protecting the bacteria from being wiped out.

Exploring new paths

The discovery opens the door for the exploration of new treatment strategies: if we can find a way to disrupt the bacteria’s ability to form biofilms without giving them more room to spread, it could make them more vulnerable to existing treatments. And therapies that target the bacteria’s metabolic pathways may also prove to be effective at weakening Pseudomonas infections.

More broadly, the scientists believe that studying pathogens like P. aeruginosa in infection models that replicate the physiology of human tissues is crucial for combating antibiotic resistance.

“Antibiotic resistance is set to become one of the most serious healthcare challenges of this century, and P. aeruginosa is a major contributor to this issue,” says Meirelles. “By using tissue-engineering to replicate the airway environment in the lab, we aim to better understand the physiology of this pathogen. Our hope is that this will uncover previously unknown targets to help us combat these infections and address antibiotic resistance.”

Other contributors

EPFL Laboratory of Computational Systems Biotechnology

Reference

Lucas A. Meirelles, Evangelia Vayena, Auriane Debache, Eric Schmidt, Tamara Rossy, Tania Distler, Vassily Hatzimanikatis, Alexandre Persat. Pseudomonas aeruginosa faces a fitness trade-off between mucosal colonization and antibiotic tolerance during airway infections. Nature Microbiology 25 October 2024. DOI: 10.1038/s41564-024-01842-3

END

University of Oxford researchers have made a significant step towards realising miniature, soft batteries for use in a variety of biomedical applications, including the defibrillation and pacing of heart tissues. The work has been published today in the journal Nature Chemical Engineering.

The development of tiny smart devices, smaller than a few cubic millimeters, demands equally small power sources. For minimally invasive biomedical devices that interact with biological tissues, these power sources must be fabricated from soft materials. Ideally, these should ...

FINDINGS

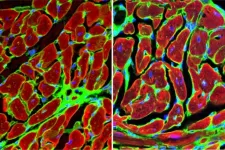

UCLA scientists have identified the protein GPNMB as a critical regulator in the heart’s healing process after a heart attack.

Using animal models, they demonstrate that bone marrow-derived immune cells called macrophages secrete GPNMB, which binds to the receptor GPR39, promoting heart repair. These findings offer a new understanding of how the heart heals itself and could lead to new treatments aimed at improving heart function and preventing the progression to heart failure.

BACKGROUND

Every 40 seconds, ...

News coverage of the 2024 election season has often centered on how partisan division has affected our politics. But a new analysis shows that political polarization also poses significant health risks—by obstructing the implementation of legislation and policies aimed at keeping Americans healthy, by discouraging individual action to address health needs, such as getting a flu shot, and by boosting the spread of misinformation that can reduce trust in health professionals.

“Compared to other high-income countries, the United States has a disadvantage when it comes to the health of its citizens,” ...

**EMBARGOED FOR RELEASE UNTIL OCT. 25 AT 5 A.M. ET**

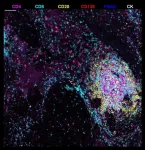

A newly described stage of a lymph node-like structure seen in liver tumors after presurgical immunotherapy may be vital to successfully treating patients with hepatocellular carcinoma, according to a study by researchers from the Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center.

The study, published Oct. 25 in Nature Immunology, provides new information about lymph node-like structures called tertiary lymphoid structures. These structures, which are highly organized ...

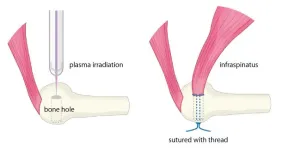

The human body, filled with muscles and moving parts, is far from indestructible. Injuries are common, especially where tendons and bones connect. In Japan, rotator cuff tears affect approximately 1 in 4 people over age 50, and reports state that even after surgery, about 20% of cases result in re-tears. To combat this, new healing methods to bolster current clinical practices are needed.

Graduate student Katsumasa Nakazawa, Associate Professor Hiromitsu Toyoda, and then Professor Hiroaki Nakamura at Osaka Metropolitan University’s ...

San Diego, CA (October 24, 2024) — Investigators recently uncovered key insights into newly defined rejection entities in kidney transplantation that may offer improved patient risk categorization post-transplant. The research will be presented at ASN Kidney Week 2024 October 23– 27.

Kidney transplant rejection continues to threaten the long-term success of kidney transplants, with microvascular inflammation (inflammation within capillaries) playing a pivotal role in graft failure. Due to its complex nature, this inflammation poses a major challenge in clinical practice. In response, the international Banff classification—the ...

**Embargo: 23.30 [UK time] / 06.30pm [US ET] Thursday 24th October 2024**

Peer reviewed / Literature review, systematic review and meta-analysis, opinion / People

Embargoed access to the Commission report and contact details for authors are available in Notes to Editors at the end of the release.

The Lancet Public Health: New Commission calls for regulatory reform to tackle the health impacts of the rapid global expansion of commercial gambling

Gambling harms are far more substantial than previously understood, exacerbated by rapid global expansion ...

Barcelona, Spain: Researchers have shown that they can accurately re-create clinical trials of new treatments using ‘digital twins’ of real cancer patients. The technology, called FarrSight®-Twin, which is based on algorithms used by astrophysicists to discover black holes, will be presented today (Friday) at the 36th EORTC-NCI-AACR [1] Symposium on Molecular Targets and Cancer Therapeutics in Barcelona, Spain.

The researchers say that this approach could be used by cancer ...

Barcelona, Spain: Researchers have shown for the first time that it is possible for a specially-designed ‘mini-protein’ to deliver a radiation dose directly to tumour cells expressing a protein on their cell surfaces called Nectin-4, which is often found in a number of different cancers.

In a study presented on Friday at the 36th EORTC-NCI-AACR [1] Symposium on Molecular Targets and Cancer Therapeutics in Barcelona, Spain, Mike Sathekge, Professor and Head of the Nuclear Medicine Department at the University of Pretoria ...

Barcelona, Spain: Patients with advanced bladder cancer that had spread to other parts of the body (metastasised) have responded well in a phase I clinical trial of an investigational drug, TYRA-300. The drug targets changes in the FGFR3 gene that drive tumour growth in about 10%-20% of these patients.

Associate Professor, Ben Tran, a medical oncologist at Peter McCallum Cancer Centre in Melbourne, Australia, presented the first results as of 15 August 2024 from 41 patients enrolled in the SURF301 study in a late-breaking oral presentation at the 36th EORTC-NCI-AACR [1] Symposium on Molecular Targets and Cancer Therapeutics ...